Tricuspid atresia, a condition present at birth, is a heart problem in which your tricuspid valve doesn’t exist. Without this valve, blood can’t flow normally from your upper to lower chambers on the right side of your heart. Multiple surgeries at different ages help a baby’s heart work better. After surgeries, many people live into adulthood.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/tricuspid-atresia)

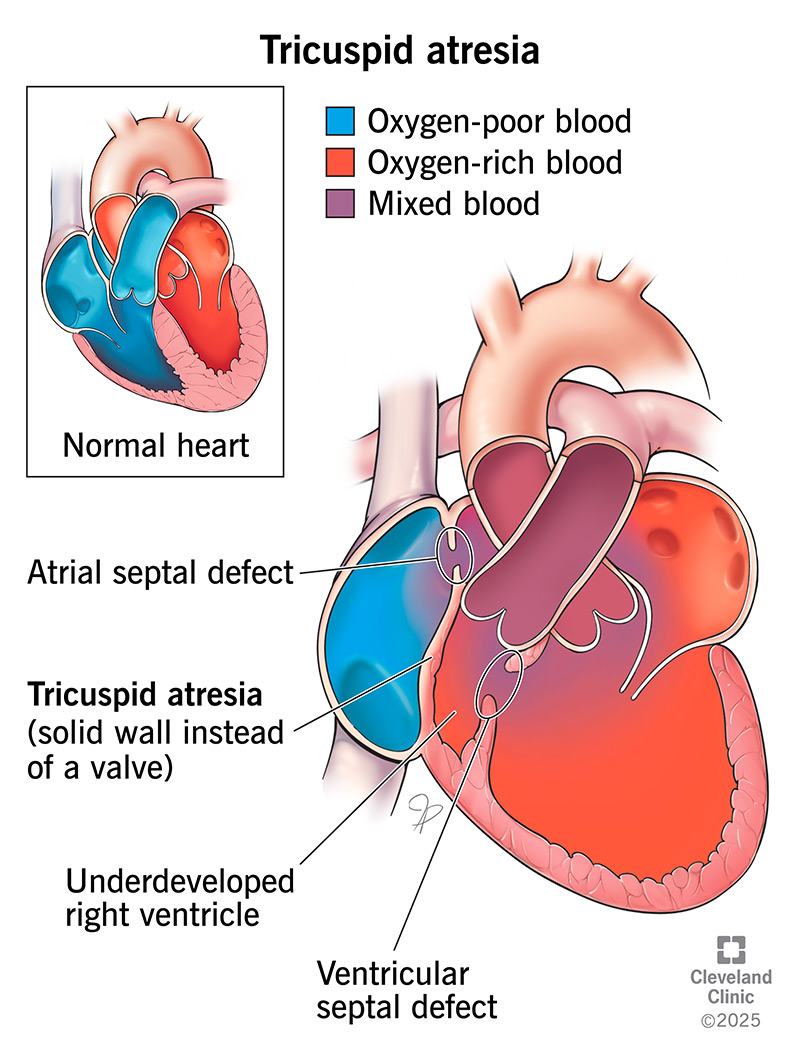

Tricuspid atresia is a congenital heart defect (present at birth) that occurs when the tricuspid valve doesn’t form. The tricuspid valve is normally between two chambers on the right side of your heart, the right atrium (upper chamber) and right ventricle (lower chamber).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

With tricuspid atresia, you have solid tissue instead of the tricuspid valve. This sheet of tissue blocks blood flow from the right atrium to the right ventricle, where blood would normally go. Because of this blockage, the right ventricle is usually small and underdeveloped. The other valve on the right side (pulmonary valve) between the right ventricle and your lungs can also be underdeveloped.

If you have this condition, you can’t get enough blood flowing through your heart and into your lungs, where it would get oxygen. Because of this, your lungs can’t provide enough oxygen to the rest of your body.

Tricuspid atresia is rare but is one of the more common complex congenital heart diseases. About 1 out of 10,000 babies born in the U.S. has tricuspid atresia.

Yes. Tricuspid atresia is one of the serious heart defects that healthcare providers consider critical congenital heart defects. This type of heart disease usually requires care in an intensive care unit with experience in complex congenital heart disease at birth. Frequently, a baby with tricuspid atresia has an urgent need for heart surgery before going home. Fatal complications occur without diagnosis and treatment.

Healthcare providers put cases of tricuspid valve atresia into different categories. Most people have Type I. Types I and II also have three subcategories based on other heart defects present.

Advertisement

Tricuspid atresia types are:

In most cases, babies with tricuspid atresia have symptoms within a week of birth.

Tricuspid atresia symptoms may include:

In addition, some babies with this condition can develop heart failure symptoms like sweating while feeding (in a newborn) or not gaining proper weight.

