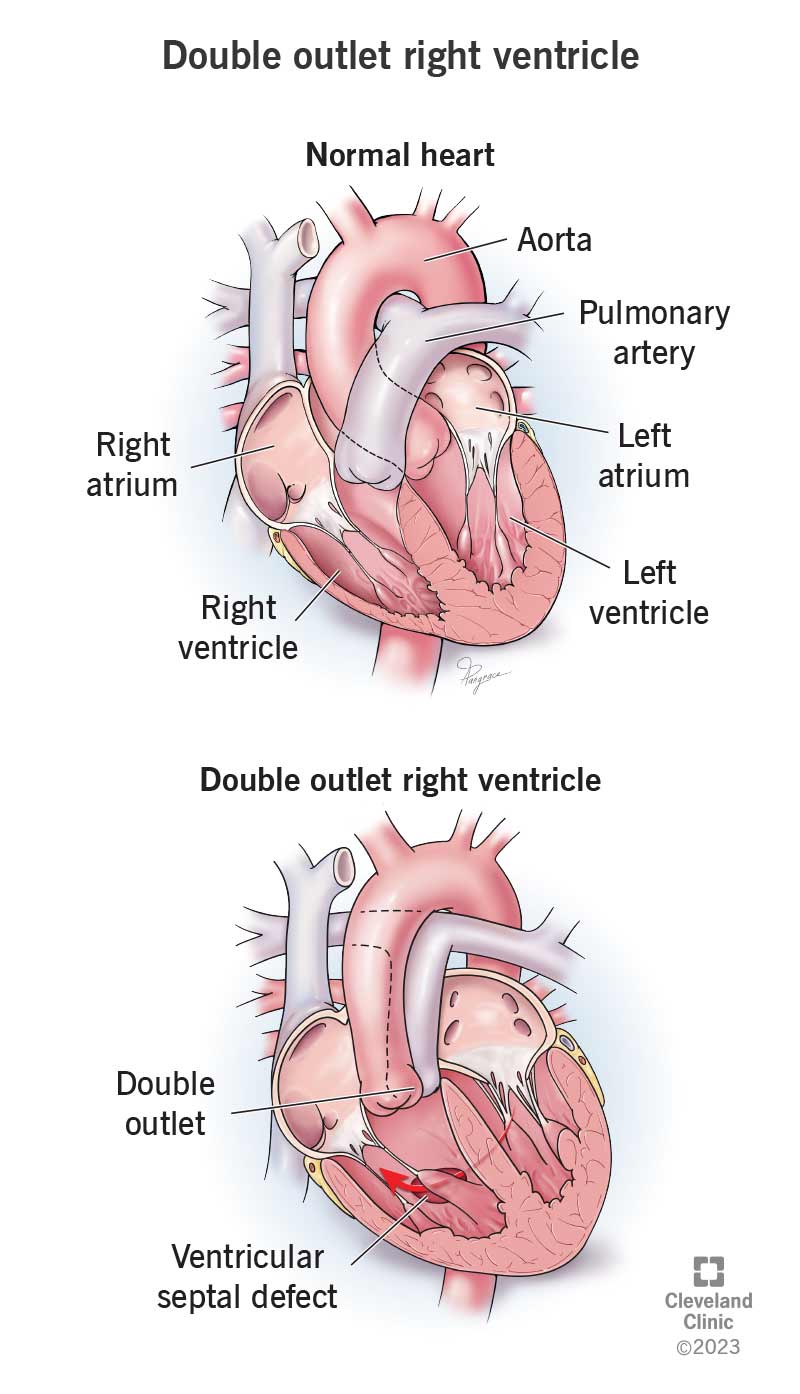

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) describes a heart with two major arteries linking to its right ventricle (heart chamber). Normally, only one of these arteries connects to each ventricle. The double link is a rare, congenital (since birth) heart issue. Surgery repairs the problem, but children born with DORV need lifelong follow-up care.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/double-outlet-right-ventricle)

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) is an abnormal heart condition in which two major arteries (instead of one) connect to your right ventricle or heart chamber. This is a congenital heart condition, which means you’re born with it.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Usually, each of your major blood vessels or “great” arteries connects to one of your heart’s two ventricles.

