An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a congenital heart defect. It’s a hole in the atrial septum, the muscular wall between the two upper chambers (atria) of your heart. Small ASDs usually don’t need treatment. Larger ones may require percutaneous (nonsurgical) repair or surgery to lower the risk of serious complications.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/11622-atrial-septal-defect)

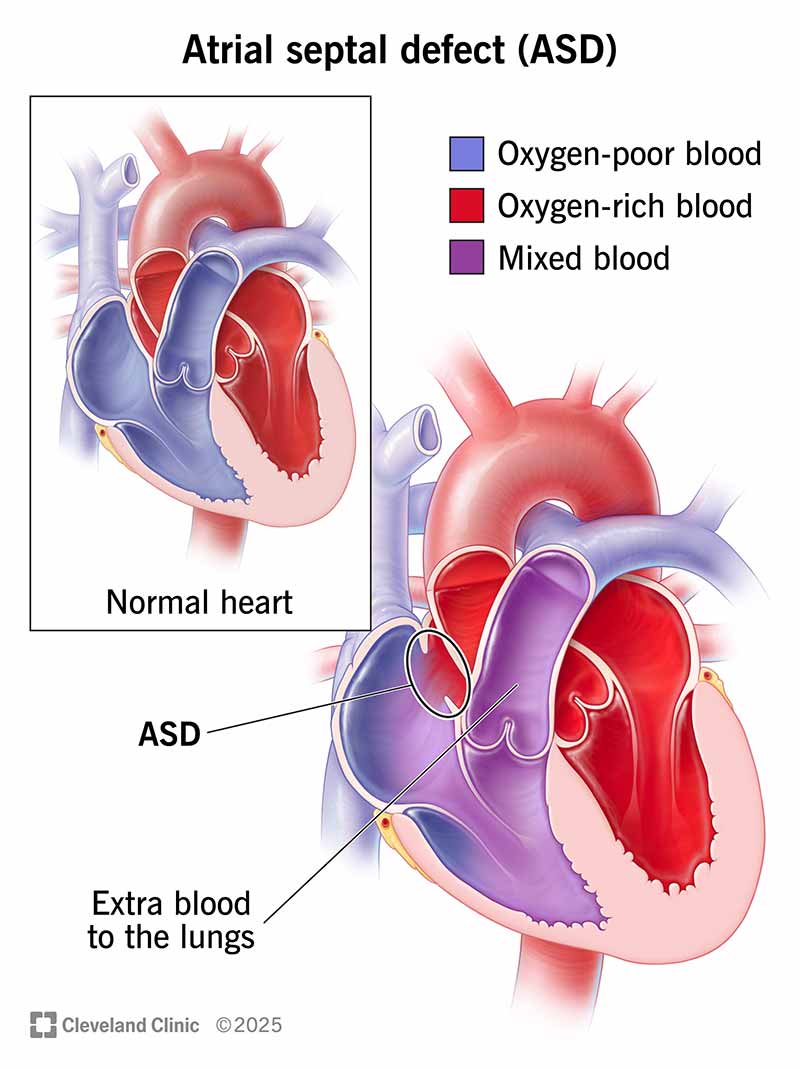

An atrial septal defect (ASD) is a hole in the atrial septum, which is the wall that separates your heart’s two upper chambers (atria). An atrial septal defect is a common congenital heart defect (something you’re born with). It happens when the septum doesn’t form properly. It’s also called a “hole in the heart.”

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

An atrial septal defect creates an abnormal route for blood. Some blood from your left atrium flows in the wrong direction, into your right atrium. Your right atrium contains oxygen-poor blood that needs to cycle through your lungs. So, your right atrium gets extra blood (with oxygen) that ultimately goes back to your lungs again.

Normally, oxygen-rich blood flows from your left upper chamber (atrium) down to your left lower chamber (ventricle), and then out to supply oxygen to your body.

A wrong-way leak might be minor and not cause any problems. In those cases, the atrial septal defect can be left alone without treatment. Other times, it can lead to problems with your heart or lungs. The bigger the ASD, the more likely it is to cause symptoms and need treatment.

An atrial septal defect isn’t the same thing as a patent foramen ovale.

There are four main types of atrial septal defects. Each has a different location in the atrial septum (wall).

Advertisement

Even though an atrial septal defect is present at birth, many people don’t have symptoms until far into adulthood. Small atrial septal defects (less than 5 millimeters) may not cause symptoms because they don’t strain your heart or lungs.

The most common (and often the only) sign of an atrial septal defect is a heart murmur. A healthcare provider will notice it when listening to your child’s heart with a stethoscope.

