From Lifesaving Surgery to Philanthropy: A Testament to Cleveland Clinic's Impact

Ask Gene Larson what Cleveland Clinic means to him, and he’ll mince no words: “The Cleveland Clinic means life, itself.”

In fact, that’s true for two generations of Larsons: Gene, who underwent lifesaving heart surgery at Cleveland Clinic in 2011, and his father, who was rushed there by car, in 1949, from a small hospital in a coal-mining town in Pennsylvania.

“My dad was critically ill with ulcerative colitis,” Gene, 80, recalls. “My uncle took him out of the Pennsylvania hospital and drove him to Cleveland Clinic.

“And the doctors at Cleveland Clinic saved his life.”

It was a dramatic introduction to Cleveland Clinic’s world-class care, and one that forged a lifelong relationship between the man and the institution.

Indeed, Gene’s association with Cleveland Clinic also put him on a remarkable career path, one that saw him grow from young metallurgic engineer to a true pioneer in the field of medical ultrasound. Encouraged by a Cleveland Clinic physician seeking better diagnostic alternatives, Gene eventually went on to found five, and lead six, medical device and industrial technology companies; among his other career accomplishments, he holds nine medical device and drug delivery patents.

But Cleveland Clinic’s most powerful impact on Gene came later in life, when he discovered he had congenital heart disease.

During the 1980s, Gene and his wife, Peg, moved from Pennsylvania to Washington state, but they regularly returned to Cleveland Clinic for healthcare. Eventually, Gene’s heart condition was determined to be critical, and he underwent cardiac surgery at Cleveland Clinic in 2011.

Lars G. Svensson, MD, PhD, Chair of the Sydell and Arnold Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute, was Gene’s surgeon. “It was fairly extensive surgery,” Gene explains, perhaps with a bit of understatement. “I had aortic disease, so it involved repairing my aorta and replacing my aortic valve.”

The outcome, however, was excellent. “In fact, afterward I went on to start another company (Echo Ultrasonics, in Bellingham, Washington) because I felt 20 – maybe 30! – years younger!”

Meantime Peg, now 79, had also become a patient at Cleveland Clinic, where she was successfully treated for osteoporosis and elevated blood pressure. “On my last visit,” Peg says, “they also detected a heart murmur, so I will also continue to be seen in the Heart Institute.”

The couple’s healthy lifestyle has been a plus. “We’ve been on the Mediterranean Diet for 50 or 60 years – before it was even called the Mediterranean Diet,” says Peg. “We choose organic foods, we watch our weight carefully, and over the years we kayaked, rode bikes and were runners for 20 years.” While running was recently replaced by what Peg calls “aggressive” daily walking, their commitment to good health remains strong.

No surprise then that both Gene and Peg continue their full-time roles at Echo Ultrasonics, where they are joined by their daughters, Marian and Emily. (A third daughter, Kathy, is a business owner in San Diego.)

"I believe we have a responsibility to ourselves to do everything we can to optimize our lives,” says Gene. “Getting the best possible medical intervention is part of the story, of course. But I think the onus is on us to help our bodies do the best they can throughout our lives.”

As part of that commitment, Gene and Peg continue to make annual trips back to Cleveland, for ongoing healthcare, from their island home off the coast of Washington. “For the world-class care that we receive at the Cleveland Clinic,” says Gene, “we think it’s worth the travel.”

While Gene’s story may be unique, he feels strongly that the care he and his family have received at Cleveland Clinic is not. That’s why both Gene and Peg are confident in recommending the healthcare organization to others. “I have received outstanding care at the Cleveland Clinic, because that’s what the Cleveland Clinic delivers,” Gene says. “And when Peg and I recommend Cleveland Clinic to people, we know they will get the best care, too – just as we did. That’s the marvel of the Cleveland Clinic!”

Looking back at his 75-year relationship with Cleveland Clinic, Gene is clear-eyed about its importance. “For me – and for my father – Cleveland Clinic has meant life itself.

“Starting as a very young boy, I was able to see its unique, integrated clinical practice model in action, and it has become what I consider the gold standard for healthcare,” he says.

In turn, it has ignited a passion to give back for all he’s received. “The outstanding medical care that saved both my father and me has been a true gift,” Gene says. “That’s something we want to pay back.”

