Coronary artery disease (CAD) limits blood flow in your coronary arteries, which deliver blood to your heart muscle. Cholesterol and other substances make up plaque that narrows your coronary arteries. Chest pain is the most common CAD symptom. CAD can lead to a heart attack, abnormal heart rhythms or heart failure. Many treatments are available.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

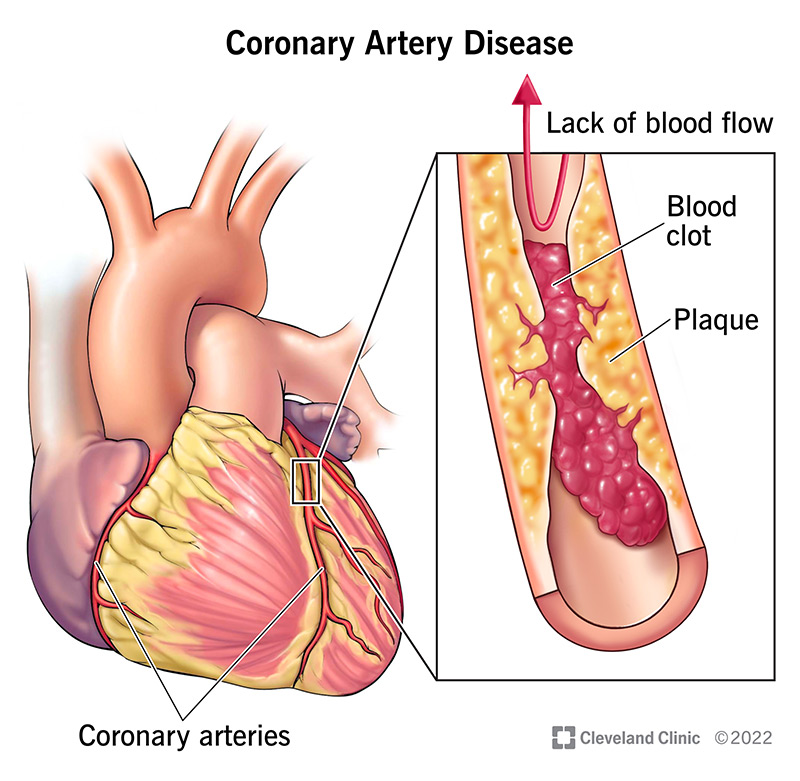

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a narrowing or blockage of your coronary arteries, which supply oxygen-rich blood to your heart. This happens because, over time, plaque (including cholesterol) buildup in these arteries limits how much blood can reach your heart muscle.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Picture two traffic lanes that merge into one due to construction. Traffic keeps flowing, just more slowly. With CAD, you might not notice anything is wrong until the plaque triggers a blood clot. The blood clot is like a concrete barrier in the middle of the road. Traffic stops. Similarly, blood can’t reach your heart, and this causes a heart attack.

You might have CAD for many years and not have any symptoms until you experience a heart attack. That’s why CAD is a “silent killer.”

Other names for CAD include coronary heart disease (CHD) and ischemic heart disease. It’s also what most people mean when they use the general term “heart disease.”

There are two main forms of coronary artery disease:

Coronary artery disease is very common. Over 18 million adults in the U.S. have coronary artery disease. That’s roughly the combined populations of New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago and Houston.

Advertisement

In 2021, coronary artery disease killed 375,500 people in the U.S.

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. and around the world.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/16898-coronary-artery-disease)

You may have no symptoms of coronary artery disease for a long time. Plaque buildup takes many years, even decades. But as your arteries narrow, you may notice mild symptoms. These symptoms mean your heart is pumping harder to deliver oxygen-rich blood to your body.

Symptoms of chronic CAD include:

Sometimes, the first coronary artery disease symptom is a heart attack.

Atherosclerosis causes coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis is the gradual buildup of plaque in arteries throughout your body. When the plaque affects blood flow in your coronary arteries, you have coronary artery disease.

Plaque consists of cholesterol, waste products, calcium and fibrin (a substance that helps your blood clot). As plaque collects along your artery walls, your arteries become narrow and stiff.

Plaque can clog or damage your arteries, which limits or stops blood flow to a certain part of your body. When plaque builds up in your coronary arteries, your heart muscle can’t receive enough blood. So, your heart can’t get the oxygen and nutrients it needs to work properly (myocardial ischemia). It leads to chest discomfort (angina) and puts you at risk of a heart attack.

People who have plaque buildup in their coronary arteries often have buildup elsewhere in their body, too. This can lead to conditions like carotid artery disease and peripheral artery disease (PAD).

Partly. Family history affects your risk of coronary artery disease, but many other risk factors have nothing to do with your genetics. The choices you make every day add up to a big impact on your risk of CAD.

