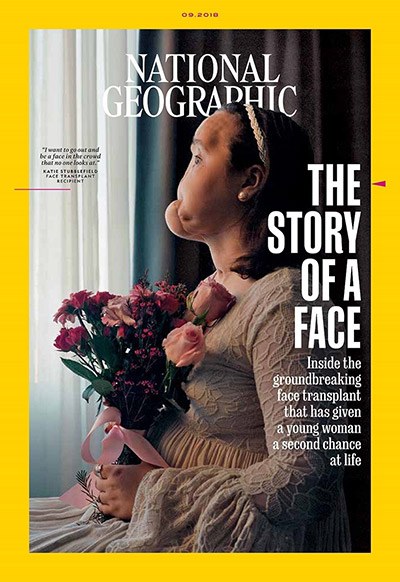

Behind the Scenes: National Geographic’s Story of a Face Transplant

A young woman’s life-changing face transplant surgery at Cleveland Clinic, the subject of National Geographic’s September cover story, made headlines around the world.

The story details the remarkable journey of Katie Stubblefield, who attempted suicide at 18 and received a second chance at a normal life through a face transplant at 21. The story was a nearly three-year undertaking by writer Joanna Connors, photographers Maggie Steber and Lynn Johnson, and others at National Geographic. Throughout the project, they had unprecedented access to Katie’s family, medical team and clinical areas.

Now, more than a year and a half after the May 2017 surgery, Katie says she feels whole again. She has achieved her goal – to be able to go out in a crowd and not be seen “as some kind of monster.”

How the story began

The article’s genesis was a chance meeting between Toby Cosgrove, MD, then CEO and President of Cleveland Clinic, and Susan Goldberg, editor of National Geographic and former editor of Cleveland’s Plain Dealer. The meeting led to the idea of an article that would show how innovation, research and the work of a highly skilled medical team can dramatically improve a life.

Coincidentally, Cleveland Clinic’s face transplant team was about to begin working with Katie to do their third transplant.

Surgeons Frank Papay, MD, and Maria Siemionow, MD, approached the family to seek their interest and approval. The Stubblefields readily agreed, in hopes of educating and encouraging others.

When Ms. Connors was asked to write the article, she was told that National Geographic editors “wanted it to be more than medicine and science,” she says. “They wanted a human-interest story, and I knew I’d be spending a lot of time with the family. Katie really wanted to do it, and that made it easier.”

As a full-time writer for The Plain Dealer, Ms. Connors dedicated her nights, weekends and vacation days to numerous interviews and intensive research for the story.“ One year was spent getting to know the Stubblefields,” she says.

In conducting background research, “I read a lot of medical journals,” she says, noting that it reminded her of her childhood, when her father was managing editor of JAMA®, the Journal of the American Medical Association. “He would bring home the issues, and I loved looking through them.”

She and her colleagues were given an unusual opportunity to observe the medical team’s transplant practice sessions leading up to the surgery, as well as be in the operating room for Katie’s 31-hour procedure with over 100 Cleveland Clinic caregivers involved in Katie’s journey.

What made Katie’s story special

“This is really not just one story but multiple, hard-hitting stories,” says Dr. Papay, Chair of the Dermatology & Plastic Surgery Institute. “It’s about the incidence of teenage suicide attempts, the story of a beautiful girl coming back into society, of being the youngest face transplant patient ever, and how the family, despite all of the terrible things that happened, is probably the most amazing family I have ever met. And the last part is the technical aspect, bringing a team together and getting it charged up for a complex surgery.”

Having journalists following the team was a new experience, he says. “At first it was a little strange, but after a while, we got used to it because the focus was on the patient.”

For him, the magazine article was impactful, not only because of the Stubblefields’ experience, but also that of the donor’s family members, who were interviewed about her struggles and eventual death from a drug overdose. “This was the first time I’ve ever seen a publication cover both the donor and recipient side of a face transplant,” Dr. Papay says.

