An atrioventricular canal defect is a congenital (present at birth) heart condition. It means there’s a hole in the center of your child’s heart and issues with their heart valves. It may affect some or all heart chambers. Babies with this condition usually need surgery soon after birth. After surgery, children need lifelong monitoring.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22173-atrioventricular-canal-defect-illustration)

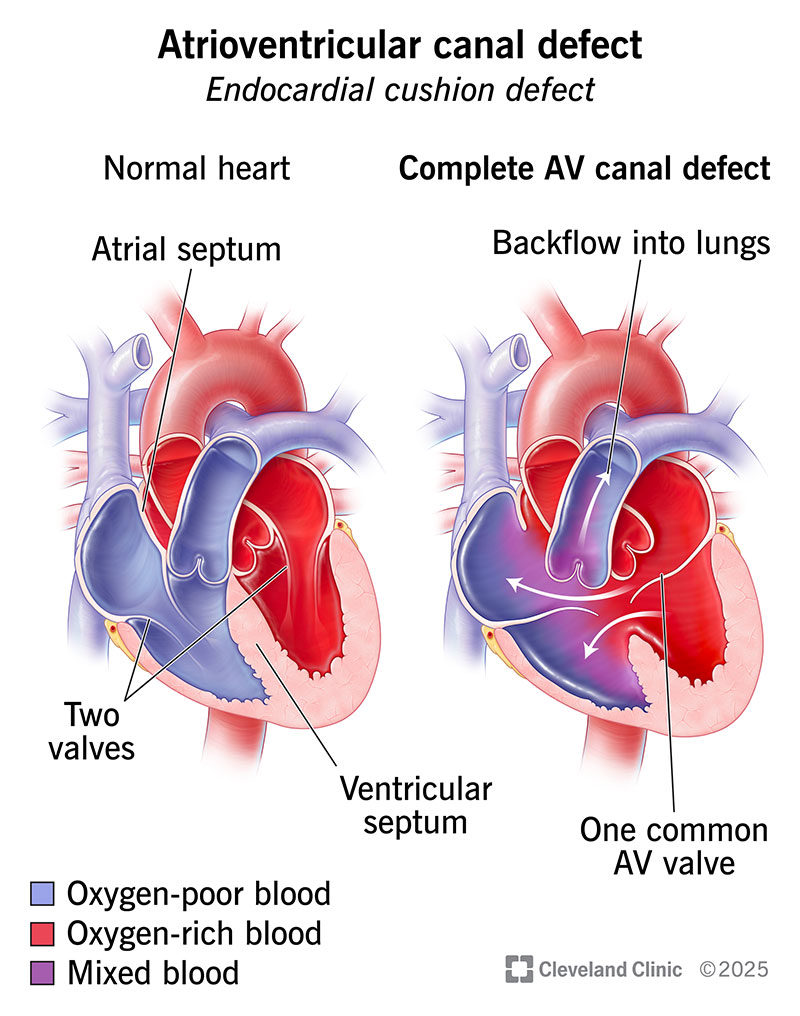

An atrioventricular (AV) canal defect is a congenital (present at birth) heart condition. It describes a group of several heart issues, including a hole in the wall (septum) at the center of your heart and problems with the way your heart’s valves work.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Having a hole in the wall that separates the right and left sides of your heart is like a pipe with a leak. It allows oxygen-rich blood (normally from the left side of your heart) to mix with oxygen-poor blood (normally from the right side of your heart). These don’t mix in a properly functioning heart.

In most cases, the hole allows too much blood to flow into your lungs and not enough blood to flow to the rest of your body. If the hole is present for a long time, blood with less oxygen may flow in the opposite direction. More of that blood goes to your body than your lungs. This can result in lower oxygen levels and cyanosis (bluish coloring of your skin). Darker skin may look gray or white.

By making your heart work too hard to pump blood, an AV canal defect can lead to a variety of health conditions like congestive heart failure.

Atrioventricular canal defect can be fatal in children who don’t get treatment. Without an operation, children with this condition may only live two or three years. But the good news is that the surgery to fix this has a high success rate. Providers can diagnose an atrioventricular canal defect in a baby before it can cause fatal complications.

About 1 in 1,700 babies are born with this defect each year in the U.S. It makes up between 3% and 5% of all congenital heart defects.

