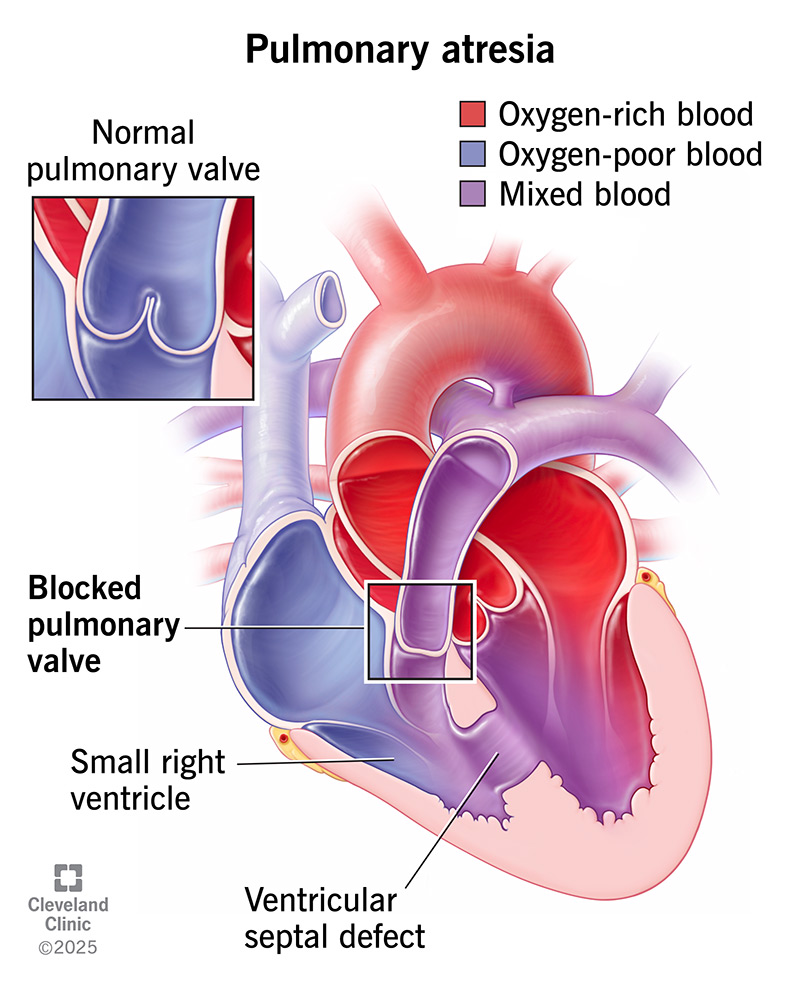

Pulmonary atresia is a congenital heart defect, which means it’s present at birth. With this issue, an infant is missing a functional pulmonary valve that normally helps blood get to your pulmonary artery. Blood travels from there to your lungs, where it takes in oxygen. Without this valve, your blood can’t get enough oxygen for your body.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/14779-pulmonary-atresia.ashx)

Pulmonary atresia is a congenital heart defect (present at birth) in which your pulmonary valve doesn’t develop or stays blocked after birth. Without a working pulmonary valve, blood can’t flow through your pulmonary artery to reach your lungs, where it gets oxygen. Instead, oxygen-poor blood goes throughout your body.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Pulmonary atresia occurs in about 1 in every 6,700 live births in the U.S.

In addition to not having a typical pulmonary valve, a baby with pulmonary atresia may have:

The right side of your heart sends blood to your lungs to get oxygen. The left side moves oxygen-rich blood to the rest of your body through your aorta (the main artery in your heart).

Pulmonary atresia that occurs with a defect in this dividing wall is called pulmonary atresia with a ventricular septal defect (VSD). This opening in the wall (septum) between the right and left ventricles allows oxygen-rich blood to mix with oxygen-poor blood.

If you have pulmonary atresia with an intact ventricular septum, the wall between the left and right sides of your heart is whole (intact).

Advertisement

Pulmonary atresia symptoms often appear within the first few hours or days of a baby’s life. Their lips, fingers and toes may look blue because of a lack of oxygen in their blood (cyanosis). This is why healthcare providers consider pulmonary valve atresia a cyanotic heart issue.

Other symptoms may include:

The exact cause of pulmonary atresia is unknown. Pulmonary valve atresia occurs during the first eight weeks of a fetus’s development in the uterus.

Genetic factors, like an abnormal gene or chromosomal defect, may increase the chances of heart defects in certain families. Some children with genetic disorders like DiGeorge’s syndrome may be at greater risk for pulmonary atresia.

