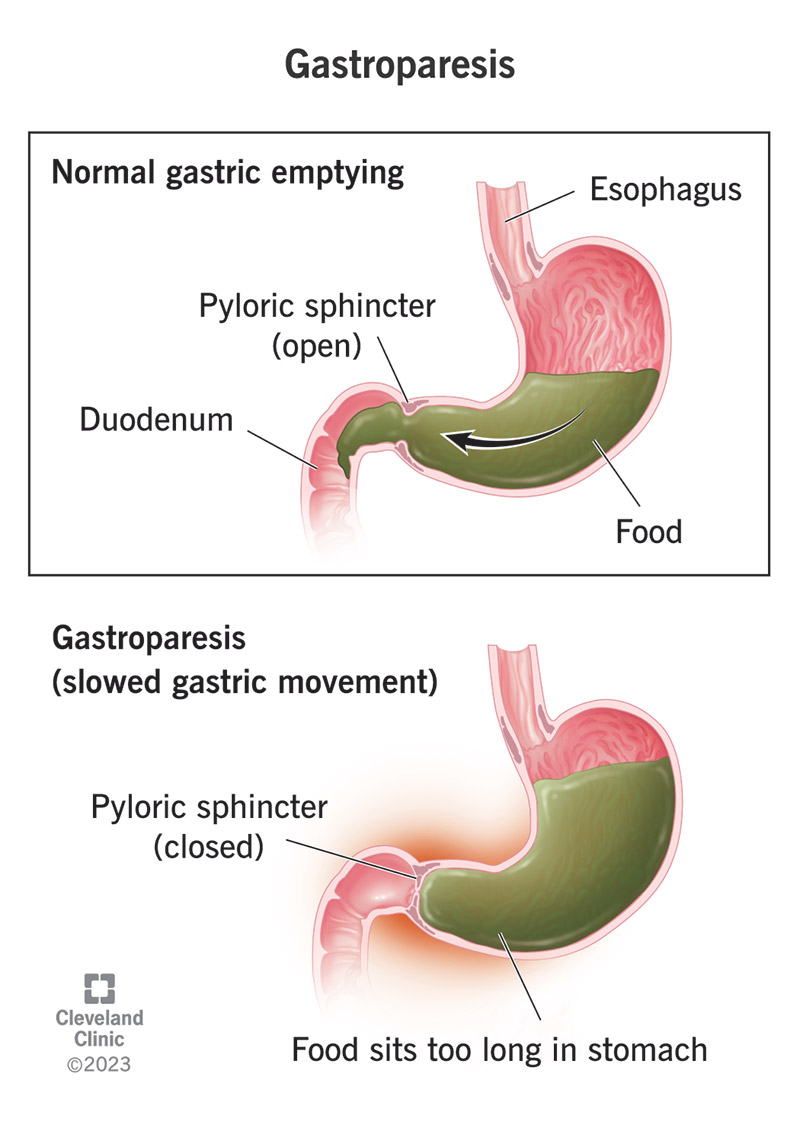

Gastroparesis means paralysis of the stomach. It’s a functional disorder affecting your stomach nerves and muscles. It makes your stomach muscle contractions weaker and slower than they need to be to digest your food and pass it on to your intestines. This leads to food sitting too long in your stomach.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Gastroparesis, which means stomach paralysis, is a condition affecting the nerves and muscles in your stomach. It interferes with the muscle activity (peristalsis) that moves food through your stomach and into your small intestine. When your stomach muscles and nerves can’t activate correctly, your stomach can’t process food or empty itself like it should. This holds up your whole digestive process.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

People with gastroparesis have uncomfortable symptoms during digestion, and they can also have longer-lasting side effects. They might have low appetite and trouble meeting their nutritional needs, or trouble controlling their blood sugar. When food does finally pass from the stomach, it may not pass completely and may leave some behind. This can develop into a hardened, solid mass called a bezoar.

