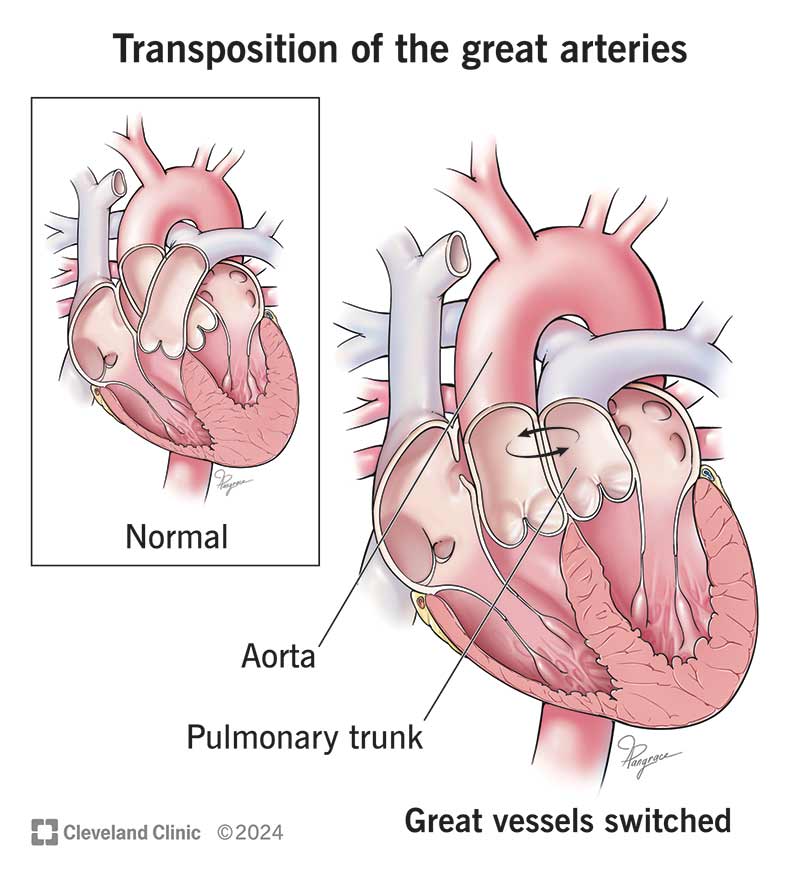

Transposition of the great arteries is a congenital heart condition that happens when the two main arteries going away from your heart are in the wrong places. For many babies with this condition, it affects blood oxygen levels and can be life-threatening without surgery to repair it. But the surgery has a very high survival rate.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/transposition-of-the-great-arteries-illustration)

Transposition of the great arteries (or vessels) is a rare issue where the main arteries that move blood out of your heart are in the wrong places. They also connect to your heart in the wrong places. It’s a congenital (present at birth) condition.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The two reversed (transposed) arteries are:

Your arteries are part of your circulatory system, which helps blood flow through your body. Unlike most arteries, which bring oxygen-rich blood to your body, your pulmonary arteries carry oxygen-poor blood.

With this type, a baby’s aorta is to the left of their pulmonary artery. In addition to the two major arteries, the lower section of your baby’s heart is also reversed. Blood without oxygen goes to your baby’s lungs and blood with oxygen goes to their body. But the wrong pumping chamber gets them there. This type is less common but also less harmful because blood goes where it should. Less than 1% of babies who have congenital heart conditions have the l-transposition type of TGA.

With this type, a baby’s aorta is to the right of their pulmonary artery. About 5% to 7% of babies with congenital heart conditions have this type of TGA. This type is the main focus of this article.

When your baby’s pulmonary artery and aorta connect to the wrong parts of their heart, it affects how blood travels. It can make it difficult for enough oxygen to reach your baby’s organs. This is because your baby’s blood skips going to their lungs for oxygen. Blood that has oxygen doesn’t travel throughout their body to deliver oxygen. This happens in babies with the d-transposition type.

Advertisement

Holes between your baby’s upper (atrial septal defect or ASD) or lower (ventricular septal defect or VSD) heart chambers may be present at birth, as well. Although they’re abnormal, these congenital conditions may help blood without oxygen to mix with blood that contains oxygen.

That amount of oxygen isn’t enough, though. Your baby will need procedures to ensure that enough oxygen reaches their whole body. While nobody likes to think about a baby having surgery, it’s the best solution for the long term. Surgeons have been doing these operations for decades — with high survival rates.