Advertisement

Other names for AV canal defect include:

An atrioventricular canal defect can take various forms, with differences in hole size and number of valves. The types of AV canal defect are:

Soon after birth, a baby may have atrioventricular canal defect symptoms like:

Babies with mild partial or transitional AV septal defect may not have symptoms until later in childhood, or even their teen years or early adult years.

Researchers are unclear about what causes atrioventricular septal defect. It’s likely a combination of genetic and environmental factors. There’s a strong link between this congenital heart condition and Down syndrome. Endocardial cushion defects occur in up to 40% of fetuses with this syndrome.

Experts haven’t identified the exact risk factors for atrioventricular septal defect. Genetics may be a factor. A fetus can inherit an abnormal gene or genes from a parent, which may make them more likely to develop a heart condition during fetal development.

Other risk factors during pregnancy that may increase the chances of giving birth to a baby with a congenital heart issue include:

Advertisement

A severe endocardial cushion defect can lead to:

A healthcare provider can often diagnose an atrioventricular septal defect before birth with a few tests:

A provider may use a stethoscope to listen to your baby’s heartbeat after birth. An abnormal “whooshing” sound may mean that blood is flowing through a hole in their septum. Other tests after birth might include:

Advertisement

In some cases, your baby may have a small septal defect that doesn’t cause symptoms right after birth. It might be several years before a healthcare provider detects the condition.

Treatment for AV canal defect ranges from surgery to medicines.

Atrioventricular canal defect treatment usually consists of open-heart surgery. During AV canal defect repair, a surgeon will put patches on the hole in your baby’s heart. In the case of a complete defect, they’ll also split the single heart valve into two separate valves on the right and left sides of your child’s heart.

A baby with an unbalanced AV canal defect may need several operations, leading to a Fontan procedure.

It’s best to do surgery as early as possible, before the condition causes lasting damage to your child’s heart. Many babies have the surgery during infancy, within their first six months of life. Some babies with a partial defect but no symptoms may get the surgery during their first three years of life.

Another option is a short-term procedure: pulmonary artery banding. This allows less blood to go through your child’s pulmonary artery to their lungs. Babies who receive pulmonary artery banding can have a permanent repair later.

Advertisement

A baby who isn’t healthy enough or large enough for surgery may need medication to manage symptoms until they gain weight and strength. Diuretics help clear excess water, while digoxin helps your baby’s heart beat more strongly. ACE inhibitors widen blood vessels to make it easier for blood to flow through them.

You should take your child to regular appointments with their pediatric cardiologist. They can monitor your child’s heart for any issues that develop. Some children with an endocardial cushion defect need more treatment after surgery. A patch can leak, and a repaired heart valve may develop a leak or get too narrow.

A child with an AV canal defect may also have neurological or developmental disorders. They may need help with these, as well.

Once your child reaches adulthood, they should switch to an adult congenital heart specialist for annual visits.

Questions you may want to ask your child’s doctor include:

Without surgery, children with an AV canal defect may have a life expectancy of two or three years. Some live to be young adults.

About 90% of children who have repair surgery have a 10-year survival rate. This means they live for at least another 10 years on average after treatment. About 65% are alive 20 years after surgery.

But even after surgery, someone with an atrioventricular canal defect won’t have a typical heart. They’ll need periodic echocardiograms to monitor their heart’s function and catch complications early.

The patch over the hole can usually stay in place for the rest of a person’s life. But over time, one of the repaired heart valves may begin to leak. About 10% to 20% of people need a second surgery.

After surgery, many people don’t need medications or more operations for their hearts. But cardiac arrhythmias may develop later in life. A provider may recommend minimally invasive procedures like ablation to treat an arrhythmia.

There’s no way to prevent an atrioventricular septal defect. But if you’re pregnant, you can reduce the risk of your baby having a congenital heart defect by:

Hearing that your newborn has a heart issue like atrioventricular (AV) canal defect can bring out a range of emotions. But your baby’s healthcare providers are there to help you, and they want the best for your child. Learn about the specific details of your child’s condition. Ask your child’s healthcare providers questions if there’s anything you want them to clarify. Now is the time to be an advocate for your child’s health.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Whether you were diagnosed as a child or later in life, Cleveland Clinic is here to treat your adult congenital heart disease.