There are many risk factors for coronary artery disease. You can’t change all of them, but you can manage some of them by making lifestyle changes or taking medications. Talk with your provider about what you can do about these risk factors:

Advertisement

The main complication of coronary artery disease is a heart attack. This is a medical emergency that can be fatal. Your heart muscle starts to die because it’s not receiving enough blood. You need prompt medical attention to restore blood flow to your heart and save your life.

Over the years, CAD can also weaken your heart and lead to complications, including:

Healthcare providers diagnose coronary artery disease through a physical exam and testing.

During your physical exam, your provider will:

All of this information will help your provider determine your risk for heart disease.

Your provider may also recommend one or more tests to assess your heart function and diagnose CAD. These include:

Advertisement

Coronary artery disease treatment often includes lifestyle changes, risk factor management and medications. Some people may also need a procedure or surgery.

Your healthcare provider will talk with you about the best treatment plan for you. It’s important to follow your treatment plan so you can lower your risk of serious complications from CAD.

Lifestyle changes play a big role in treating coronary artery disease. Such changes include:

Be sure to talk with your provider before starting any new exercise program. Your provider can also offer guidance on lifestyle changes tailored to your needs. They may recommend smoking cessation options or meeting with a dietitian to discuss healthy eating plans.

Managing your risk factors for CAD can help slow down the progression of your disease. Work with your provider to manage the following conditions:

Advertisement

Medications can help you manage your risk factors and treat symptoms of coronary artery disease. Your provider may prescribe one or more medications that:

Some people need a procedure or surgery to manage coronary artery disease, including:

Complications or side effects of coronary artery disease treatments may include:

After PCI (angioplasty), you can usually get back to normal activities within a week. After CABG (bypass surgery), you’ll be in the hospital for more than a week. After that, it’ll take six to 12 weeks for a full recovery.

Your provider is the best person to ask about your prognosis. Outcomes vary based on the person. Your provider will look at the big picture, including your age, medical conditions, risk factors and symptoms. Lifestyle changes and other treatments can improve your chances of a good prognosis.

You can’t reverse coronary artery disease. But you can manage your condition and prevent it from getting worse. Work with your healthcare provider and follow your treatment plan. Doing so will give you the strongest possible chance of living a long and healthy life.

You can’t always prevent coronary artery disease because some risk factors are out of your control. But you can lower your risk of coronary artery disease and help prevent it from getting worse in these ways:

The most important thing you can do is keep up with your treatment plan. This may include lifestyle changes and medications. It may also involve a procedure or surgery and the necessary recovery afterward.

Along with treatment, your provider may recommend cardiac rehab. A cardiac rehab program is especially helpful for people recovering from a heart attack or living with heart failure. Cardiac rehab can help you with exercise, dietary changes and stress management.

A CAD diagnosis may make you think about your heart and arteries more than ever before. This can be exhausting and overwhelming. You may worry a lot about your symptoms or what might happen to you. Many people with coronary artery disease experience depression and anxiety. It’s normal to worry when you’re living with a condition that can be life-threatening.

But the worry shouldn’t consume your daily life. You can still live an active, fulfilling life while having heart disease. If your diagnosis is affecting your mental health, talk with a counselor. Find a support group where you can meet people who share your concerns. Don’t feel you need to keep it all inside or be strong for others. CAD is a life-changing diagnosis. It’s OK to devote time to processing it all and figuring out how to feel better, both physically and emotionally.

Your provider will tell you how often you need to come in for testing or follow-ups. You may have appointments with specialists (like a cardiologist) in addition to your primary care visits.

Call your provider if you:

Call 911 or your local emergency number if you have symptoms of a heart attack or stroke. These are life-threatening medical emergencies that require immediate care. It may be helpful to print out the symptoms and keep them where you can see them. Also, share the symptoms with your family and friends so they can call 911 for you if needed.

If your provider hasn’t diagnosed you with coronary artery disease, consider asking:

If you have coronary artery disease, some helpful questions include:

Learning you have coronary artery disease can cause a mix of emotions. You may feel confused about how this could happen. You may feel sad or wish you’d done some things differently to avoid this diagnosis. But this is a time to look forward, not backward. Let go of any guilt or blame you feel. Instead, commit to building a plan to help your heart, beginning today.

Work with your provider to adopt lifestyle changes that feel manageable to you. Learn about treatment options, including medications, and how they support your heart health. Tell your family and friends about your goals and how they can help you. This is your journey, but you don’t have to do it alone.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When you need treatment for coronary artery disease, you want expert care. At Cleveland Clinic, we’ll create a treatment plan that’s personalized to you.