Newborns with d-TGA have symptoms of cyanosis (low oxygen) and may also have heart failure. Transposition of the great arteries symptoms include:

In a baby with the “d” type of TGA heart problem, signs appear soon after birth. Their severity depends on whether oxygen-rich blood can reach the rest of your baby’s body by “mixing” in the upper chambers of their heart.

Babies with d-TGA who have a large enough atrial septal defect may have less severe symptoms. That’s because ASD makes a hole for some oxygenated blood to get pumped into their body. Babies will also have a fetal blood vessel, called a patent ductus arteriosus, that allows mixing.

Some newborns don’t show symptoms right away because small openings around their hearts haven’t closed yet. Once the holes close, symptoms appear, and your baby requires immediate medical attention.

Researchers don’t know what causes transposition of the great vessels. Like other congenital heart conditions, it might result from a genetic variation (change) or exposure to toxins during pregnancy.

A baby may be more likely to be born with TGA if, during pregnancy, you:

Your healthcare provider may diagnose transposition of the great vessels during pregnancy. Prenatal tests check for congenital conditions.

If your provider notices a concern during a prenatal ultrasound, they may recommend a fetal echocardiogram. This noninvasive test is a detailed ultrasound. It can confirm a d-TGA diagnosis.

If providers don’t diagnose d-TGA during your pregnancy, they typically diagnose it within your baby’s first week of life.

To diagnose transposition of the great arteries, providers can use:

Advertisement

Babies born with the “d” type of transposition of the great arteries need surgery to survive. Many babies with d-TGA have surgery within the first week of life. Surgeons perform an arterial switch procedure, which involves switching the positions of your baby’s aorta and pulmonary artery. It restores a typical pathway for blood to flow through their heart and out to their body. If your child has a VSD, a surgeon will repair it at the same time using a synthetic patch.

Your child’s care team may use other treatments to delay major surgery for a short time until your baby can handle the procedure better. These include:

While surgery doesn’t cure d-transposition of the great arteries, most people with the condition can lead full, healthy lives. But people with this congenital condition need lifelong care. A cardiologist (heart specialist) monitors your progress to help you manage complications.

Advertisement

The survival rate after an arterial switch surgery is more than 95%. This survival rate stands even 25 years later.

Your child can live a full life after treatment for transposition of the great arteries. For either type of the condition, their heart needs lifelong follow-up care, including:

Many cardiologists don’t recommend competitive sports after d-transposition surgery. You and your child should talk to your pediatrician and cardiologist. Together, you can make a decision that’s best for your child’s health.

Many people who’ve had d-TGA surgery have had successful pregnancies. Talk to your healthcare provider and a cardiologist before getting pregnant. You may need to find a center that offers both high-risk obstetrical services and expertise in adult congenital heart disease.

There’s no known way to prevent transposition of the great arteries. But good prenatal care matters. Be sure your immunizations are up to date, take a multivitamin and keep prenatal appointments.

Advertisement

If you have a history of congenital heart conditions in your biological family, talk to your provider. They may recommend genetic testing and counseling before pregnancy.

After transposition surgery, people have a higher risk for other heart problems. Potential heart complications include:

Yes, your child may need more surgery later. The most common procedures are to restore their heart’s rhythm after a VSD repair or to repair heart valves.

Endocarditis is an infection that happens when bacteria enter your heart. It’s more common in people with heart conditions, like TGA. People who had transposition surgery may need to take antibiotics before dental procedures.

In addition to caring for your child’s heart issues, you may need to address possible differences in their brain development. Children who had an arterial switch operation may have ADHD or need special education services.

See a healthcare provider if your baby has:

If you had transposition surgery as a child, you need routine care and evaluation throughout your life. You should see a cardiologist with experience caring for adults with congenital heart disease.

If your child has transposition of the great arteries, you may want to ask your provider:

If you had surgery for this condition as a child, ask your provider:

Having a baby with a congenital heart condition isn’t in any new parent’s plans. But your baby’s healthcare providers can help guide you through the decisions ahead. It’s helpful to remember that providers have been treating babies with TGA for many years. Be an advocate for your child and their future. Don’t be afraid to ask questions about anything you’re unsure about.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your baby has transposition of the great arteries, breathing can be a struggle. Cleveland Clinic Children’s providers can treat their heart and help them thrive.