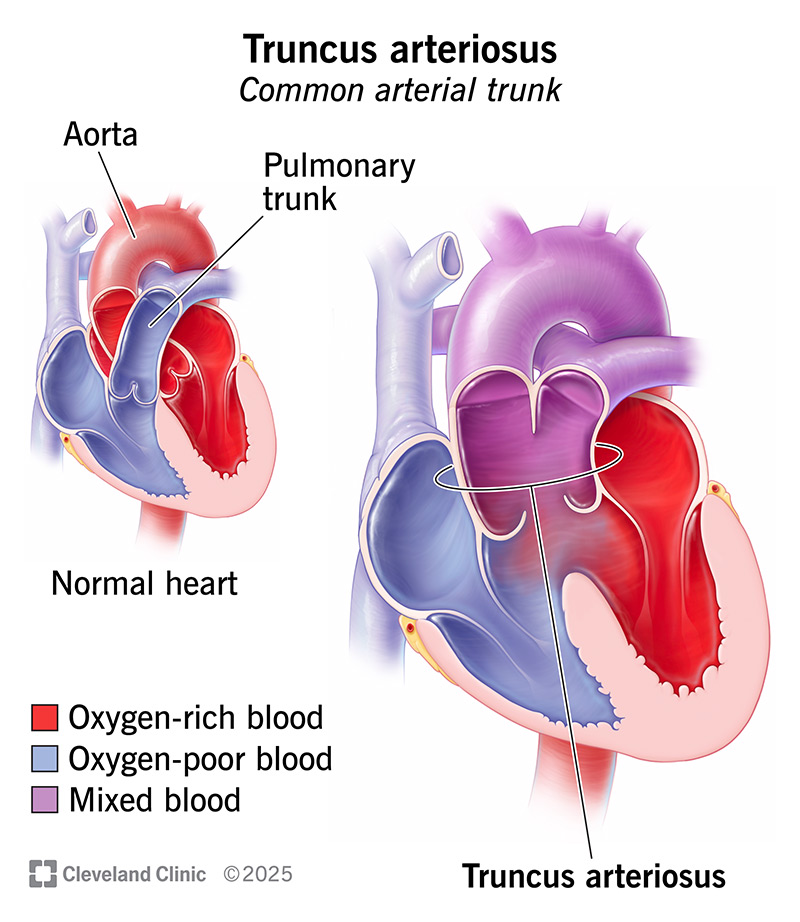

Truncus arteriosus is a rare congenital heart defect that affects how blood flows out of your baby’s heart. Instead of a separate pulmonary artery and aorta, your baby has a single vessel called a truncus. This interferes with normal blood flow to your baby’s lungs and the rest of their body. Surgery within weeks of birth can be lifesaving.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/14785-truncus-arteriosus)

Truncus arteriosus (also called a common arterial trunk) is a heart defect some babies are born with. It means your baby has just one, rather than two, arteries that carry blood out of their heart. And there’s just one valve, called the truncal valve, controlling this blood flow.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Normally, the main pulmonary artery sends oxygen-poor blood to your baby’s lungs. The aorta sends oxygen-rich blood to the rest of their body. But with truncus arteriosus, a single artery leaves your baby’s heart instead. As a result, oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood mix.

This inefficient system overworks your baby’s heart and lungs. It also prevents your baby’s organs and tissues from receiving enough oxygen. That’s why providers classify truncus arteriosus as a critical congenital heart defect. Your baby needs surgery soon after birth to correct the problem and have normal blood flow.

About 1 in 15,984 babies born in the U.S. have truncus arteriosus. It’s rare compared to other congenital heart defects. Of all babies diagnosed with a heart issue, around 2% have truncus arteriosus.

Signs and symptoms typically appear within the first few days of life and include:

About 1 in 3 babies with truncus arteriosus have DiGeorge syndrome. This means they may have symptoms affecting other parts of their body, too.

Advertisement

Scientists don’t fully understand what causes truncus arteriosus. In children born with certain genetic syndromes, like DiGeorge syndrome, the gene variations that cause the disorder are responsible for this heart defect. More generally, we know that truncus arteriosus happens when the fetal heart doesn’t develop correctly during pregnancy.

Normally, a fetal blood vessel called the truncus separates into two distinct arteries before your baby is born. The aortopulmonary septum (a wall of tissue) marks the boundary between the two vessels and prevents blood from mixing.