When children do have other atrial septal defect symptoms, they include a weight that’s less than what it should be, growth delays and recurrent respiratory infections. Rarely, children have fatigue when physically active, trouble breathing and abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmias).

Tell your child’s provider about any symptoms you notice. Their provider may want to run some tests to check your child’s heart structure and function.

Adults with an atrial septal defect may feel symptoms by age 40. Symptoms depend on how much the issue has strained your heart and lungs. They include:

If you have any of these symptoms, call your healthcare provider right away. These symptoms could mean you have an untreated atrial septal defect. Or they could mean you have another cardiovascular problem that needs treatment. If you have chest pain, you should call 911 or your local emergency number.

The exact cause of atrial septal defects isn’t fully known. But genetic changes that happen before birth often cause congenital heart defects. Some genetic variations associated with atrial septal defect affect the NKX2.5/CSX, GATA4 and TBX5 genes.

Some babies born with an atrial septal defect also have other heart defects or genetic disorders. These include:

If you’re pregnant, some factors can raise your risk of having a baby with congenital heart disease. These risk factors include:

A small atrial septal defect doesn’t affect your body much. But a larger one can strain the right side of your heart. That’s because it has to pump extra blood out to your lungs. This extra blood flow can slowly damage the blood vessels in your lungs as well.

Problems with large atrial septal defects include:

Advertisement

Healthcare providers diagnose atrial septal defects through a physical exam and tests that check your heart’s structure and function. Your provider will run one or more tests to learn how an atrial septal defect affects your heart. Possible tests include:

In some cases, a provider may use a cardiac CT scan or heart MRI. They’re most helpful for people with associated defects or less common forms of atrial septal defect.

Advertisement

Your healthcare provider may prescribe medications to treat some symptoms of atrial septal defect. But medications can’t close the hole. Providers can perform ASD closure through surgery or percutaneous (nonsurgical) repair.

It’s possible to live with an ASD in your heart if the hole is small. You usually don’t need a repair for a small atrial septal defect that doesn’t close by itself. Providers may recommend an ASD closure if an atrial septal defect is causing issues and hasn’t closed by age 2 or 3.

But you should get a repair for a larger ASD even if it isn’t causing symptoms. Treating it now prevents serious complications in the future, even for adults.

Once you have signs of heart or lung damage, atrial septal defect repair is essential. Your provider will recommend treatment if:

After a repair, you may need to take blood-thinning medication (anticoagulant or antiplatelet) for six to 12 months. These medicines keep blood clots from forming on the closure device (a rare complication).

You usually need to take antibiotics for at least six months following your repair. Antibiotics prevent an infection of your heart’s lining (endocarditis).

Advertisement

If you have an atrial septal defect, it’s important to keep all your medical appointments and follow your provider’s guidance. Atrial septal defects often call for “watchful waiting.” This means your provider keeps an eye on the situation to see when you need treatment. They’ll tell you how often you need to come in for appointments.

If you’ve had ASD repair, follow your provider’s guidance for follow-ups. You’ll likely go back for follow-ups after one, three, six and 12 months. Then, you’ll have visits once a year.

If your child has an atrial septal defect, their provider will let you know the next steps and when they might need treatment. In general, providers use “watchful waiting” for smaller atrial septal defects. Larger ASDs usually require procedures at a younger age to prevent future problems.

You may want to ask your provider:

After ASD repair, your child will likely have activity restrictions for a while as they recover. After that, they should be able to be physically active without limits.

The prognosis for a child with a repaired atrial septal defect is very good. Children usually don’t need any further treatment.

If you have an atrial septal defect, you may have a slightly shorter life expectancy. But life expectancy depends on many factors, including the size of the atrial septal defect and whether you have atrial septal defect repair.

The timing of repair also matters. Those who have atrial septal defect repair earlier in life have a better outlook. This is likely because early repair catches the problem before it can cause serious damage to your heart or lungs. The prognosis is worse in people who have complications.

Learning that you have a “hole in your heart” can be alarming. It’s even scarier if this happens to your child. But there’s good news. Modern medical advances have made atrial septal defects much more treatable than they used to be. And some ASDs don’t even need treatment because they’re too small to cause problems.

Talk with your provider or your child’s provider to learn more about the next steps. When possible, seek the advice and care of a congenital heart disease specialist at a high-volume hospital. These providers can manage your individual needs with the most advanced treatment options.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Congenital heart disease in children comes with a lot of questions and concerns. Cleveland Clinic Children’s has the answers and support you need.