Healthcare providers often classify gastroparesis into sub-types based on what’s causing it. For example, gastroparesis that occurs as a side effect of diabetes may be called diabetes-related gastroparesis. Gastroparesis that occurs as a complication of surgery may be called post-surgical gastroparesis. Gastroparesis that occurs for no identifiable reason is labeled as idiopathic gastroparesis.

Most gastroparesis cases (between a quarter and a half) are labeled as idiopathic, which means healthcare providers couldn’t determine the cause. But cases falling into this subtype may be from a variety of causes, including known causes that just couldn’t be determined. Diabetes is the most common single cause of gastroparesis. Around one-third of cases are diagnosed as diabetes-related.

Common symptoms include:

Advertisement

When your stomach muscles aren’t working right, food sits in your stomach for a long time after you eat it. You may feel full almost immediately and for a long time after eating. You may have a stomachache, feel nauseous or throw up. Your stomach may feel bloated or distended (stretched) and you may have acid reflux as a side effect. When stomach acid backwashes into your esophagus, it can feel like heartburn.

Gastroparesis symptoms vary between people. A small subset of people report persistent stomach pain that interferes with their daily life. But how much pain people feel doesn’t appear to be connected to how severe their gastroparesis is, or how slowly their stomach empties. Some people may feel more pain because their nerves are more sensitized. This may be related to the cause of their gastroparesis.

Gastroparesis slows down your whole digestive process, which can delay your bowel movements. It can also deliver large, undigested pieces of food to your intestines, which are more difficult to pass through. While gastroparesis doesn’t directly affect muscle movements in your intestines, some conditions that cause it can. So some people experience gastroparesis and constipation at the same time.

Damage to the nerves that activate your stomach muscles is the main cause of gastroparesis. Less commonly, it’s the muscles themselves that are damaged. The overall result is that the muscle contractions that churn food in your stomach and then squeeze it out through the bottom are impaired. This leads to indigestion and delayed gastric emptying — food sitting too long in your stomach.

Known causes include:

Around one-third of people with diabetes (Type 1 or Type 2) develop gastroparesis. Diabetes-related gastroparesis is a type of diabetes-related neuropathy. It happens when high blood sugar levels damage your nerves. High blood sugar levels also damage the blood vessels that carry oxygen to your tissues, so your stomach nerves and muscles are both affected.

Surgery on or near your stomach can injure the vagus nerve that runs through your stomach and coordinates its movements. Post-surgical gastroparesis can develop any time after surgery. Sometimes it happens right away, but it can also develop months (or even years) later. Common surgical procedures that have caused post-surgical gastroparesis include:

Advertisement

Gastrointestinal infections can trigger gastroparesis. Viral infections such as norovirus and rotavirus are more common causes, but bacterial infections can cause it too. Scientists aren’t sure whether it’s the infections themselves that damage your stomach nerves or if the immune cells meant to kill the infection damage your nerves by mistake.

In autoimmune disease, your immune system sends antibodies to attack your own body cells, mistaking them for an infection. New research indicates that these autoantibodies may damage the nerves in your stomach. You may have autoimmune gastroparesis even if you have no other symptoms of autoimmune disease, or if your other symptoms are unrelated to your stomach.

Certain medications and recreational drugs can block the nerve signals that activate your stomach muscles. This can lead to temporary gastroparesis. Some of these medications are prescribed for conditions also linked to gastroparesis, such as diabetes. If you already have gastroparesis, or you’ve had it before, these are medications to avoid. They include:

Advertisement

Less common causes of gastroparesis include:

Complications of gastroparesis can include:

Chronic nausea and vomiting, or simply the loss of appetite, can lead to weight loss and malnutrition. If you vomit frequently, it can also lead to dehydration and electrolyte deficiencies. You may need to recover in the hospital with nutritional therapy and fluid replacement.