Although tricuspid valve atresia has known risk factors, the exact causes of it are unknown. Congenital heart diseases develop while a fetus is in the uterus and heart development is taking place. This can start in the first six weeks of your pregnancy.

Tricuspid atresia has a connection with VATER syndrome, trisomy and DiGeorge syndrome.

Babies are more likely to get tricuspid atresia or another congenital heart disease if they have Down syndrome or a parent who had a congenital heart defect.

Other risk factors (during pregnancy) include:

In a baby born with tricuspid atresia, blood flows from the upper right chamber (right atrium) to the upper left chamber (left atrium) of the heart through a hole in the septum, the wall between the chambers. This hole is always present during fetal life (foramen ovale). But sometimes, the hole is big and becomes a heart defect (atrial septal defect).

In some babies with tricuspid atresia, there’s an additional hole between their hearts’ two lower chambers (ventricular septal defect). Blood can flow through this hole and into the right ventricle, which will pump blood into their lungs.

When blood is flowing through these unnatural routes, blood high in oxygen blends with blood low in oxygen. In a typical heart, the two types of blood don’t mix.

Advertisement

Healthcare providers can diagnose tricuspid valve atresia before or after your baby’s birth. In developed countries, providers diagnose most babies before birth. They use an ultrasound (harmless sound waves) to create images. A fetal echocardiogram gives a better view if a more general ultrasound shows possible tricuspid atresia.

After your child is born, their provider can sometimes hear a heart murmur through a stethoscope. Providers usually diagnose tricuspid atresia with an echocardiogram (“echo”). This tracks the flow of blood and can show:

Other diagnostic tests (after birth) include:

Treatment for tricuspid atresia includes medicine and surgery, but they aren’t cures. Healthcare providers give your baby medicine first. They usually perform surgery shortly after a baby’s birth. Your baby will then have more procedures later.

Advertisement

Medication like alprostadil can help keep your baby’s patent ductus arteriosus open. This extra blood vessel, which normally closes after birth, lets blood flow from your baby’s aorta to their pulmonary artery. This provides an alternate way to send blood to your baby’s lungs to get oxygen. Without a tricuspid valve, the normal route doesn’t work.

Medicines may also help your baby’s heart muscle get stronger and their cells clear extra fluid out.

Surgeries for tricuspid atresia help your baby get more oxygen. The kind of surgery your baby has depends on their anatomy and other heart issues they have. Procedures include:

Advertisement

Recovery time after surgery for tricuspid valve atresia varies by procedure. Your child will likely be in the hospital for a week or two after a complex procedure. They’ll start out in an intensive care unit and then be in a regular hospital room for the rest of their stay.

Surgeries can help your baby’s heart work better and allow them to live past childhood. If the surgeries don’t help or their heart stops working properly, a heart transplant is an option.

If your child is having trouble breathing or eating, contact their provider.

With tricuspid atresia, your child will need regular visits with a heart expert (cardiologist) throughout their life. How often they have office visits depends on their age and treatment stage. Regular checkups help your child’s provider catch any complications that may be developing. After your child has a Fontan procedure, they’ll see their cardiologist at least once a year.

Your child’s cardiologist may also do tests, which can include:

Questions to ask your child’s provider may include:

Children with this condition can have complications between stages of repair. A healthcare provider may recommend home monitoring to improve outcomes for your child. They’ll instruct you on checking your baby’s weight and oxygen level, tracking their feedings and giving them medicine.

Your child will have to take preventive antibiotics before procedures like dental care. They may also need to limit physical activity that’s too demanding. Children with tricuspid atresia might have learning disorders or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Untreated tricuspid atresia is often fatal. Most babies with this condition won’t reach their first birthday without an operation.

But most children who have the surgeries survive and live to be adults. One study found that most people with tricuspid atresia are alive 20 years later. People who have the Fontan procedure have a life expectancy of 35 to 40 years, although they may need a heart transplant at an earlier age.

Although surgery isn’t a cure, the short-term and intermediate-term outlook for children who have surgery is promising. The outlook is usually worse for children who have surgery later in life.

Although healthcare providers don’t know the exact cause of tricuspid atresia, they do know that it happens before birth. If you’re pregnant or planning to become pregnant, you may reduce your baby’s risk of having tricuspid valve atresia and other complex heart diseases in these ways:

Both of these heart valve issues have to do with the tricuspid valve. With tricuspid atresia, there’s no tricuspid valve. With Ebstein’s anomaly, the tricuspid valve is there but doesn’t work right.

It’s upsetting to learn that your baby has an issue with their heart. But medical advances make the outlook for babies with tricuspid atresia better than in the past. Many children with this condition are growing up to be adults. Tricuspid atresia is a complex condition that normally requires surgery. Don’t be afraid to ask your baby’s healthcare provider any questions you have about this condition.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Learning your baby was born with tricuspid atresia can be stressful. Cleveland Clinic Children’s providers are here to treat this congenital heart defect.