Metabolic syndrome involves having at least 3 out of 5 health conditions that increase your risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and Type 2 diabetes. It can cause other complications as well. Each condition is treatable with lifestyle changes and/or medication.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Metabolic syndrome is a group of conditions that together increase your risk of cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes and stroke. It can lead to other health problems as well, like conditions related to plaque buildup in artery walls (atherosclerosis) and organ damage.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Other names for metabolic syndrome include:

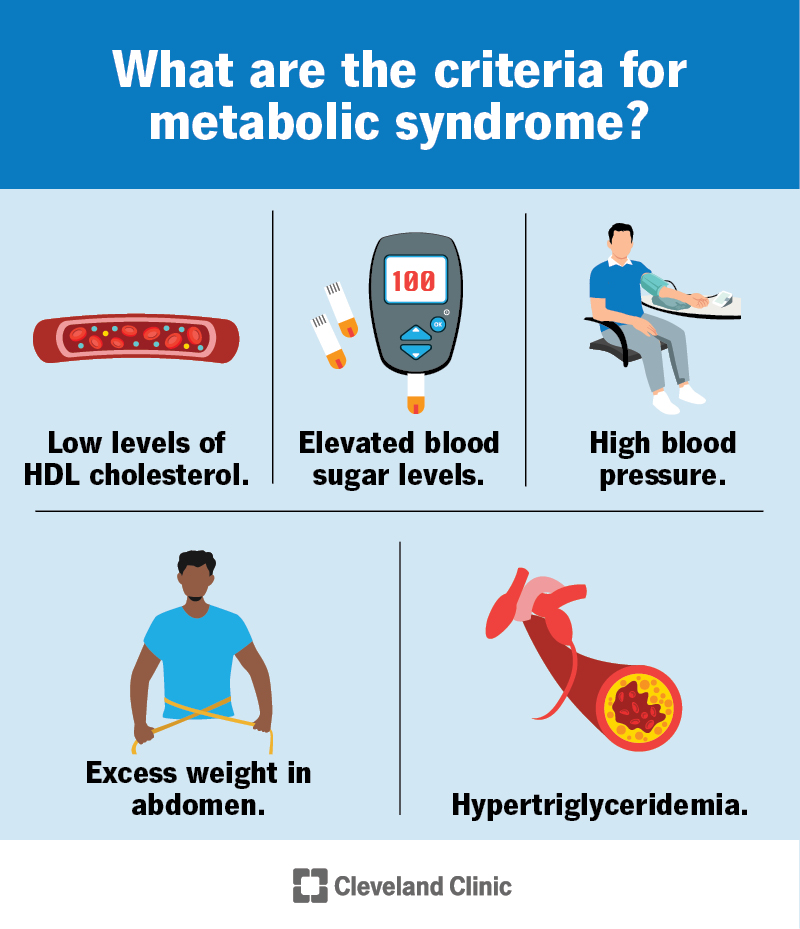

A person meets the criteria for metabolic syndrome if they have at least three of the following:

All of these conditions individually increase your risk of cardiovascular disease, Type 2 diabetes and stroke. But when you have three or more, your risk increases significantly. You should see a diagnosis of metabolic syndrome as a warning sign to try to change aspects of your health to lower your risk.

Metabolic syndrome is common in the United States. About 1 out of every 3 adults have it.

Advertisement

Not all aspects of metabolic syndrome cause symptoms. So, your symptoms will vary based on which of the five conditions you have. For example, high blood pressure, high triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol usually don’t cause symptoms.

High blood sugar (hyperglycemia) can cause symptoms for some people, like:

See a healthcare provider if you have these symptoms.

Several factors contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome — and it’s a complex web of factors. But researchers think insulin resistance is the main driver behind the syndrome.

Insulin resistance happens when cells in your muscles, fat and liver don’t respond as they should to insulin, a hormone your pancreas makes that’s essential for life and regulating blood glucose (sugar) levels.

For several reasons, your muscle, fat and liver cells can respond inappropriately to insulin. This means they can’t efficiently take up glucose from your blood or store it. This is insulin resistance. As a result, your pancreas makes more insulin to try to overcome your increasing blood glucose levels. This is called hyperinsulinemia.

If your body can’t produce enough insulin to effectively manage your blood sugar, it leads to high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) and prediabetes or Type 2 diabetes. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia can also contribute to:

The following can all contribute to insulin resistance:

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/10783-metabolic-syndrome)

A healthcare provider will do a physical exam and order blood tests if they think you might be at risk for or have metabolic syndrome. They’ll check your blood pressure and may measure the circumference around your waist.

They’ll order blood tests, like:

If you have at least three of the five criteria based on the results of these tests and the exam, you’ll have metabolic syndrome.

These blood tests are typically routine tests. So, your provider may tell you that you have metabolic syndrome (or are at risk for certain health conditions) after routine tests.

The main goals of treating metabolic syndrome are to lower your risk of heart disease and Type 2 diabetes if you don’t already have them. Treatment can involve medications and/or lifestyle changes.

Advertisement

Lifestyle changes are key to managing the conditions that contribute to metabolic syndrome. Changes include:

Advertisement

Various medications and treatments can help manage the conditions that contribute to metabolic syndrome. They include:

Yes, it’s possible to reverse metabolic syndrome. Lifestyle changes can do a lot to improve your health. Medications can help as well. Your healthcare provider will work with you to find the best plan for you.

Metabolic syndrome can lead to a wide range of complications, including:

The good news is that it’s possible to reverse metabolic syndrome with lifestyle changes and medications. The sooner you can make changes to protect your health, the better.

You can’t change all the factors that contribute to metabolic syndrome, like your genetics and age. But the lifestyle changes that can help treat metabolic syndrome are the same steps that can help prevent it.

If you have a family history of diabetes, high blood pressure or high cholesterol, be sure to tell your healthcare provider.

It’s also important to schedule routine provider visits. Your provider can keep track of your cholesterol, triglyceride, blood pressure and blood sugar levels. The sooner they can catch any issues, the sooner they can recommend lifestyle changes and treatments to reduce your risk.

If you have metabolic syndrome, it’s important to get ongoing care. You should see your healthcare provider for the following:

You may be overwhelmed to learn you have metabolic syndrome. Know that there are several strategies to manage or reverse it. Your healthcare provider will be with you every step of the way. Lean on them for support and advice. They’re available to help you.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Whether you’ve been living with diabetes for years or you’re newly diagnosed, you want experts you can trust. Our team at Cleveland Clinic is here to help.