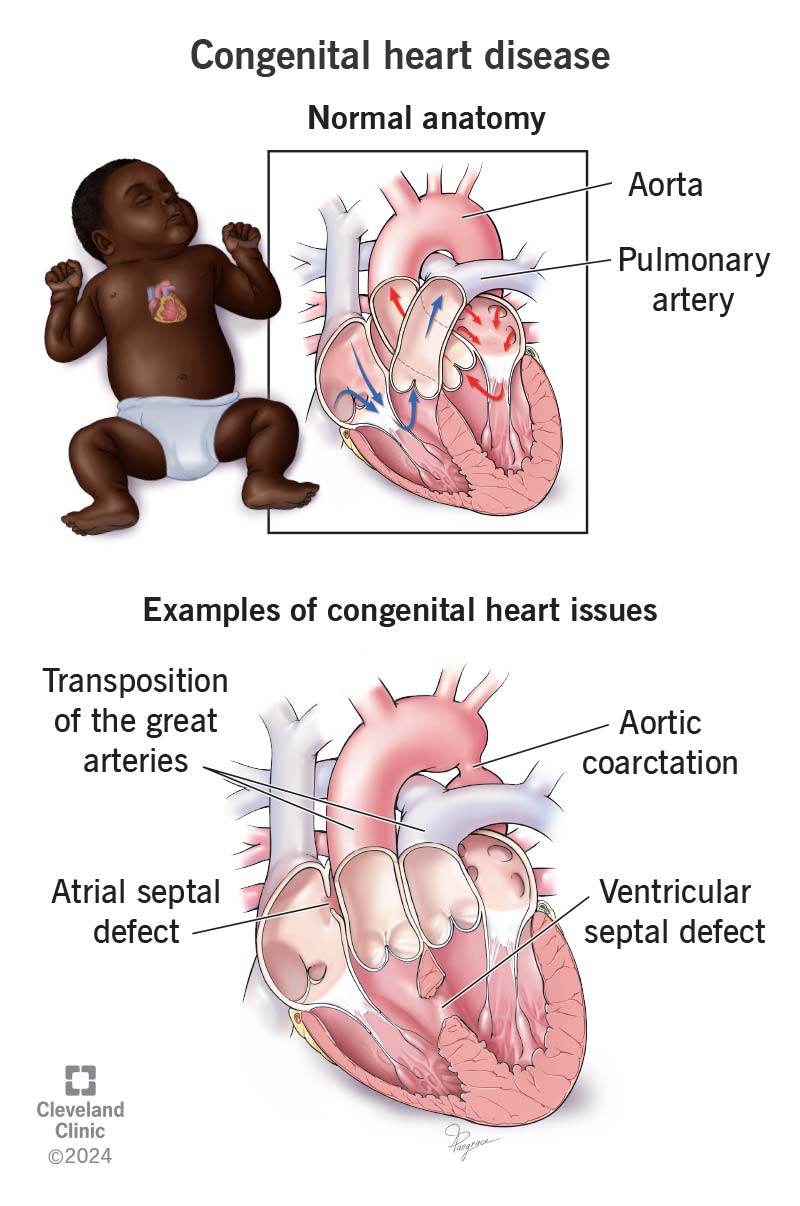

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is a problem with how your heart forms before birth. Some issues are more severe than others, but all of them prevent normal blood flow through your heart and beyond. Advances in diagnosis and treatment help most children with a CHD live to become adults.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/congenital-heart-disease.jpg)

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is an issue with your heart’s structure that’s present at birth. These issues — which keep blood from flowing normally — may include:

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Some cases of CHD are simple and may not cause any symptoms. But others can be life-threatening and require treatment in infancy.

Healthcare providers can detect heart defects early (before or shortly after birth). But sometimes, people don’t get a CHD diagnosis until childhood, adolescence or adulthood.

There are two main groups of CHD:

These heart anomalies reduce the amount of oxygen your heart can deliver to the rest of your body. Babies born with cyanotic congenital heart disease usually have low levels of oxygen and need surgery. Examples include:

Advertisement

This involves an issue that makes blood pump through your body in an abnormal way. For example:

Congenital heart disease is the most common type of congenital condition. CHDs affect 1% of U.S. births.

Congenital heart disease symptoms may start as soon as a baby is born or may not appear until later in life. They can include:

The signs and symptoms of congenital heart defects vary widely, depending on:

CHD happens when the fetal heart doesn’t develop correctly in the uterus. Scientists don’t fully understand why that happens, but it may be related to:

Researchers consider these to be the risk factors for congenital heart disease.

Congenital heart defects can make you more likely to have:

Sometimes a healthcare provider finds a congenital condition before a baby is born. If your provider finds anything unusual during a routine prenatal ultrasound, you and the fetus may need further testing. For example, a fetal echocardiogram uses harmless sound waves to create pictures of the fetal heart.

Advertisement

Providers detect other heart issues soon after a baby is born. For example, they can diagnose cyanotic CHD with pulse oximetry. The simple, painless test uses sensors on your baby’s fingers or toes to find out if oxygen levels are too low. Sometimes, people don’t get a congenital heart defect diagnosis until later in life.

Tests that can help diagnose CHD in newborns, children or adults include:

Congenital heart disease treatment may involve:

Advertisement

Some cases of CHD may not need any treatment. Others are life-threatening and need treatment soon after birth.

Complications of congenital heart disease treatment vary by procedure. They may include:

Depending on the procedure your child is having, they may need several days, a week or even several months to recover. Ask your child’s provider about recovery for the specific procedure they’re planning.

The outlook for people with congenital heart disease depends on the type of issue and its severity. Although serious cases can be life-threatening, many people with CHD live long, relatively normal and fulfilling lives.

Decades ago, only 10% of children with CHD survived into adulthood. Advances in diagnosis and treatment now help about 90% survive.

Even after you get a surgical repair, congenital heart disease is a medical condition you need to tell your providers about for years to come. Depending on your situation, you can develop problems from congenital heart disease later.

There aren’t any proven strategies to prevent CHD. People are born with it, usually from unknown causes. It’s beyond their control.

Advertisement

Scientists don’t have all the answers yet as to what causes congenital heart defects other than random gene mutations. But some things — like smoking, alcohol and certain medications — place you at a higher risk, and you should avoid these during pregnancy.

You should follow your healthcare provider’s instructions during pregnancy, including:

To keep your heart as healthy as possible and prevent complications of congenital heart disease:

You should see a cardiologist regularly throughout your life to monitor and manage congenital heart disease and detect any complications. You may need more than one treatment over time to address issues that develop.

Take a person with congenital heart disease to the emergency room or call 911 (or your local emergency service number) if they experience:

You may want to ask your child’s healthcare provider:

Just because a healthcare provider may use the term “congenital heart defect,” it doesn’t mean your child is defective. They can still live a fulfilling life with congenital heart disease. Treatments have come a long way and can help many children who have heart issues at birth. If your baby has a heart issue, it’s important to see a cardiologist who specializes in CHD. Learn all you can about your child’s issue so you know the best ways to help them.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Whether you were diagnosed as a child or later in life, Cleveland Clinic is here to treat your adult congenital heart disease.