With DORV, both great arteries connect to the right ventricle — either totally or in part. Your left ventricle has just a part of one of the great arteries, or no artery at all.

Double outlet right ventricle can cause your body to receive oxygen-poor blood instead of blood with plenty of oxygen in it. Also, your lungs may receive excessive blood flow, which makes your heart work harder and can damage your heart and lungs.

Babies with DORV often have other congenital (since birth) problems:

Advertisement

Babies with DORV always have a ventricular septal defect (VSD), too. This hole in the septum or wall between the two ventricles lets blood flow through the hole and between the ventricles.

Healthcare providers classify DORV by the location of the hole:

DORV is rare. It happens just once for every 6,000 to 10,000 newborns.

Double outlet right ventricle symptoms usually appear during the first days or weeks after birth. They include:

Researchers don’t completely understand double outlet right ventricle causes. In 50% of cases, it happens to babies who have problems with their chromosomes, the cell structures that hold their DNA.

Possible complications of DORV include:

Sometimes, healthcare providers can find a heart defect before a baby is born. They may do this during a routine ultrasound screening called a fetal echocardiogram.

If not, a provider usually diagnoses double outlet right ventricle in the days or weeks after birth because of a baby’s symptoms.

During an exam, a provider will:

Your baby’s healthcare provider may order one or more tests, like:

Advertisement

Almost all babies with DORV need open-heart surgery within their first year of life. Your healthcare provider will help you make decisions about surgery by considering:

Your baby’s surgeon may take one of the following approaches to double outlet right ventricle repair:

Most babies have good outcomes from surgery for DORV. But any heart surgery has risks, such as:

Children who have a Fontan procedure may be in the hospital for a week or more. Recovery times vary by procedure and your child’s specific situation. Your surgeon will tell you what to expect.

Advertisement

Without surgery, a baby with double outlet right ventricle will eventually develop:

With surgery, most babies who have double outlet right ventricle live to be adults. Anyone who’s had surgery for DORV needs lifelong care from a cardiologist or provider who specializes in taking care of your heart.

People who had a surgical repair for DORV can carry a pregnancy. But providers don’t recommend it in certain situations. If you’re an adult who had an operation for this condition as a child, talk to your provider if you’re considering pregnancy.

With biventricular repair, people often live a normal life, with at least an average lifespan. People who need other procedures may have shorter lifespans and may need further surgery later in life. About 90% of people survive at least 10 years after surgery.

Because researchers are still trying to understand DORV’s cause, you can’t prevent it. You shouldn’t blame yourself, though. You didn’t make this happen.

It’s important to take your child to their follow-up appointments to make sure they’re not developing any issues. Your healthcare provider will tell you how often your child will need checkups or more tests. Also, make sure your child is taking any medicines their provider prescribed.

Advertisement

Because of the risk of infective endocarditis, some people with double outlet right ventricle need to take antibiotics before certain dental procedures. Whether you take an antibiotic or not, taking care of your skin and teeth can help prevent endocarditis.

Even after a surgical repair for double outlet right ventricle, a baby can have abnormal heart rhythms. Some people can develop heart failure years later. Contact your provider if your child has an abnormal heart rhythm or signs of heart failure, like chest pain or shortness of breath.

Take your child to the emergency room if they’re having trouble breathing and/or their nails, lips or skin have a blue tint.

Finding out that your newborn has a heart issue is very upsetting, to say the least. But it’s not your fault. Researchers don’t know the cause of it. Focus on finding out what you can about your child’s situation so you can make informed decisions. It can help to talk things over with a trusted friend or family member. Surgery and regular checkups can help people born with double outlet right ventricle live healthier, longer lives.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your child has a heart problem, it’s natural to be anxious. Cleveland Clinic Children’s can diagnose and treat double outlet right ventricle.