Risk factors for pulmonary atresia include:

Complications of pulmonary atresia may include:

Regular follow-up care can reduce or prevent these complications.

While you’re pregnant, your healthcare provider will do standard screenings to check on the health of the fetus. If they see something of concern on an ultrasound (using harmless sound waves), they can do a fetal echocardiogram. This also uses sound waves to get a closer look at the fetal heart.

After you have your baby, their provider will check their heart and lungs to find out if there are any problems. If they hear a heart murmur through a stethoscope, they’ll order noninvasive tests. These tests for pulmonary atresia may include:

Advertisement

Pulmonary atresia treatment depends on how the condition affects your child and on their general health, age and medical history. Temporary treatments include medication and procedures. Most children will probably need surgery to improve blood flow to their lungs. Medical procedures and surgeries can make your child’s condition better, but they aren’t cures.

An IV drug (injected into a vein) called alprostadil prevents the ductus arteriosus from starting to close as it normally would. Keeping this open lets oxygen-poor blood flow from your baby’s aorta to their pulmonary arteries in order to pick up oxygen.

A healthcare provider can place a stent inside the ductus arteriosus to make sure it stays open. Another option is to perform a septostomy to enlarge the opening in the wall between your baby’s upper heart chambers. This improves blood flow to their lungs.

The type of surgery your baby needs for a pulmonary atresia repair will depend on several factors, including:

In pulmonary atresia and a ventricular septal defect (VSD), the right ventricle is usually well developed and can pump blood to your baby’s lungs. Surgery involves closing your baby’s ventricular septal defect and placing a donated artery and valve between your child’s right ventricle and pulmonary artery. This lets blood flow through their right ventricle into their pulmonary artery and to their lungs.

Advertisement

In pulmonary atresia without a ventricular septal defect, your baby’s right ventricle is usually poorly developed. They need a series of three operations during the first few years of their life. These open-heart surgeries redirect the flow of oxygen-poor blood directly to their pulmonary artery and lungs:

After heart surgery, your child will need to spend a week or two in the hospital, with some of that time in the intensive care unit (ICU). They’ll need a breathing machine (ventilator) and a heart monitor. In addition, they’ll get medications through an IV to provide pain relief and lessen the work their heart has to do.

Some infants may have feeding problems or might be too weak to eat after surgery. They may receive nourishment through a nasogastric tube or high-calorie formula instead of, or along with, regular formula or your milk.

Advertisement

For the rest of their life, your child will have regular follow-up appointments with their cardiologist. This starts two to four weeks after leaving the hospital. They may have appointments at least every six months. Some children may need more heart procedures or surgeries as they grow older.

It’s important to monitor for complications after surgical repair. Over time, people who’ve had a Fontan procedure may develop signs of heart failure, liver dysfunction and abnormal heart rhythms. Some people need a heart transplant.

Having pulmonary atresia puts you at a higher risk of endocarditis. Your child’s cardiologist can tell you if they should take antibiotics before dental appointments.

You may want to ask your child’s healthcare provider:

Without treatment, pulmonary atresia is fatal because it makes your oxygen level low. But when your healthcare provider makes a diagnosis before or shortly after your baby’s birth, they can treat them to improve their oxygen circulation. Your baby may need several surgeries at different ages to keep improving their situation.

Pulmonary atresia life expectancy varies depending on how severe your child’s condition is and other individual factors. Survival rates are better today than they were in previous decades.

Most people who have a Fontan procedure (the last in the surgical series for pulmonary atresia) are alive 20 years later. But many have long-term complications. Some say a person who had a Fontan procedure and is now 35 years old has as many years of life left as someone who is already 72.

Without having surgery to fix pulmonary atresia with a VSD, half survive to age 1 and very few to 10 years of age. Most people don’t live into their 30s without surgery.

With pulmonary atresia, a child’s pulmonary valve doesn’t form. Children with tetralogy of Fallot (ToF) have a narrow pulmonary valve. In both cases, blood has a hard time getting through the valve. Babies with ToF have three other heart issues in addition to the narrow pulmonary valve.

It’s difficult to hear that your newborn has a heart problem. Don’t be afraid to ask your child’s healthcare provider questions about your child’s specific situation. Once you bring your baby home from the hospital, be sure to keep taking them to their follow-up appointments with their cardiologist. These regular visits help your child’s provider catch any complications that may develop.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Your child was born with a missing heart valve. Cleveland Clinic Children’s providers are here to help. We know what it takes to treat their pulmonary atresia.