Visceral hypersensitivity means that your threshold for pain in the internal organs is lower. It’s commonly associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders such as IBS. If you have visceral hypersensitivity, the normal functioning of your organs might cause you discomfort.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22997-visceral-hypersensitivity)

Visceral hypersensitivity refers to your experience of pain or discomfort in your visceral organs — the soft, internal organs that live in your chest, abdomen and pelvic cavity. If you have visceral hypersensitivity, your threshold for pain in these organs is lower than normal.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Healthcare providers have been able to measure the visceral pain threshold in certain patients with tests that apply small amounts of internal pressure to some of these organs. Most people don't experience discomfort from these tests, but those with visceral hypersensitivity do. They also may feel discomfort from the normal functioning of the organs that other people wouldn’t notice.

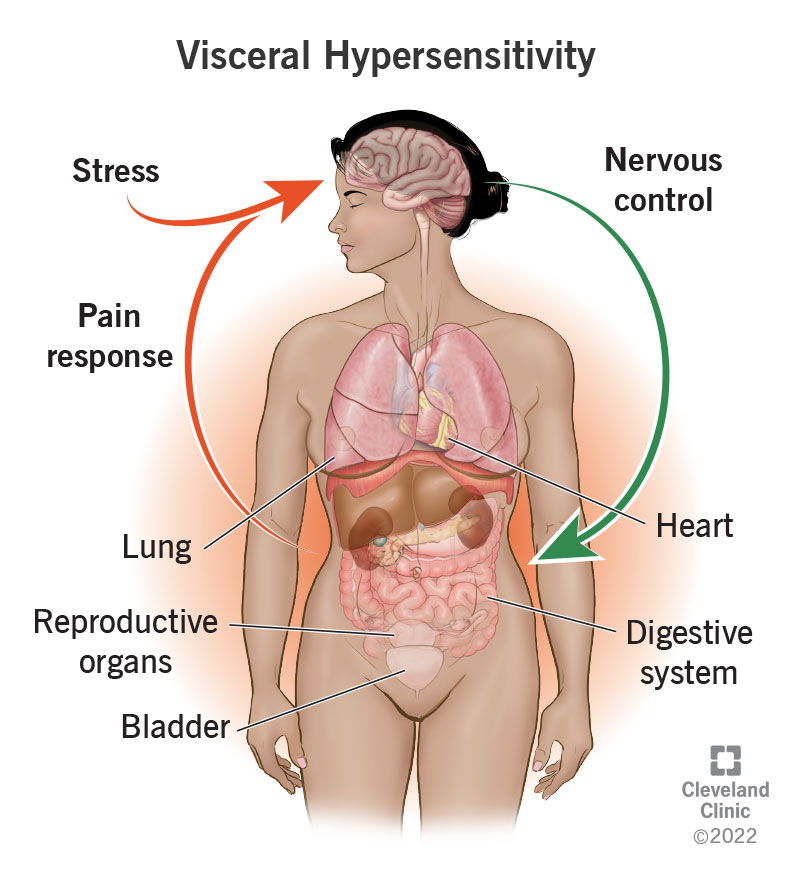

Your visceral organs include your heart and lungs, your bladder and reproductive organs and the organs in your digestive system. Visceral hypersensitivity (VH) can make the normal functioning of one or several of these organs feel uncomfortable. Many people with visceral hypersensitivity are also diagnosed with functional disorders, especially gastrointestinal ones.

Functional disorders cause pain and discomfort in the internal organs in response to normal amounts of internal pressure from gas, fluids or solids moving through. Healthcare providers believe that visceral sensitivity plays a role in how these functional disorders develop (their etiology).

It's not the same, but visceral hypersensitivity is often involved in IBS. People with IBS are the ones most often evaluated for visceral hypersensitivity. About 40% of them are diagnosed with VH. Healthcare providers believe that visceral hypersensitivity may result from and/or contribute to chronic IBS symptoms. It's also involved in other functional disorders, but most of the research on visceral hypersensitivity is related to IBS.

Advertisement

Visceral hypersensitivity is a relatively new diagnosis. We don’t know yet exactly how common it is. We do know that functional disorders are common. IBS alone affects at least 20% of the population, and up to 40% of people with IBS have visceral hypersensitivity. Considering how many other functional disorders may involve visceral hypersensitivity, it’s easy to estimate that VH affects at least 10% of the population.

Visceral hypersensitivity usually accompanies another functional disorder. However, not everyone with a functional disorder appears to have visceral hypersensitivity. It also has a significant overlap with stress-related mood disorders. And there is some evidence that it may run in families. VH is twice as common in women as it is in men.

You may be more likely to have visceral hypersensitivity if you have:

In language, the word “visceral” implies a deep-down, intuitive feeling, as in “a visceral reaction." It's also closely associated with your gut, as in a “gut feeling." Visceral pain has these qualities.

It feels diffused, or not as precisely located as somatic pain from an injury, even when it is intense. It often affects your gut, causing symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea and indigestion, even when the source of the pain is located elsewhere.

It also may feel closely tied to your emotional or mental state. Pain in the visceral organs can both trigger and be triggered by mental/emotional distress.

People with visceral hypersensitivity tend to feel chronic discomfort in their chest, tummy or lower organs. Chronic pain is defined as lasting consistently for more than three months. It may come and go, or it may be triggered by certain bodily functions, such as a full bladder or swallowing food. The organs affected may include your:

Visceral pain can be diffused or difficult to localize, and it can sometimes radiate somewhere else. This can make it tricky to pin down and diagnose. One telltale feature of visceral pain is that it may produce strong autonomic responses from your body, such as:

Advertisement

People with VH may also have other symptoms of functional gastrointestinal disorders. These disorders exhibit the same symptoms as inflammatory diseases, such as GERD, peptic ulcer disease and inflammatory bowel disease. The only difference is that with functional disorders, healthcare providers can’t detect any organic cause for them — no ulcers, no acid reflux, and no chronic inflammation.

