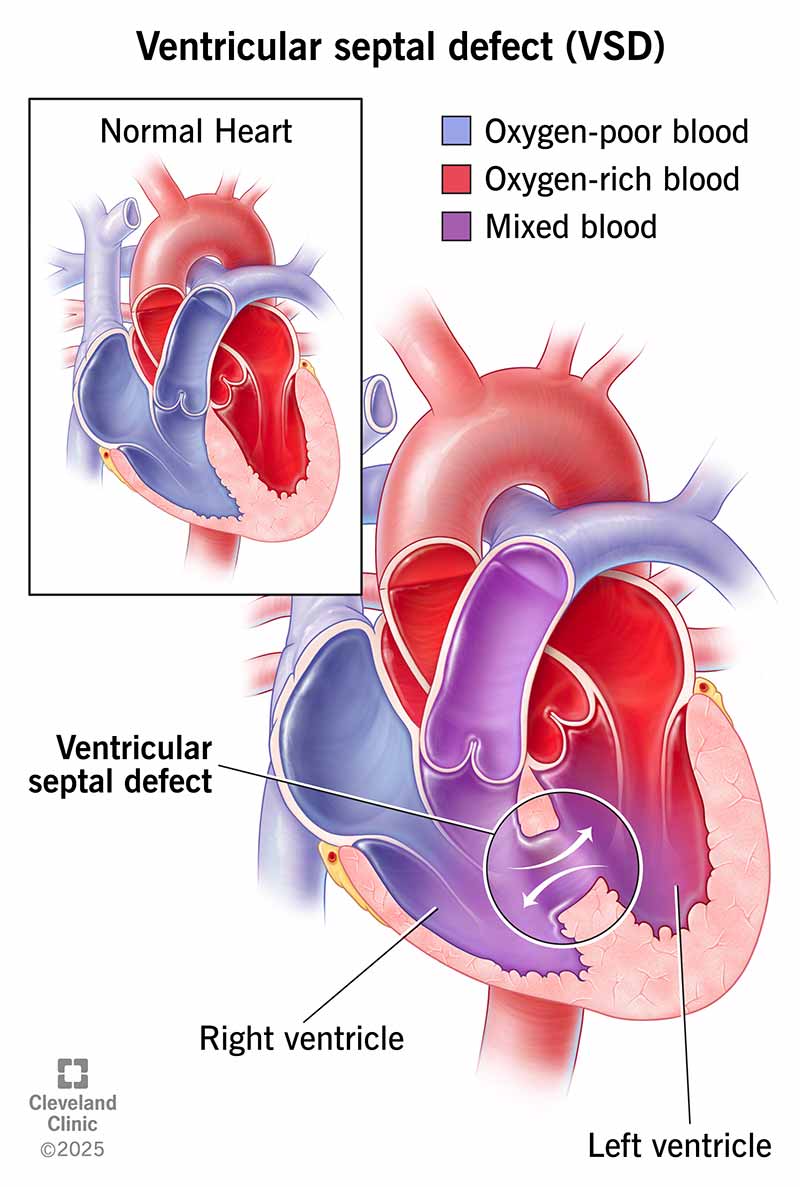

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the wall that separates the lower chambers of your heart. When this hole is large enough, the amount of blood leaking between the chambers can cause permanent damage to your heart and lungs and increase the risk of heart infections. Most VSDs don’t cause symptoms and close on their own by age 6.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17615-ventricular-septal-defect-illustration)

A ventricular septal defect (VSD) is a hole in the wall between the two lower chambers (ventricles) of your child’s heart. A VSD from an incomplete wall can allow oxygen-rich blood from one side of the heart to mix with oxygen-poor blood from the other. Your heart works best when the wall keeps blood from mixing.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

This condition is the most common kind of congenital heart disease (present at birth). It often happens along with other types of heart problems.

A small VSD is usually minor and has few or no symptoms. But a larger hole may need a repair to avoid permanent damage and complications.

Almost all VSDs are present when a child is a newborn. A VSD diagnosis happens most often during childhood. Rarely, you can get a diagnosis as an adult. This is much less likely because the defect closes on its own during childhood in most cases.

There are four main types of ventricular septal defects. They differ in their location and the structure of the hole (or holes). The types of VSDs are:

Advertisement

Ventricular septal defect symptoms in a newborn may look like heart failure. These include:

A VSD heart defect in older children and adults can make them feel tired or out of breath during physical activity.

Most people with VSDs don’t have symptoms because the hole is less than 3 millimeters around. This is about as big around as a toothpick and isn’t large enough to cause symptoms. But if the hole is large enough (or if there are multiple holes), it can cause blood to leak between the two heart chambers. A VSD that’s moderate (3 to 5 mm around) to large (6 to 10 mm around or about the size of a pea) may cause symptoms.

