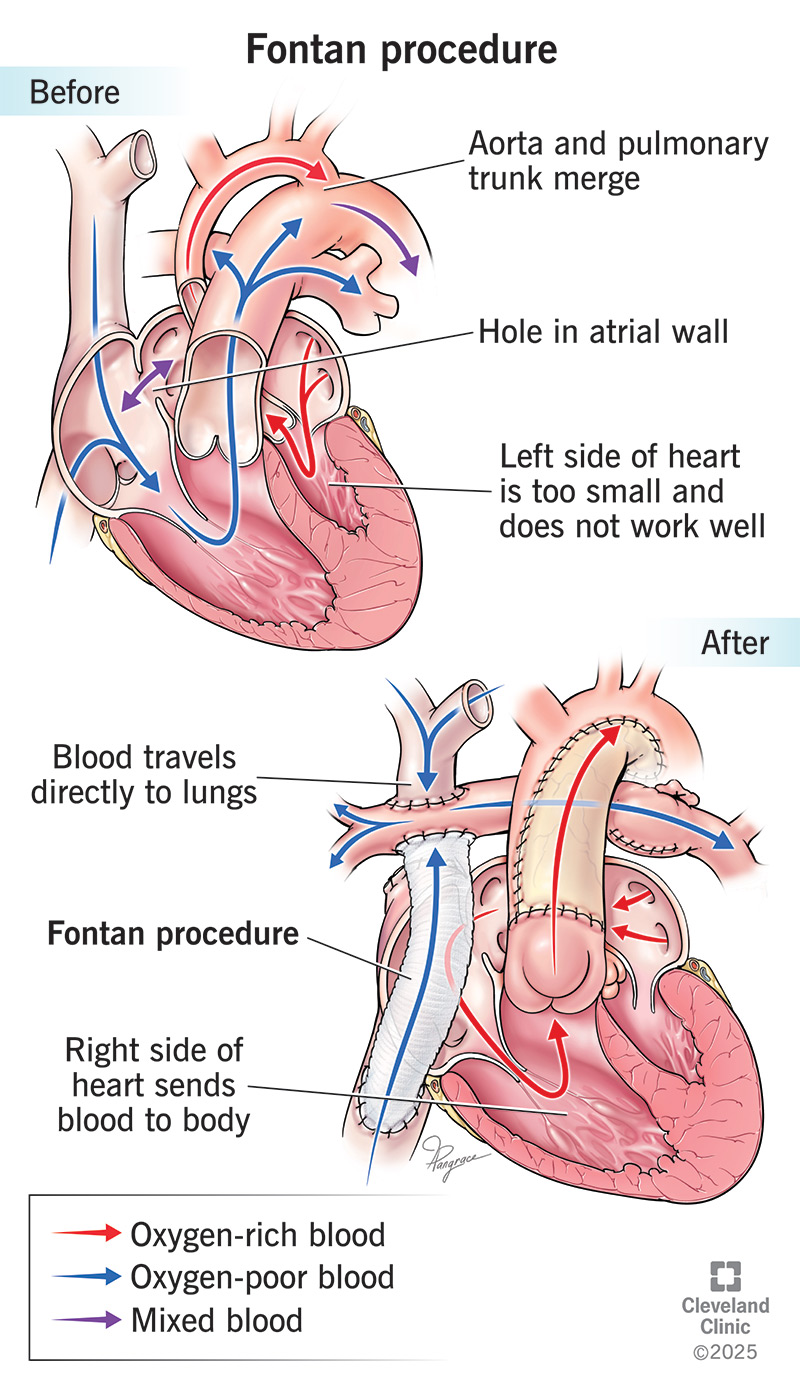

A Fontan procedure is an operation for children who are born with one working heart ventricle. After having a Fontan procedure, all oxygen-poor blood in your child’s body goes straight to their pulmonary artery instead of through their heart chambers. Most people live another 30 years or more after surgery.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/24545-fontan-procedure)

A Fontan procedure is a heart surgery. It helps children born with only one working heart ventricle.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Usually, your heart has two ventricles. One sends blood to your lungs to get oxygen. The other sends oxygen-rich blood to the rest of your body. If one ventricle doesn’t form correctly, the other has to do both jobs. That makes your heart work harder.

A Fontan procedure creates a new path for blood to reach your child’s lungs. It sends oxygen-poor blood from their lower body straight to their lungs (via their pulmonary artery). This blood doesn’t pass through their heart. It takes a kind of shortcut to avoid heavy traffic. This way, the working ventricle can focus on pumping oxygen-rich blood to their body.

This surgery is the last of several procedures to help blood reach the lungs. Most children need one or more earlier surgeries first. These may include the:

A Fontan procedure can treat several issues with how your heart forms before birth, like:

Advertisement

Each year, healthcare providers in the U.S. perform about 1,000 Fontan procedures.

Around 50,000 to 70,000 people worldwide have had this surgery.

Children with a single ventricle issue may need a Fontan procedure between ages 2 and 15, most often between 2 to 5. But this surgery isn’t right for everyone.

Your child’s healthcare provider will check to be sure the Fontan procedure is a good option. For example, their working ventricle must be strong enough to pump well. And their lungs must be healthy enough to handle blood flow without a pump.

Before a Fontan operation, your child will have tests, such as:

In the operating room:

Sometimes, a surgeon does other heart repairs during the same surgery. These may include fixing a valve or widening the opening between heart chambers.

A Fontan surgery can take four to five hours. During that time, your child’s healthcare team will check in with you often and keep you updated.

A Fontan operation makes the heart’s job easier. It improves oxygen levels by keeping oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood from mixing as much.

Short-term complications of a Fontan procedure may include:

Possible long-term Fontan procedure complications include:

No, but it’s common for Fontan patients to need heart transplants 15 to 20 years after a Fontan operation. Over time, your child’s heart may not pump as well or the Fontan circulation may cause progressive liver damage. This is called a “failed Fontan.” This is when your child may need a heart transplant or a combined heart-liver transplant.

One study found that 1 out of 10 adults needed a heart transplant after Fontan surgery.

Advertisement

Your child’s healthcare team will take them to an intensive care unit (ICU) to watch them closely. Next, they’ll go to a regular hospital room.

Before you go home, your care team will tell you how to care for your child.

Most children who have a Fontan operation stay in the hospital for seven to 13 days. The first few days are in the ICU.

After your child’s Fontan procedure, call their provider if they have:

Your child should see their provider every six to 12 months. They may also need regular heart and liver tests.

Sometimes, yes. People without complications may be able to have children. But there is a higher risk of bleeding, pregnancy loss (miscarriage), preterm birth and other issues. Always get a full heart check-up before trying to get pregnant.

Life expectancy depends on the condition people have at birth. Most people are alive 10 years after Fontan surgery. And more than 8 out of 10 people live 30 years or longer.

In fact, many people who’ve had a Fontan procedure live into their 40s and longer.

Survival rates are lowest for people with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Learning that your child has a serious heart condition and needs a Fontan procedure can bring a wave of emotions. It’s normal to feel scared, overwhelmed or unsure of what comes next. We want you to know: You’re not alone.

Advertisement

A Fontan procedure isn’t a cure, but it can help your child’s heart work more efficiently. Many children who’ve had this surgery go on to play, learn, grow and thrive. They may tire more easily or need extra care and check-ups, but with the right support, they can live full lives.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your heart needs some help, the cardiology experts at Cleveland Clinic are here for you. We diagnose and treat the full spectrum of cardiovascular diseases.