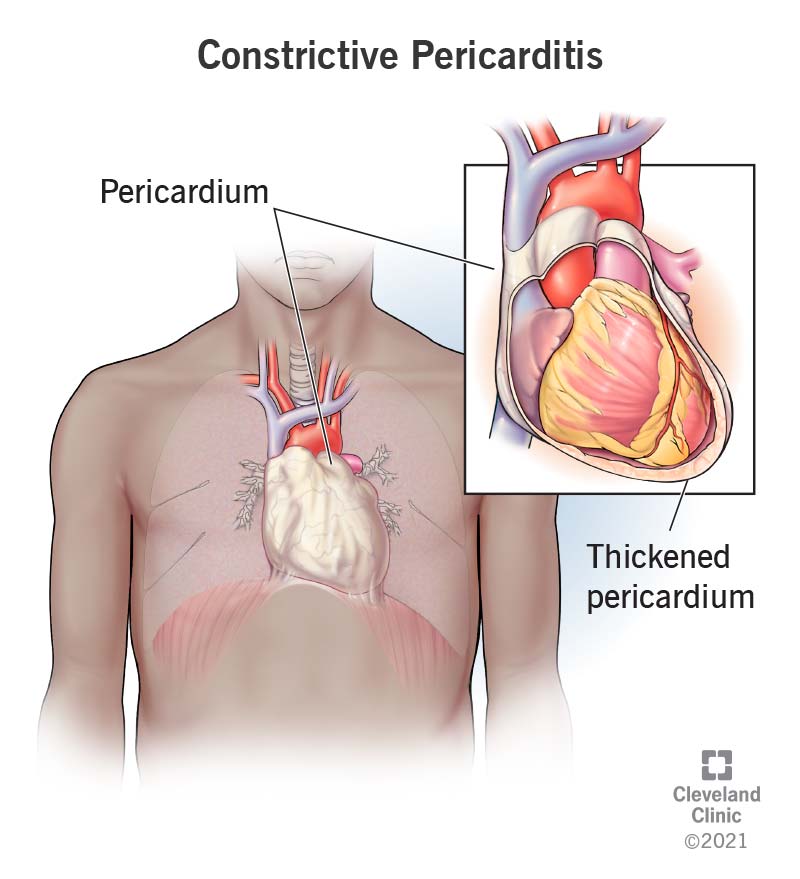

Constrictive pericarditis is a condition where the walls of the fluid-filled pouch around your heart, the pericardium, become too stiff or thick. That keeps your heart from beating properly and can cause severe complications over time. Depending on the severity, what caused it and your overall health history, it’s often treatable or even curable.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22373-constructive-pericarditis)

Constrictive pericarditis is a condition where the pericardium, the thin membrane that holds your heart in place, becomes stiffer and thicker than normal. That interferes with your heart’s pumping ability and can lead to severe problems like heart failure. It's usually a chronic (long-term) problem, but it is treatable in most cases, especially with early diagnosis.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The pericardium is a fluid-filled membrane with two layers that surrounds your heart. Part of the pericardium’s job is to hold your heart in place. There’s also a layer of fluid inside the pericardium between it and your heart. That fluid helps cushion your heart and protect it from injury.

Under normal circumstances, the pericardium is flexible and stretchy. That means your heart doesn’t have any trouble expanding to fill up with blood between heartbeats. The pericardium is stiffer and thicker than normal when you have constrictive pericarditis. That keeps your heart from expanding as it should.

When your heart can’t expand enough to fill up with blood, it struggles to pump enough to meet your body’s needs. To compensate, the filling pressures increase, which leads to heart failure.

These are the same condition, but "restrictive pericarditis" is no longer in common use.

Constrictive pericarditis is most likely to happen to people who have a history of heart surgery, radiation therapy around their heart, or idiopathic/viral pericarditis (idiopathic means “unknown”). In developing countries, tuberculosis is the most common cause. It’s two to three times more likely to happen to men than women. It’s also extremely rare in children.

Advertisement

Constrictive pericarditis is a rare condition overall. It happens to about 9% of people with acute pericarditis, and acute pericarditis accounts for about 5% of all chest pain-related emergency room visits.