Ms. Connors, who has written Plain Dealer articles and a book about her own traumatic story of being raped, says that “what affected me was watching the Stubblefields’ process of opening up and realizing that they were sharing their pain, and things that they wouldn’t necessarily have wanted people to know about. It helped me change how I deal with petty things, more so than thinking about my own trauma. This was trauma to that whole family. It showed how little we actually need, if we have the closeness of family.”

Dr. Papay says that his team has received numerous kudos from other medical professionals. While he says he is gratified by that, he also expresses concern that while Katie’s transplant surgery was covered by a research grant from the U.S. Department of Defense, that grant has since ended.

“Everybody congratulates us on the success of the surgery, but the day goes on. We have more work to do, more patients to help,” he says. “We have been applying feverishly for grants, and we would love to have philanthropic support to advance our work.”

For Katie, the second chance she’s been given is very exciting, she says. “Life has been given back to me. I see how beautiful life is.”

Dr. Charis Eng Receives Highest Honor from American Cancer Society

At a special ceremony in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 18, Charis Eng, MD, PhD, was awarded the American Cancer Society’s Medal of Honor, its highest level of recognition. It was a career-defining moment for the internationally renowned genetics researcher, who says she knew from childhood what she wanted to do in life.

“When I was a young girl playing with my chemistry set and stethoscope, I never imagined this,” says Dr. Eng, Founding Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Genomic Medicine Institute. She also is the Sondra J. and Stephen R. Hardis Endowed Chair of Cancer Genomic Medicine and Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Personalized Genetic Healthcare.

“I am honored and humbled to receive the American Cancer Society’s Medal of Honor for Clinical Research,” Dr. Eng says. “To receive it on stage with the Hon. Joseph R. Biden Jr., Dr. Michael J. Thun, as well as Drs. Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier, the co-discoverers of CRISP-CAS9 gene editing, was overwhelming.”

Medal of Honor recipients embody the mission of the American Cancer Society, says Gary M. Reedy, the organization’s CEO. “We bestow this highest honor on these individuals for their significant contributions to the advancement and impact of our collective efforts to save more lives from cancer.”

Dr. Eng notes that her entire career has been devoted to understanding the genes that play a role in heritable cancers and translating those findings into improved patient care. “For example, our research led to the discovery of the relationship between certain germline (occurring in every cell of the body) PTEN mutations and Cowden syndrome, which carries high risks of breast, thyroid and other cancers. These discoveries were rapidly translated into everyday medical practice.

“We’ve since discovered other genes, as well, each of them bringing different cancer risks when mutated. Our work has characterized the age at cancer risk and the precise cancer risk associated with each gene over a lifetime, such that doctors can closely watch (enhanced surveillance) those who have gene mutations and catch the cancers when early and curable. Our work has broad implications for diagnosis, prognosis, therapy and prevention, forming the basis for precision oncology practice.”

In her award acceptance speech, Dr. Eng emphasized the importance of collaboration and teamwork through the years. “Like all such honors, it is not to an individual,” she said. “No, it is because of my research and clinical teams, past and present, and, might I say, future. It is because of my colleagues and collaborators. It is because of my mentors. It is equally to my parents, who supported me through thick and thin.”

She also thanked Cleveland Clinic and Serpil Erzurum, MD, Chair of the Lerner Research Institute, for providing “a wonderful work culture” that helped her achieve success, and she recounted how, early in her career, she submitted 10 grant applications to funding organizations, and only the American Cancer Society funded her work. “They gave me a Research Scholar Grant, and so I’m very grateful,” she said. “I’ve told people that without that grant, I would not be standing here tonight.”

Dr. Eng has published more than 500 peer-reviewed articles and was the principal investigator on projects totaling more than $50 million in research funding, including federal grants, multi-investigator grants and consortia, foundation funding and philanthropy. She has earned numerous honors, including the Doris Duke Distinguished Clinical Scientist Award, and was elected to the National Academy of Medicine, as well as the American Society for Clinical Investigation and Association of American Physicians.

