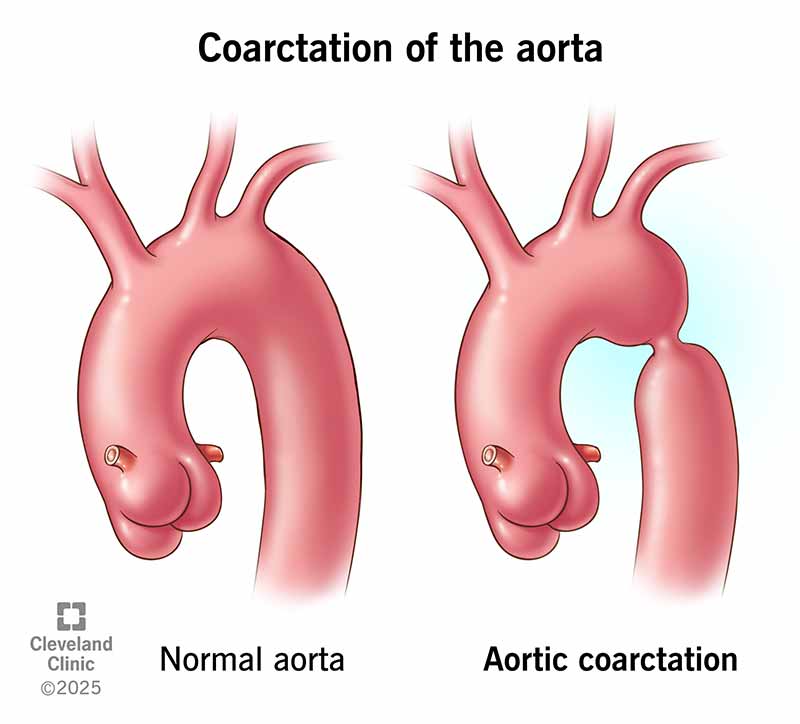

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a heart defect some babies are born with. CoA means your child’s aorta — a large artery — is pinched or narrowed in one spot. This interferes with normal blood flow in your child’s body and may overtax their heart. Your child needs surgery or catheterization to repair the problem and prevent complications.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/aortic-coarctation)

Coarctation of the aorta (CoA) is a congenital heart defect that affects your baby’s aorta. This is the artery that sends oxygen-rich blood from your baby’s heart to the rest of their body. “Coarctation” is a medical term for narrowing. With CoA, one part of your baby’s aorta is narrower than it should be. This makes it harder for blood to flow through.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

It might help to picture a busy highway and what happens when construction closes a lane. Traffic must slow down, and fewer cars can get through the narrowed stretch of road. Similarly, less blood can get through the narrowed part of your child’s aorta.

Typically, this “traffic jam” occurs before the arteries that branch off the aorta to carry blood to your child’s lower body. This causes higher blood pressure in your child’s upper body and lower blood pressure in their lower body. Such a blood pressure difference is the hallmark of coarctation of the aorta. It may lead to a diagnosis even if your child has no other symptoms.

Each year, around 1 in 1,700 babies born in the U.S. have aortic coarctation. Some babies also have other forms of congenital heart disease along with CoA.

Coarctation of the aorta symptoms depend on how narrow the aorta is. Typically, moderate or severe narrowing causes symptoms a week or two after birth. Mild narrowing may not cause symptoms until later in childhood, or at all.

Infants with CoA may have:

Severe coarctation in infants can cause shock and even death if not recognized and treated promptly. On the other hand, some infants have no symptoms because the narrowing is minimal.

Advertisement

Aortic coarctation symptoms in children and adults include:

Some kids don’t have symptoms they notice. Instead, high blood pressure at a routine well-check is the first sign of an issue.

In adults, symptoms usually mean the aortic narrowing has returned after a repair (this is called aortic recoarctation). It’s rare for CoA to go undiagnosed until adulthood.