To that end, Gene and Peg are passionate supporters of Cleveland Clinic, launching an endowment in cardiac surgery research that will be their legacy. As part of their commitment, they have also taken the time to impart the value of philanthropy to their children. “We think Norma Lerner (chair and president of the Lerner Foundation) had great advice: It’s up to us as parents to help our children understand the tremendous impact that philanthropy can have – especially in healthcare and especially at the Cleveland Clinic.”

Gene and Peg also maintain a deep and abiding admiration for Dr. Svensson and the research he pursues.

“We admire Dr. Svensson for the man, for the surgeon and physician, and for the leader he is,” says Gene. “He believes that a world-class institution needs to be doing world-class research, and his achievements have impacted cardiac care throughout the world. His work has been a guiding principle for us, and for our philanthropic support for the Cleveland Clinic.”

As donors, the Larsons feel their support – and what can be accomplished with it – is truly valued.

“I think when we look back on our lives, we hope to see we’ve left some footprints behind,” Gene says.

“After all, when you’ve been given a gift of great value, as we have, you are naturally very appreciative to the giver,” Peg adds. “And the healthcare we have received from the Cleveland Clinic has been a marvelous gift.”

There’s just no question about it, Gene says. “It’s Cleveland Clinic that we want to support.”

Imaging the Future

“Heart disease takes 20 years to manifest itself, and by then it can be too late,” says Christopher Nguyen, PhD. “With the right imaging, we can see the cracks in the building before the building falls.”

In May 2022, Dr. Nguyen became the inaugural director of Cleveland Clinic’s first Cardiovascular Innovation Research Center (CIRC), a unique vehicle for researchers to empower clinicians with the technologies to better understand, predict and treat cardiac disease. One year later, he helped secure the acquisition of an MRI scanner that is five times stronger than any other clinical scanner in the world. Equipped with technology that can only be found at Cleveland Clinic, he and his research team are picking up speed in their mission to develop insights that matter in the clinic.

The First Breakthrough

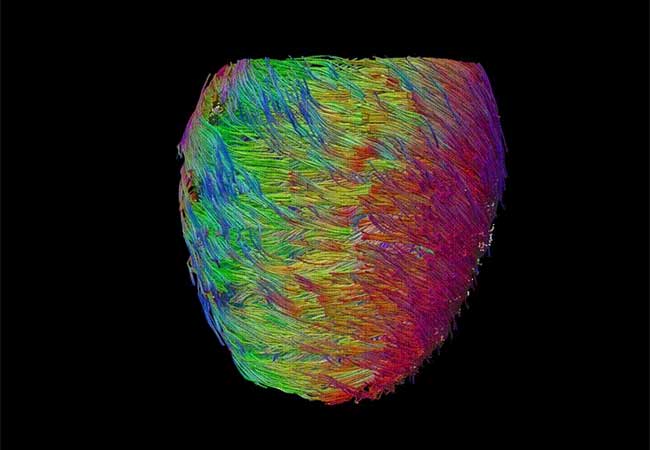

A pioneer in cardiac MRI, Dr. Nguyen made waves in the field while earning a PhD in biomedical engineering at the University of California Los Angeles. At an improbably young age, he discovered a new technique for imaging the heart with more precision than ever before. MRI technology had long been used to evaluate the structure of brain tissue, but evaluating the structure of the heart is a far more difficult task given its constant movement. Dr. Nguyen developed a technique called second order motion compensation (M2) to adapt MRI technology for the heart, revealing micro-level information about the organ’s fibers.

His achievements caught the attention of teams at Harvard and MIT, who recruited him to join their efforts to develop cardiac imaging techniques with clinical applications.

“I realized this new MRI technology gave us keys to the kingdom,” says Dr. Nguyen. “Not only could we create a detailed portrait of what a healthy heart should look like, but we could also view disease on a micro level.” By manipulating the three components of the MRI machine—the magnetic field, radiofrequency, and gradients—in different ways, he learned how to answer specific questions about different patients being scanned. In the case of heart failure, for example, cardiac MRI can tell researchers exactly which cells in the heart are damaged and what is damaging them.

“Gradually, I expanded my focus from developing novel imaging techniques to understanding the disease processes that are revealed by those techniques,” Dr. Nguyen said.