A ventricular septal defect doesn’t currently have any known causes. But it does sometimes happen along with other issues present at birth, like heart defects, heart conditions or genetic disorders like Down syndrome.

In very rare cases, a heart attack can tear a hole between the ventricles and create a VSD. This type of ventricular septal defect or rupture is technically a side effect. But it’s still a dangerous problem that needs to be repaired.

A VSD heart defect is slightly more likely to happen in premature babies and babies with certain genetic conditions. Taking anti-seizure medications (valproic acid and phenytoin) or drinking beverages containing alcohol during pregnancy may also increase the risk of a VSD. But it’ll take more research to confirm if these are definite causes.

A leak from a VSD makes your child’s heart pump less efficiently. Their heart needs to pump harder to make up for the reduced blood flow when the leak is larger. When their heart works harder long-term, it can cause symptoms and problems in their heart and lungs. These may become severe.

Pressure differences between the two sides of your child’s heart can lead to extra blood in their lungs. This can cause serious problems like pulmonary hypertension. Without surgery before age 2, a moderate or large VSD can lead to Eisenmenger syndrome. This damages the blood vessels in their lungs.

Other complications may include:

A healthcare provider can diagnose a VSD based on your child’s symptoms, a physical exam and imaging tests. Testing may not find a minor ventricular septal defect when the hole is too small to cause signs or symptoms.

Advertisement

A physical exam is one of the most common ways a provider discovers a VSD. That’s because a VSD that’s large enough causes a sound called a heart murmur. A provider can hear this when listening to your child’s heart with a stethoscope. They may even be able to estimate the size of the defect from the sound of a VSD murmur.

Tests can show changes in heart structure, heart rhythm and blood flow from a VSD. Tests that help diagnose VSD include:

The majority of VSDs are too small to cause any kind of problem. In those cases, a healthcare provider will watch for symptoms and see if the defect closes by itself. The ventricular septal defect will probably close on its own by age 6, but some take longer. A VSD is unlikely to close on its own after age 20.

For moderate or large VSDs, your child’s provider will likely recommend a VSD procedure or surgery to close the hole. In the meantime, medications can help.

Repair of a large ventricular septal defect before age 2 can prevent damage to your child’s heart and lungs. Without repair before this age, the damage becomes permanent and gets worse over time.

Advertisement

Medication can treat symptoms of a VSD before surgery or if the VSD is likely to close on its own over time. Common medications for ventricular septal defect are often the same as those that treat heart failure. They include:

The two main ways to repair a ventricular septal defect are:

In either case, your child’s heart tissue will grow over and around the patch or device, which will become part of their heart wall.

Recovery from repair of a VSD depends on the method a provider uses. Transcatheter procedures have shorter recovery times of days or weeks. Surgeries have longer recovery times, like weeks or months. Symptoms of a VSD usually decrease or disappear after surgery or transcatheter repairs.

If you or your child has a VSD, look for the usual symptoms of VSD or any sudden or unusual changes in symptoms. In general, you should go to the emergency room if you or your child has trouble breathing or any signs of cyanosis (pale or bluish skin, lips or fingernails).

Advertisement

Talk to your child’s healthcare provider if you notice any of these symptoms:

As an adult, talk to your provider if you:

You should also talk to a healthcare provider about your condition before you have any surgery or dental work.

Questions you may want to ask your child’s provider include:

In cases of a moderate or large VSD, repair of the hole is usually enough to prevent complications. In rare cases, your child may need follow-up surgery to close new leaks around the repair.

Most adults who live with a VSD don’t know about it because it isn’t large enough to cause any problems. But the larger the VSD (especially if unrepaired), the more likely it will affect how you live your life. An adult with a VSD will have it for the rest of their life unless they have a procedure to repair it.

Most people with a VSD have the same life expectancy as someone who doesn’t have a VSD. This is very likely if the ventricular septal defect is small and closes on its own.

But most people with a moderate or large VSD are more likely to have a shorter life expectancy — even after a repair. This is especially true if the VSD wasn’t repaired early. Those who develop Eisenmenger syndrome from a moderate or large VSD tend to have the worst survival outlook.

If your child has symptoms from a VSD, their healthcare provider will likely advise that they rest and avoid too much physical activity. This includes any activity that puts too much strain on their heart, especially if they have Eisenmenger syndrome.

Give your child medications exactly as instructed. Only change or stop giving them to your child if their healthcare provider tells you to.

If your child has a ventricular septal defect, it’s normal to feel concerned, anxious or even scared. If you’re dealing with these kinds of feelings, it’s a good idea to talk to the provider caring for your child. They can help you better understand the condition and what to expect. More importantly, they can help you find ways to treat this condition, prevent complications and minimize how it affects your child.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Some holes in your baby’s heart might close on their own. But if your baby needs treatment for a ventricular septal defect, Cleveland Clinic Children’s is here for you.