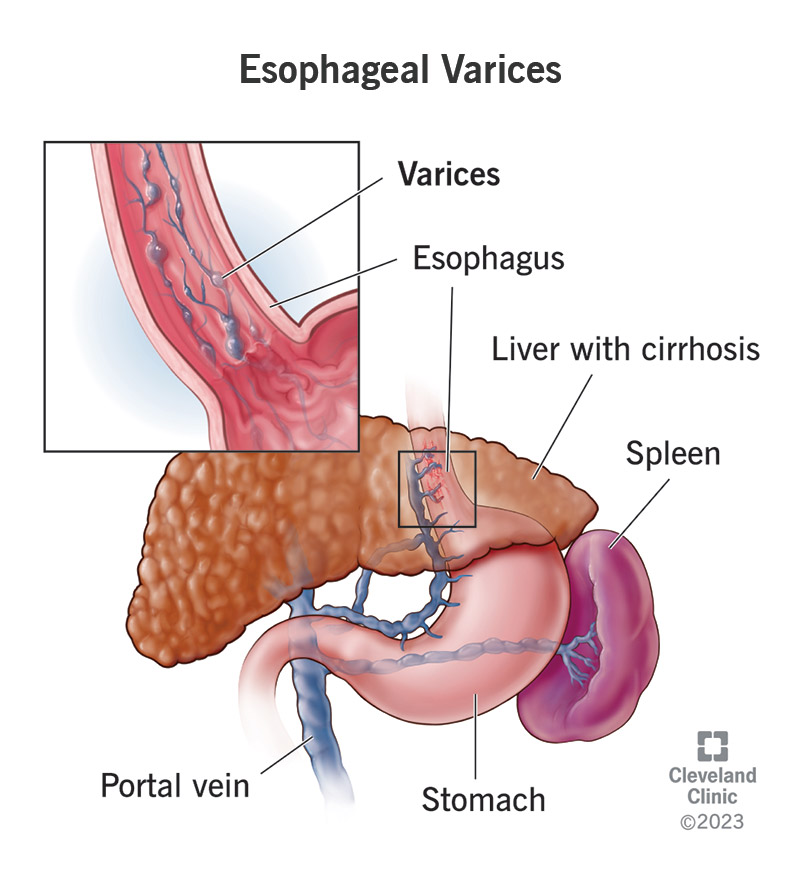

Esophageal varices are swollen veins in the lining of your esophagus. You can’t see or feel them, but it’s important to know if they’re there because they pose a risk of rupture and internal bleeding. They usually occur with liver disease. Most treatment is aimed at damage control.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/15429-esophageal-varices)

Esophageal varices are enlarged veins in the lining of your esophagus, the swallowing tube that connects your mouth to your stomach. Varices are serious because they have weakened walls that can leak or break and bleed. Internal bleeding from a ruptured vein can be sudden, severe and life-threatening.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Esophageal varices occur in people with portal hypertension, which is high blood pressure in the portal vein that runs through your liver and the other veins that branch off from it. Abnormal pressure causes the thin esophageal veins to swell and enlarge. This most often occurs in people with liver disease.

Bleeding is the most serious risk of esophageal varices. Not everyone will experience bleeding, but up to 50% will. The risk increases as portal hypertension increases. When portal hypertension results from chronic liver disease — which is most of the time — it worsens as your liver condition worsens.

People with advanced liver disease (cirrhosis) have other concerns besides esophageal varices. But bleeding varices are the most common cause of hospitalization and death in people with cirrhosis. An episode of variceal bleeding has a mortality rate of around 20%, and bleeding often recurs (comes back).

In people diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver, 30% already have portal hypertension and esophageal varices at the time of diagnosis. Up to 90% will develop them over the next 10 years. In general, more severe cirrhosis leads to increasing pressure and larger varices, which are more likely to rupture.

Advertisement

Esophageal varices aren’t visible from the outside like varicose veins in your leg might be. They’re deep inside your chest cavity, usually close to the bottom, where your esophagus meets your stomach. You’re not likely to feel them when you swallow. They usually don’t cause symptoms at all until they bleed.

A healthcare provider might suspect that you have esophageal varices if they see other signs suggesting portal hypertension or chronic liver disease. These might include:

If one of your varices ruptures, you probably won’t feel anything at the time. But look out for signs of gastrointestinal bleeding or blood loss. These might include:

Seek emergency medical care if you develop symptoms of severe blood loss and hypovolemic shock. These might include:

Esophageal varices are a direct consequence of portal hypertension, which is high blood pressure in your portal venous system. This includes the portal vein that runs through your liver and the smaller veins that branch off from it, sending blood back to your heart and into general circulation in your body.