The information gleaned from cardiac MRI can inform the development of custom-made valves, implantable devices, and heart models that allow physicians to plan and practice surgeries ahead of time, improving patient outcomes while minimizing time in the OR. By revealing that the cells of the heart are arranged in an intricate double helix structure, for example, Dr. Nguyen’s M2 technique paved the way for a rapid leap in the effectiveness of artificial hearts—from 30% to 80%, by some accounts.

The Big Move

Dr. Nguyen’s star was rising quickly in Boston as he became the top-funded researcher in the cardiac MRI space, but he was missing a crucial ingredient to make further progress: a patient population.

“As exciting as my work was, it was only informed by data from a handful of patients,” he says. “To truly prove the validity of a new technology or technique, you need to prove it works for thousands of patients. Cleveland Clinic is ranked No. 1 in the nation for cardiology for a reason. In terms of infrastructure and patient volume, it provided a unique opportunity to rapidly prove that something works and put it to use.”

Dr. Nguyen launched the CIRC and recruited an accomplished team of 30 researchers to advance imaging-based innovations in collaboration with leading cardiologists at the Sydell and Arnold Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute (HVTI). In April 2023, he secured a one-of-a-kind MRI scanner from Siemens and persuaded the company to send its own scientists to join the CIRC.

In MRI technology, the gradient enables a process called encoding, which records the strength of the magnetic field at different points of the scanner. The stronger the gradient, the faster the researcher can encode information and form a precise image. The new MRI scanner has an overall gradient five times stronger than any other machine in existence.

The remarkable power of the new scanner provides three major advantages to Dr. Nguyen and his team. First, it significantly expedites the imaging process. A 90-minute cardiac scan with existing MRI technology becomes a less than 20-minute scan with the new scanner. Second, it allows researchers to view the heart in more frames per second, revealing subtle defects in motion or structure that might not otherwise be detected. Third, it brings researchers closer to imaging the heart at a cellular level. Previously, they were viewing the heart on an order of 1-10mm, or 1,000-10,000 microns (For reference, the width of a hair is approximately 10 microns). Now, they can reconstruct the heart on an order of 100 micron or less, which is more than 100 times smaller than the smallest structures they could previously see. This massive leap in imaging capability further improves their ability to understand the mechanisms of disease.

Combined with artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning techniques, the new MRI scanner will provide a more targeted map of where, how and when to intervene when something goes wrong in the heart. A PhD student under Dr. Nguyen’s supervision recently demonstrated the ability to use cardiac MRI to create a realistic “digital twin,” which allows researchers like him to look into the future and predict which parts of the heart will be damaged after a given length of time.

“This is where precision medicine comes in,” says Dr. Nguyen. “We aim to use the data we’re collecting to do things like decide between two classes of drugs based on that patient’s specific subtype of disease, or build a tailor-made device.” In the near future, he believes, cardiac MRI can give a surgeon the ability to 3D-print a valve that is fitted to a specific patient. With a custom valve rather than a pick of three sizes, the patient will experience a lower risk of leakage and other complications.

The Next Frontier

Dr. Nguyen and his team have scanned 200 patients on the new MRI scanner, and they hope to scan 1,500 patients over the next year. The value of the information they derive, he says, hinges on their ability to use automated CMR (AutoCMR), a technique that leverages AI to assess cardiac function from MRI images rather than requiring manual analysis. This technique would enable more consistent creation of the heart’s digital twin, bringing leading-edge innovation directly into the clinic.

“To implement AutoCMR and make our technology cheaper and more accessible, philanthropy has to play a role,” says Dr. Nguyen. “We aim to someday scan as many as 100,000 patients a year—that's the same number of MRI scans performed in the UK every year, and we can do it all in our own hospital system.”

But right now, he and his team only use 3% of the MRI scanners that are available to them at the Cleveland Clinic because conventional clinical CMR is so complex to perform and slow to interpret.

“AutoCMR can solve all of these challenges while also enabling powerful next-generation technology,” Nguyen says. To scan more patients and bring their results into the clinic, he explains, he and his team need to expand the numbers of students, postdocs, and professional scientists among their ranks.

“We are listening to what doctors need and using their insights to develop solutions for their patients, but it will take a major investment of time and resources to get our technologies across the finish line and into industry,” Dr. Nguyen says. “Traditional federal funding cannot get us there. Only the generosity of philanthropy can bring real change. We’re just getting started.”

To help Dr. Nguyen expand his team and continue to push the boundaries of cardiac MRI, please make a gift today.