Dr. Eng is a two-time VeloSano Pilot Award recipient, which provides seed funding for cancer research projects at Cleveland Clinic that have a high likelihood of leading to successful, future extramural grant funding. She also has received funds from the Center for Transformative Nanomedicine, a virtual center that prioritizes collaborative research projects from scientists at Cleveland Clinic and The Hebrew University.

In addition to her leadership at Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Eng has served on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health and Society.

Dr. Erzurum, who holds the Alfred Lerner Memorial Chair in Innovative Biomedical Research, praises Dr. Eng for significant contributions to her field.

“Charis is a true pioneer in cancer genomics, especially integrating the study of genetics into clinical care,” Dr. Erzurum says. “As a physician-scientist for over 20 years, she has dedicated her career to patient-oriented research in genetics and genomic medicine. She also has an unparalleled passion for mentoring the next generation of physician-scientists, PhDs, clinical researchers and healthcare leaders.”

Grant Supports Genetic Research in Atrial Fibrillation

It’s estimated that more than 6 million Americans may have atrial fibrillation (AFib), a heart rhythm abnormality that boosts the risk of stroke fivefold and doubles the odds of an early death. In at least 30 percent of these cases (and probably far more), patients are genetically predisposed to developing the condition. Scientists from Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute are leading the way in identifying significant genetic variations related to AFib and investigating potential therapies, lifestyle changes, and personalized treatments.

A multidisciplinary team from Cleveland Clinic recently published a study in the American Heart Association journal Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine that identified genes and genetic variations affecting the functioning of the heart’s left atrium — the top left chamber. Their research makes connections between gene variants known to raise AFib risk and mechanisms that may contribute to its development. The team also created an open, searchable database of genes that control the function of the heart’s left atrial appendage.

The study was led by Jonathan Smith, PhD, Mina Chung, MD, and David Van Wagoner, PhD. Dr. Smith is in Lerner Research Institute’s Department of Cellular and Molecular Medicine and holds the Geoffrey Gund Endowed Chair for Cardiovascular Research. Dr. Chung and Dr. Van Wagoner are in Lerner Research Institute’s Department of Molecular Cardiology, and Dr. Chung also has an appointment in the Sydell and Arnold Miller Family Heart & Vascular Institute.

In addition to Dr. Smith’s endowed chair support, the study was partially funded by a $1 million grant from Geoffrey Gund, President of the George Gund Foundation, as well as the Tomsich Atrial Fibrillation research fund and other philanthropic gifts.

“Understanding what specific genes do in relation to atrial fibrillation is one question we’ve been able to investigate with the Gund grant,” Dr. Smith says. “It allows us to be more proactive in pursuing questions that come up in our ongoing research. Our new research builds on it.”

The research team also recently was awarded a competitive $3.7 million, four-year grant by the American Heart Association to focus on three new areas: how aging and metabolism interact with specific genes to cause AFib; whether lifestyle changes, with or without the drug metformin, can slow progression; and a deeper look at subtypes that could lead to personalized treatments. Philanthropic support through Cleveland Clinic’s Center of Excellence in Translational Functional Genomics, directed by Dr. Chung, helped advance the researchers’ work, which led to their securing the AHA grant.

Helping Cancer Patients Feel Normal Again

“I just had this feeling, from the time my doctor first found the lump,” Lia Augoustidis says emphatically. “I told my husband, I just have this feeling that its cancer.”

Lia tells her story freely, her voice warm and strong. “At the mammogram, they had me wait because they wanted to take more pictures. And then more pictures. As soon as the radiologist walked in, she patted my leg. I was like, OK, it’s cancer. No one just walks in and touches your leg like that. Then she introduced herself and told me to call her by her first name. Now I know it’s cancer because who tells you to call them by their first name if it’s not?” she says, laughing.

How Could This Happen?

In October 2017, Lia had recently finished breastfeeding her third child and was at her gynecologist’s office for her annual check-up. Not yet 40, she hadn’t had a mammogram and recalls joking about it with her doctor during her exam. “It was a minute later when she felt a small lump,” Lia recalls.