Your body compensates for portal hypertension by redirecting blood flow into smaller veins that aren’t designed to handle the greater volume. The smallest of these, with the thinnest walls, become enlarged. These veins are in the mucous lining of your gastrointestinal tract: your esophagus, stomach and anus.

Because they’re so delicate and close to the surface of the organ, esophageal varices tend to enlarge more, rupture more often and bleed more heavily. Varices in your stomach or anus may also rupture and bleed. But this happens less often, and when it does, the bleeding is less often severe.

Gastric varices (in your stomach) usually produce small, slow bleeds that stop spontaneously. They cause bruising and tissue damage to your stomach lining (portal hypertensive gastropathy). Varices in your anus might resemble hemorrhoids, but you probably wouldn’t notice them unless they rupture.

Advertisement

Pressure gradually increases until a rupture occurs. There doesn’t seem to be any precipitating event, but rupture usually occurs when blood pressure in the vein has risen by 50% to 100%. Varices that bleed are usually larger than 5 millimeters. Smaller varices reach this size at an average rate of 8% each year.

The most common cause is cirrhosis of the liver. “Cirrhosis” means scarring. This is the result of long-term, chronic liver damage. Constant inflammation (hepatitis) in your liver tissues eventually turns them into scar tissue, which blocks the flow of blood through the portal vein. This is a gradual process that usually takes decades.

Cirrhosis is the end-stage of any chronic liver disease, including:

Other causes of portal hypertension include:

Advertisement

You probably won’t know until a healthcare provider checks you. If you’ve already been diagnosed with cirrhosis, your healthcare provider will probably recommend regular screening for varices. But people don’t always know that they have liver disease, even when it’s advanced.

A healthcare provider will evaluate your symptoms and health history, including any current or chronic conditions. An initial physical exam may show signs of bleeding, blood loss or liver disease. They’ll follow up with blood tests and imaging tests to look for evidence of portal hypertension and varices.

If you don’t have signs of active bleeding, your provider might begin with noninvasive imaging tests, such as a CT scan, magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) or Doppler ultrasound, to look at your blood vessels and blood flow. If they find evidence of varices, they might want to follow up with an endoscopy.

An upper endoscopy (also called an EGD test) is an examination of your upper gastrointestinal tract. That includes your esophagus, stomach and the top of your small intestine (duodenum). A gastroenterologist, a specialist in gastrointestinal diseases and endoscopic procedures, performs it.

The endoscope is a long, thin tube with a tiny camera on the end. It passes down your esophagus, into your stomach and duodenum. The camera projects to a monitor, showing your endoscopist what’s inside. If they find issues, they can treat them with instruments passed through the endoscope.

Advertisement

Healthcare providers have several ways of treating varices to prevent and control bleeding. Most treatment is aimed at damage control. Varices usually don’t reduce and go away, unless portal hypertension does. This may be possible in some cases, depending on the condition causing it.

The goals of treatment are to:

Bleeding from esophageal varices is an emergency that requires immediate treatment. Supportive care in the hospital may include:

When your condition is stable, you’ll have an emergency upper endoscopy to diagnose and treat the bleeding. Treatment during endoscopy will include:

Follow-up treatment after variceal band ligation includes:

If you’ve already been treated for bleeding, or if your varices aren’t bleeding yet but are at risk, your healthcare provider will offer you preventive treatment. Prevention generally includes:

If the above treatments don’t reduce your risk of variceal bleeding, or if you’re having other complications from portal hypertension, your provider might recommend alternative procedures to reduce portal hypertension in the portal vein itself.

Procedures include:

Portal hypertension may improve by treating the cause in some cases. If the cause is a blood clot or an infection that can be cured, curing these might cure portal hypertension. Liver damage can improve up to a point, depending on how far advanced it is. This also depends on what’s injuring your liver.

Possible ways to reduce liver damage include:

Varices sometimes reduce with treatment, especially if portal hypertension can be reduced. But they rarely go away completely. Once you’ve been diagnosed with esophageal varices, your healthcare provider will want to keep a close eye on your condition. Even with treatment, new bleeding is always a risk.

Your outlook depends on:

Only about 50% of people with esophageal varices have bleeding. But most people who have esophageal varices have other factors affecting their life expectancy. When liver disease advances to liver failure, it’s eventually fatal without a liver transplant. Other conditions also apply.

The state of your liver disease partly determines your risk of bleeding. And if you do have bleeding, the state of your liver disease greatly influences how well you’ll recover. Mortality from a single episode of bleeding ranges from 10% in early liver disease to more than 70% in the advanced stages.

In overall statistics:

Esophageal varices are among the most serious complications of portal hypertension and cirrhosis. But liver disease takes time to advance to this stage. If you catch it earlier, you can use the advantage of time to make lifestyle changes that may improve the course of your disease, preventing varices.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic providers compassionately diagnose and treat all liver diseases using advanced therapies backed by the latest research.