Dextrocardia is a rare congenital heart defect in which your heart is on the right side of your chest rather than the left. This change to your anatomy doesn’t cause symptoms and it’s not dangerous. But it may occur along with other heart defects or genetic disorders — like situs inversus or heterotaxy syndrome — that need treatment.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/23125-dextrocardia-illustration)

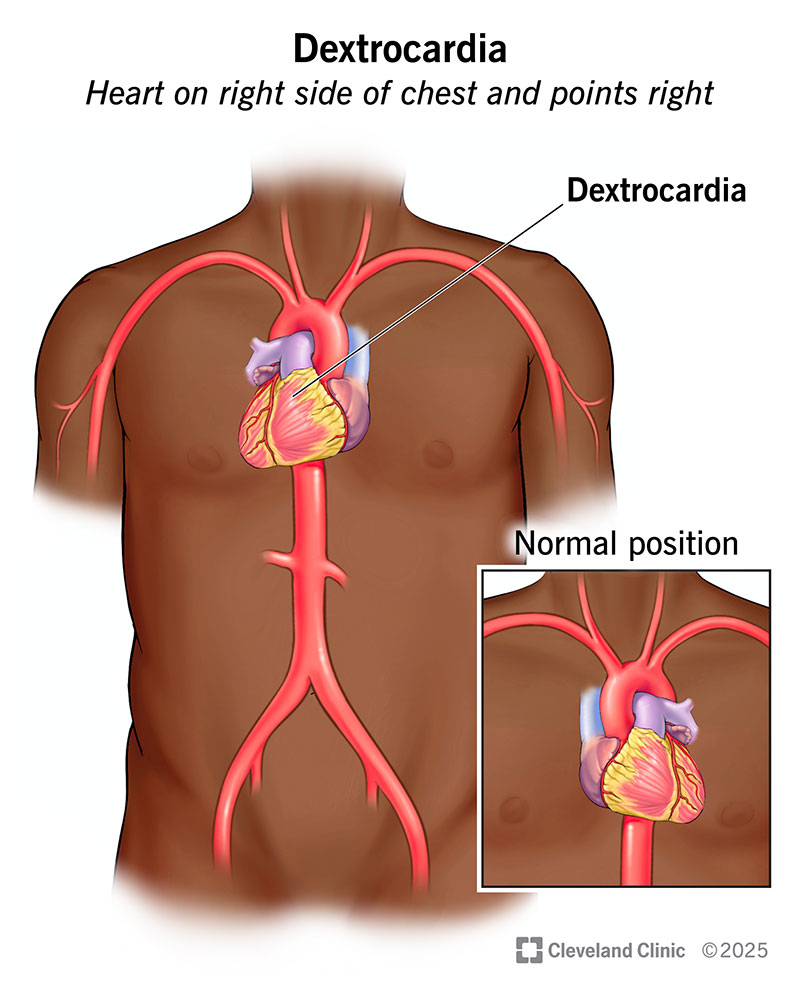

Dextrocardia is a change in how your heart is positioned in your chest. It means your heart is on the right side of your chest and points to the right. This makes it a mirror image of a typical heart. Normally, your heart is on the left side of your chest and points to the left. Dextrocardia is a congenital heart defect, meaning you’re born with it.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

On its own, dextrocardia isn’t serious. It doesn’t cause symptoms or complications. And it doesn’t need treatment. But many people with dextrocardia are also born with other conditions. And those conditions may cause problems that need medical attention.

Dextrocardia is rare. It occurs in about 1 in every 12,000 pregnancies.

Dextrocardia can occur on its own or along with other changes to your anatomy. You might have:

Advertisement

Isolated dextrocardia doesn’t have symptoms. You might not know your heart is on the right side of your chest until you have an imaging test for another reason.

But dextrocardia can occur along with other heart defects or genetic disorders. These conditions often cause the following signs and symptoms — often early in life:

If your child has any of these issues, their provider will do testing to find the cause. Even though dextrocardia doesn’t cause these symptoms, it may show up in the test results.

Gene changes that happen early in pregnancy cause dextrocardia. More than 60 genes play a role in how your organs are positioned in your body. Researchers are still looking for the specific gene that causes dextrocardia.

About 1 in 4 people with dextrocardia also have primary ciliary dyskinesia. Changes in more than 30 different genes, including DNAI1 and DNAH5, can cause this genetic disorder. Some people can be “carriers.” This means they have a gene change but no signs of the condition.

Healthcare providers sometimes diagnose dextrocardia in a developing fetus. They use prenatal ultrasound to check how the fetal heart and other organs are developing. This imaging test may show dextrocardia or other changes in fetal anatomy. Providers may also use a test called a fetal echocardiogram to get a more detailed view of the heart.

But if tests during pregnancy don’t reveal any issues, then a diagnosis might not happen until after birth. Some babies show signs of congenital heart disease soon after birth. This leads providers to run tests to find the problem. But dextrocardia itself doesn’t cause any symptoms. So, children without noticeable heart issues or genetic conditions might not get a dextrocardia diagnosis until years later.

To diagnose dextrocardia in babies, children and adults, providers use a physical exam and testing. During an exam, your provider uses a stethoscope to listen to your heart. A noticeable heartbeat on the right side of your chest can be a sign of dextrocardia.

If providers suspect dextrocardia, they may do more tests, including:

Isolated dextrocardia can show up on these tests — especially an EKG — as an incidental finding. This means that your provider was looking for something else, but the test happened to show dextrocardia.

Advertisement

People who receive a dextrocardia diagnosis are often diagnosed with other forms of congenital heart disease at the same time. These include:

Isolated dextrocardia doesn’t need treatment. But it’s important to share this diagnosis with any healthcare providers giving you care. This difference in your anatomy can be helpful for them to know during certain tests and procedures.

If you have dextrocardia along with other heart defects or a genetic disorder, your provider will tailor treatment for those other conditions to your needs. Treatments might include medicines, procedures or surgeries.

Treatment for heart defects — especially severe forms — often happens during childhood. This can be stressful if it’s your child who needs the care. Know that your child’s care team will offer support and guidance. They’ll explain exactly what your child needs. And they’ll help you know how to care for your child at home.

If your child has dextrocardia, talk with their healthcare provider about what to expect. You may need to look for symptoms related to heart defects or syndromes.

Advertisement

If you have dextrocardia, talk with your healthcare provider about how other conditions may affect your body. Your provider will tell you which symptoms to look for and how to manage them.

A person can live with dextrocardia for a long time, but the outlook varies based on other diagnoses. Babies born with isolated dextrocardia (no defects or syndromes) have a normal life expectancy. But babies born with heart defects or genetic syndromes may need treatments or surgeries to manage those conditions. Talk with your healthcare provider about what to expect and the long-term outlook.

Dextrocardia is rare, but we’ve learned a lot about it over the years. It was one of the earliest congenital heart changes identified by scientists — all the way back in the 1600s! Today, we know it can occur on its own or as a feature of some genetic disorders. It’s also common for babies with dextrocardia to have other forms of congenital heart disease.

If you or your child has dextrocardia, lean on your healthcare provider for guidance. They’ll explain if there are other issues that need treatment. And be sure to tell all your providers about your unique heart anatomy. They may need to know this detail when taking care of you.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your heart needs some help, the cardiology experts at Cleveland Clinic are here for you. We diagnose and treat the full spectrum of cardiovascular diseases.