Eleven days after the pathology report confirmed the breast cancer diagnosis, Lia had surgery to remove a small tumor. A slight amount had metastasized to her lymph nodes.

Because of her work in the medical industry, Lia knew that with early detection and diagnosis of breast cancer is treatable and highly curable. “I also knew that I hadn’t done anything to cause it — I’m not obese, I work out, I eat healthy food, I breastfed all my children, no one in my family has ever had breast cancer, and I don’t have the BRCA gene. I wasn’t mad at myself, I was frustrated. How could this happen? Why did this happen?”

Chemo is Tough

As a working mom of three children ages 7, 4 and 1, Lia didn’t have time to feel sorry for herself. She was tired, sore, emotional and frequently in tears. Her chemotherapy started Dec. 1, with six treatments every three weeks through March. “It was tough,” she admits.

René Barrat-Gordon, LISW-S, a social worker at Cleveland Clinic’s Taussig Cancer Center, had connected with Lia shortly after her diagnosis. “My role is to get to know each patient, first on the phone and then in person,” she says. “The goal is to establish a relationship and find out what kinds of tools could be beneficial — tools that help people feel better about themselves when they’re facing a cancer diagnosis.”

René says one of the best resources is the cancer center’s Patient Support Services, which include services and programs such as massage, yoga classes, and music and art therapy. These services are not covered by insurance and are supported through philanthropic contributions.

René encouraged Lia to investigate the Reflections Wellness Program, a complementary wellness program that offers a variety of services to patients, including facials, makeup tutorials, and oncology massage, to help her cope with the stress and anxiety.

Knowing the side effects of chemo, Lia first visited the Wig Boutique, which provides wigs, hats, and other accessories at no charge to Cleveland Clinic cancer patients who are undergoing treatment. She used a cooling cap to try to prevent hair loss during chemo but chose a wig just in case. “My 4-year old was really into princesses, and there aren’t any princesses with short hair — or no hair.” She estimates she lost about 60 percent of her long hair but was able to style it and not use the wig, which she’ll now donate to another cancer patient in need.

Lia says the massages and facials are her favorites because the caregivers know how to work with someone who’s in treatment for cancer. “During a massage, there are certain positions I can’t lie in comfortably. The masseuse knows this and knows what to avoid.”

Cleveland Clinic held its annual benefit for patient services Oct. 12 at The Madison in Cleveland. “The Social: An Evening of Hope” paid tribute to individuals and businesses whose tireless commitment and generosity make critical patient services possible for Cleveland Clinic cancer patients. The free services go beyond medical needs, addressing the emotional, mental and financial needs of patients. In that very same spirit of hope, guests of the evening enjoyed a special presentation and tribute, food and beverage pairing stations, and the boutique-style Hope Shop. 100% of the evening's proceeds benefit critical patient services for Cleveland Clinic cancer patients.

Finding Ways to Feel Normal Again

Lia is appreciative of the free services because she rarely splurges on massages and facials. With her typical sense of blunt humor, she says they’re a nice way to feel normal again. “I’m a woman who had her breast cut off, I’m starting to go bald, I’ve got patches of hair, my eyebrows are falling out, my face is starting to look different … it’s just nice to go somewhere and feel like a woman again — to have that sense of femininity back, even if just for a little bit.”

Lia is finished with chemo but still needs reconstructive surgery, slated for January, and five to 10 years of endocrine therapy. Her type of cancer has a high rate of recurrence. “I’ve learned that tomorrow isn’t a given,” she says quietly.

René is grateful to the compassionate donors who support the complementary services and says they help cancer patients in so many ways. “You give them pride in how they look, how they feel, how they relax. You help people look outside the cancer ‘box’ by listening to music or creating art or getting a massage. The fact that somebody from outside is contributing to their well-being really makes patients feel special,” she says, adding that some patients cry when they learn the services are free. “They’re so touched and so appreciative. Your help makes them feel special.”

How Can You Help

Cleveland Clinic’s Patient Support Services are made possible through the generous contributions from donors like you. Your gift has an impact on the lives of cancer patients in so many ways.