Typical symptoms of functional GI disorders include:

Healthcare providers have also noted some less typical symptoms reported by people with IBS that may be related to visceral hypersensitivity. For example:

These symptoms suggest that, beyond simply physical irritants, the nervous system is involved.

Researchers are still working to understand exactly how visceral hypersensitivity develops. They speculate that the neurological response to pain may become overly sensitized by either severe or repeated exposure to physical, mental and/or emotional stress. Researchers have found several factors that may combine to lead to this response to pain. Some of these factors include:

Advertisement

Advertisement

When your nervous system has already been primed for a hyper-reactive pain response, visceral pain may begin either at the site of the organ or in the brain as a pathophysiologic response to stress. Healthcare providers have noted that visceral hypersensitivity often develops following a specific event. For example, an injury or infection or severe stress may have caused acute pain and inflammation in one of your organs. But after the emergency passed, your nerves continued to interpret normal sensations as pain and send those pain signals to your brain.

These nerves send pain signals to the part of your brain that registers pain, which signals to your brain regions that process the emotional part of the pain. An emotional response is part of your body’s way of teaching you to avoid whatever injured you. But this neural pathway also works in the reverse, where stress and emotions can enhance the perception of physical pain or irritation in the visceral organs. With visceral hypersensitivity, physical pain and emotional stress can constantly reinforce each other. Your brain responds to both with stress hormones, which make symptoms worse.

Your digestive system has its own nervous system, the enteric nervous system, which extends throughout the gastrointestinal tract. This is sometimes referred to as your “second brain” or the “brain in your gut." The enteric nervous system has nerve endings in every layer of the digestive organs. These nerve endings are activated by all kinds of things: digestive contents, bacteria and bacterial byproducts, stretch and distension, inflammation and chemical stress signals.

These nerves communicate discomfort to your brain, but they also signal your body to respond to the perceived threat in various ways: slowing or accelerating the digestive processes, purging out infectious agents and so on. If these nerves become chronically overexcited, they may perpetually trigger these kinds of responses, leading to symptoms of illness. Alternatively, VH may simply cause you to interpret normal gastrointestinal function as painful.

Although a variety of tests are used to diagnose VH in clinical studies, they aren’t normally given to patients seeking medical care. Visceral hypersensitivity is more often diagnosed the way other functional disorders are: by observing your symptoms and ruling out any structural causes for them. You’ll give a complete medical history and receive a complete exam before any standard tests are ordered. If these come back negative, you may be diagnosed with VH.

Researchers are still investigating new ways of targeting visceral hypersensitivity. Currently, treatment usually involves a combination of pharmaceutical and mind/body therapies. Since this condition equally involves your physical organs and your brain, approaching it from both sides is more pragmatic and has a better chance of long-term success.

Medications for VH are targeted to calm your nervous system. Typical pain medications don’t work for this type of pain. Heavy pain blockers like narcotics and opioids are not recommended because their side effects can make things worse. Instead, healthcare providers typically prescribe the same medications they would for psychological mood disorders such as anxiety and depression, only in much lower doses.

This isn't because they are presuming that you have mood disorders. Some people with VH do, but some don’t. If psychological symptoms are lowering your pain threshold, these medications will help raise that threshold. But they also help numb the pain signals from the nerves themselves. Treating the pain itself can help reduce stress hormones and put your body and brain in a better place to benefit from mind/body therapies.

Antidepressants include:

Other medications that may help with nerve pain include:

Medications can help treat your symptoms, but they don’t treat the underlying condition. That’s what mind/body therapies try to do. Taking advantage of neuroplasticity — the ability of your nervous system and brain to learn new patterns — these therapies attempt to stop nerve pain from initiating in the first place. Recommended therapies include:

These recommendations have not been thoroughly tested but have shown promise for helping to treat visceral hypersensitivity.

We don’t know. There have been inspiring reports of certain therapies significantly improving the condition for certain people. But this likely depends on many factors, including the original cause of their symptoms and how many other contributing factors are affecting their hypersensitivity. The good news is that research is ongoing and many promising avenues are being explored for targeting visceral hypersensitivity.

Diet is often recommended to help with IBS symptoms. If your visceral sensitivity occurs in your GI tract, diet may help by reducing the discomfort associated with poor digestion.

Digestion is not necessarily a component of visceral hypersensitivity. However, if you do have intolerances to certain foods, they could cause chronic low-grade inflammation, eroding your gut barrier, and over-feeding bad gut bacteria that feed on the carbohydrates that you can’t digest. All of these effects have been suggested as contributing causes of visceral hypersensitivity. In this case, the following diets might help:

Visceral hypersensitivity is a complex problem, and treating it requires a holistic approach. Healthcare providers increasingly recognize the importance of the gut-brain connection. Researchers are working to better understand the ways that our brains, organs and nervous systems communicate with each other, and how this might go wrong.

One thing’s for sure: Visceral pain isn’t “all in your head." But it is a little bit. That makes it trickier to target than a mechanical problem, but it also gives you some power. By activating the power of your brain, you can work to change your own neural pathways to reduce pain.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have issues with your digestive system, you need a team of experts you can trust. Our gastroenterology specialists at Cleveland Clinic can help.