The symptoms of constrictive pericarditis include:

Constrictive pericarditis has a few different subtypes:

Constrictive pericarditis means that your pericardium is stiffer or thicker than normal, often because of scar tissue from previous medical conditions. This stiffening of the pericardium can happen for several reasons, including.

Advertisement

No. While constrictive pericarditis can happen because of infections (some of which are potentially contagious), this condition isn’t contagious on its own.

A doctor can diagnose this condition based on a combination of your symptoms, your medical history, a physical examination and diagnostic tests. This condition is sometimes difficult to diagnose, especially when the symptoms aren’t severe or when you have other conditions with similar or related symptoms.

If a healthcare provider suspects you have constrictive pericarditis, the following tests are possible.

This condition is usually treatable, and curing it is often possible.

In most cases, curing this condition involves two main principles:

Most of the time, this condition involves the following:

Advertisement

The most common medications for the treatment of this condition include:

The potential complications vary based on the treatment and medication in question. The underlying cause or type of constrictive pericarditis are also factors in complications. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you about the potential side effects or complications, especially when it comes to medications. That’s because your provider can tailor the information to your specific situation and circumstances. They can also tell you what to watch for, how to manage these potential problems and what you can do to try and avoid them entirely.

Potential complications from surgery include:

Because testing and imaging are necessary to diagnose constrictive pericarditis, it isn’t something you should treat or manage yourself. This is especially important because some of the symptoms of this condition also happen with life-threatening conditions like cardiac tamponade or heart attack. Because of that, you should first talk to a healthcare provider and get guidance from them on what you can do for this condition.

Advertisement

Depending on the cause of this condition and the treatments you receive, it may take days or weeks for you to feel better. If you have surgery, the time it takes for you to feel better also needs to take into account how long you’ll need to recover from the surgery itself. Most people will feel better within three months, but some people may need several months to make a full recovery.

The outlook for this condition depends on the cause, the severity of your case, the treatments involved and any other health conditions you might have. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what to expect from this condition and your likely outlook.

Because this condition often happens alongside or because of severe or deadly conditions, the outlook is often negative. This is especially true when it happens because of radiation therapy or when you also have:

Because of the risks, the best outcomes usually happen with early diagnosis and treatment. Good outcomes are also more likely with the transient type of this condition. Even so, about 5% to 10% of those who undergo surgery don’t survive (hospitals that specialize in heart care tend to have better outcomes).

However, most people recover and do well. Nearly 80% of the people who have surgery for this condition live at least five years, and nearly 60% live at least 10 years.

How long this condition lasts depends on the type, cause and treatments you receive. In some cases, this condition goes away on its own or with medication only. That usually takes a few weeks to a few months. The more severe the case or cause, the longer it usually takes for you to recover.

Constrictive pericarditis happens unpredictably, so it’s not possible to prevent it. The only thing you can do to reduce your risk of developing this condition is to avoid situations that might lead to developing it. One example is getting bacterial infections treated quickly rather than delaying care. Another is for medical personnel to limit radiation damage to your pericardium if you receive radiation therapy.

If you have this condition, it's important to follow their guidance on caring for yourself. This includes the following:

Most people will need to see their provider regularly as they recover from this condition. If your condition improves, your provider will likely recommend reducing how frequently you see them.

You should call your healthcare provider or schedule an appointment if you notice that your symptoms are returning or have symptoms that start to change and affect your usual activities and routine.

Many of the symptoms of this condition also happen with life-threatening medical emergencies. Because of that, you should get medical care immediately if you have any of the following symptoms:

Constrictive pericarditis is an uncommon condition that happens unpredictably. It also shares symptoms with many other conditions, so sometimes it can be tough to diagnose. Fortunately, advances in medical knowledge and technology mean it’s easier to diagnose this condition with certain imaging tests. The treatments for this condition have also made great strides. That means that this condition is treatable in most cases, and in some cases, a cure is possible.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Whether your pericardial disease comes on acutely without warning or is chronic, Cleveland Clinic has the best treatments for this heart condition.