Experts don’t fully understand what causes CoA. But they believe there’s a genetic component. Certain gene changes that happen before birth may keep your baby’s aorta from forming as expected.

These gene changes sometimes pass down within biological families. Research shows that if you have CoA, you’re much more likely to have a baby with CoA or another type of heart defect compared with those who don’t have CoA.

Certain genetic disorders can raise your risk of CoA. For example, babies born with Turner syndrome have a higher risk of aortic coarctation, bicuspid aortic valve and other congenital defects.

A common cause of CoA without any other heart defects (“isolated CoA”) is abnormal closure of the ductus arteriosus. The ductus arteriosus is a small artery that connects the fetal aorta and pulmonary artery. It helps a fetus get enough oxygen-rich blood when their lungs aren’t working yet.

Once a baby is born, their lungs start working. Since it’s no longer needed, the ductus arteriosus starts closing up within a few days. But when it closes, some tissue from the ductus arteriosus may blend in with tissue from the aorta. When this tissue tightens to close the ductus arteriosus, it may narrow the aorta, as well, and lead to coarctation.

Over time, coarctation of the aorta may cause a person to develop:

CoA is most dangerous when it’s undiagnosed and untreated. Ideally, diagnosis happens early in life so providers can offer early treatment and monitoring.

Pediatric cardiologists usually diagnose coarctation of the aorta during infancy or early childhood. The timing depends on the severity of symptoms.

Infants with moderate or severe symptoms are typically diagnosed soon after birth. Infants with mild or no symptoms may not be diagnosed until later in childhood when they begin to have high blood pressure. Aortic coarctation is rarely diagnosed in adulthood.

Advertisement

Most babies and children receive a CoA diagnosis when a physical exam reveals certain red flags. Signs that a baby or child may have coarctation of the aorta include:

Some newborns are diagnosed before they show visible symptoms. This happens when a pulse oximetry test shows low levels of oxygen in their blood. Low oxygen can be a sign of critical congenital heart disease. So, babies with low oxygen receive more tests to identify the specific problem.

Providers typically use an echocardiogram (echo) to diagnose CoA. They may also do other tests, like CT or MRI scans, to learn more about the anatomy of your child’s aorta.

Babies with CoA may also be diagnosed with other heart conditions. For example, about 45% to 75% of people with CoA also have a bicuspid aortic valve. This means the valve that sends blood from the heart into the aorta only has two flaps instead of the expected three.

CoA may also co-occur with:

Advertisement

Cardiac surgeons tailor treatment to your child’s unique heart anatomy. This means treatment might be more complex for a baby who has multiple heart defects compared to a baby who only has CoA.

Treatment depends on your child’s age, the severity of aortic narrowing and any other heart defects they have. Surgery is the gold standard for repairing CoA in babies and young children. Cardiac catheterization (less invasive than surgery) may be appropriate for older children who have mild coarctation. It’s also a treatment for children and adults who have recoarctation.

The most common repair surgeries for CoA include:

Advertisement

Babies with severe symptoms right after birth may need medication before having surgery. For example:

If your child has mild aortic narrowing or narrowing that returns after surgery, their provider may recommend:

Your child’s care team will tell you when to come in for appointments. Throughout life, your child will need follow-ups with a congenital heart disease specialist who can:

Thanks to improvements in diagnosis and repair, people with coarctation of the aorta can live to at least age 60. In the past, the average life expectancy for people with coarctation of the aorta was just 35 years old.

If your baby has coarctation of the aorta, you might be wondering why. We can’t always know the exact cause of congenital heart disease. But we do know that early diagnosis and treatment can lessen its impact on your child’s life.

Your child’s care team will be there to support your family. They’re prepared to answer your questions and help you understand what a CoA diagnosis means for your child. It may also help to connect with other parents of children with heart conditions.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your child is born with a heart condition, you’ll want the best care. Cleveland Clinic Children’s has experts specializing in aortic coarctation in children.