But for unknown reasons, the truncus might not form in this way. Instead, the truncus remains (persists) as a single common artery. That’s why providers sometimes call this condition “persistent truncus arteriosus.” The truncus itself is a normal part of fetal development, but it’s not supposed to persist past birth.

Your baby may have a higher risk of developing truncus arteriosus or other congenital heart defects if you’re pregnant and:

Babies with truncus arteriosus usually also have a ventricular septal defect (VSD). This is a hole in the wall that separates their two lower heart chambers (ventricles).

The hole causes blood from both ventricles to mix before passing through the truncal valve. This is the single valve that controls blood flow out of your baby’s heart. Normally, a baby should have two separate valves (aortic valve and pulmonary valve) controlling blood flow out of the two arteries.

Other heart defects that may occur with truncus arteriosus include:

Healthcare providers usually diagnose truncus arteriosus during a baby’s first few days of life when signs appear. If providers suspect a heart issue, they’ll perform an echocardiogram (echo). This test can reveal truncus arteriosus and other heart abnormalities.

It’s also possible for pulse oximetry — part of routine newborn screenings — to show low oxygen levels before symptoms develop.

Sometimes, providers notice truncus arteriosus before birth on a prenatal ultrasound. If your provider thinks there might be a heart defect, they may do a fetal echocardiogram. This test provides a more detailed look at fetal heart anatomy.

Your child’s provider may say your child has a specific type of truncus arteriosus. These types describe the anatomy of your child’s left and right pulmonary arteries, which carry blood to their lungs. These arteries normally branch off the main pulmonary artery. But with truncus arteriosus, the branch arteries start in different spots:

Advertisement

Other variations are possible. Providers use this knowledge of your child’s anatomy to guide surgery.

Babies with truncus arteriosus need heart surgery within the first weeks of life. The most common procedure is called a Rastelli repair, which creates two separate paths for blood to leave your baby’s heart.

Your baby’s surgeon will:

Advertisement

These are the basic steps for repairing truncus arteriosus. Your baby’s surgery may include other steps if they have other heart defects that need repair. Your baby’s surgeon will explain exactly what’s necessary for their unique heart anatomy.

Down the road, your child will need more surgeries to keep their heart and blood vessels working normally. For example, the artificial pulmonary conduit doesn’t grow with your child, so they’ll need a new one as they get older. Your child may also have issues with their heart valves.

Your child’s surgeon will tell you more about future surgeries and what they’ll involve. Your child will likely need another surgery within three to 10 years after their first one, and possibly more after that.

Follow the appointment schedule your child’s care team provides. Your child will need routine appointments with a heart specialist (pediatric cardiologist). They’ll transition care to an adult congenital cardiologist around their 18th birthday, and they’ll need to follow up with cardio for the rest of their life.

This ongoing care is very important. Your child’s providers will:

Advertisement

Yes, but they need surgical repair to survive. The survival rate for truncus arteriosus surgery is 80% to 97%, according to the latest research. Survival depends on many factors, including the complexity of a baby’s heart anatomy.

About 75% of babies who have surgical repair are alive 20 years later. Most deaths occur within one year of repair. About 92.5% of babies who survive to one year after surgery are alive at 20 years.

Your child’s care team can tell you more about the factors that might affect your child’s life expectancy.

There’s limited research on how truncus arteriosus (after surgical repair) affects a person’s quality of life. One study showed children have reduced exercise tolerance and a lower health-related quality of life compared to their peers. Another study showed adults have reduced physical functioning but a similar quality of life as their peers overall.

What it means to have a “normal life” can vary from person to person. Quality of life is a subjective experience. It’s important to talk to your child about how they’re feeling — physically and emotionally. As they get older, encourage them to ask their doctors questions. Even when you don’t have all the answers or know the “right” thing to say, simply being there for your child will help them feel loved and supported.

If you’ve just learned your baby has truncus arteriosus, you might feel scared or overwhelmed. You may want to learn every possible thing about this diagnosis and what it could mean for your baby’s future. Understanding the science is important. But it’s also important to know that congenital heart disease affects each person a little differently.

The statistics or outcomes you read about don’t necessarily predict your child’s future. They’re just a snapshot of what we know so far. Lean on your child’s care team for guidance. It may also help to connect with an organization that supports families of children with congenital heart disease.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

As your child grows, you need healthcare providers by your side to guide you through each step. Cleveland Clinic Children’s is there with care you can trust.