Gastroparesis causes abdominal distension, which makes it easier for stomach acid to escape out of the top of your stomach into your esophagus. Chronic acid reflux can cause complications for your esophagus, such as heartburn and inflammation (esophagitis).

Advertisement

Gastroparesis interrupts the regular, controlled flow of food through your digestive system. This can also interrupt the regular, controlled release of glucose into your bloodstream. When food sits for too long in your stomach, your blood sugar may drop too low. When food finally releases, your blood sugar may spike. These fluctuations are especially complicated for people with diabetes, and they can make gastroparesis worse.

A bezoar is a compacted, hardened mass of food stuck in your stomach. It forms out of pieces that were left behind when your stomach emptied. A bezoar may become too big to pass through the outlet at the bottom of your stomach. It can also block it and make it hard for any other food to pass through. Healthcare providers treat bezoars with medication to dissolve it, or if necessary, surgery to remove it.

A healthcare provider will ask you about your symptoms and health history, including conditions and procedures that can cause gastroparesis. They’ll use imaging tests to look inside your stomach to make sure there’s nothing physically obstructing it, which might cause the same symptoms. If they don't find an obstruction, they’ll follow up with gastric motility tests, which evaluate your stomach muscle activity.

The first step is having imagining tests to rule out an obstruction as the cause of your symptoms. These tests could include:

If there is no physical obstruction, the next step would involve gastric emptying studies to measure your gastric motility. These could include:

If your GES test results are abnormal, your provider may recommend an electrogastrogram (EGG), which is a test that measures the electrical activity of your stomach muscles.

You may have additional tests to try to identify the cause of your gastroparesis. Your example, a blood test may discover antibodies from a prior infection or autoantibodies that indicate autoimmune disease.

Healthcare providers can’t directly fix the damage that causes gastroparesis, but they can offer treatment to stimulate muscle contractions in your stomach and encourage it to empty. Medications are the first-line treatment, with surgery reserved for those who don’t respond to medications or can’t take them. All of the treatments have potential side effects, and no one treatment works for everyone.

The goals of treatment are to:

Your treatment plan may include:

Prokinetics, medications that stimulate gastrointestinal motility, are the first-line treatment for gastroparesis. Prokinetics include:

Additional medications may include:

You might need to change your diet to accommodate your condition — for example, eat less fiber and less fat to make digestion easier. You might also need more specific nutritional therapy to replace missing nutrients. Your provider might prescribe dietary supplements, or even temporary tube feeding or IV feeding. Some people may need IV fluids to rehydrate and correct electrolyte imbalances.

Surgery is the last resort in gastroparesis treatment. If all other treatments fail, you might need surgery to modify your stomach to help food pass through it. Procedures to modify your stomach include:

Sometimes gastroparesis caused by short-term drug use or a short-term infection later goes away. For most people, gastroparesis is not curable, but it is manageable with treatment. It may take some trial and error to arrive at the treatment that works best for you, and there may be lingering symptoms or side effects of the treatment. Your healthcare provider can help you manage these when they flare up.

In general, gastroparesis isn’t life-threatening. Some of the possible complications of gastroparesis can be life-threatening if they’re very severe. These complications are related to malnutrition, dehydration, electrolyte imbalances and blood sugar fluctuations with diabetes. Your healthcare provider will work with you to minimize the risk of these complications. With appropriate care, the risk is very small.

Pay attention to your symptoms and what foods or habits make them better or worse. Small adjustments can make a real difference in how you feel. Some people find it helpful to:

Gastroparesis can be mild to severe, and so can its effect on your quality of life. While there’s no quick fix, there are many treatment options available to help you manage it. Your healthcare provider will work closely with you to find the treatment plan that works best for you. You may also find diet and lifestyle adjustments can help. Meanwhile, scientists continue to research new treatment approaches.

When you can’t eat a few bites without feeling full or throwing up, it’s time to get help. Cleveland Clinic experts can help diagnose and treat your gastroparesis.

Last reviewed on 02/12/2025.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.