Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a weakness of your heart muscle that doesn’t come from any other cause. It happens in the last month of pregnancy or within five months after delivery. This condition leads to heart failure and can be fatal. Symptoms include fatigue, heart palpitations and shortness of breath.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/23220-peripartum-cardiomyopathy)

Peripartum cardiomyopathy is a rare condition that weakens your heart muscle. This lowers your heart’s ability to pump blood to the rest of your body, which can be life-threatening. This condition affects women in the last month of pregnancy or up to five months after delivery. For that reason, people also call it postpartum cardiomyopathy or pregnancy-associated cardiomyopathy. It can happen at any age but is most common in those older than 30.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

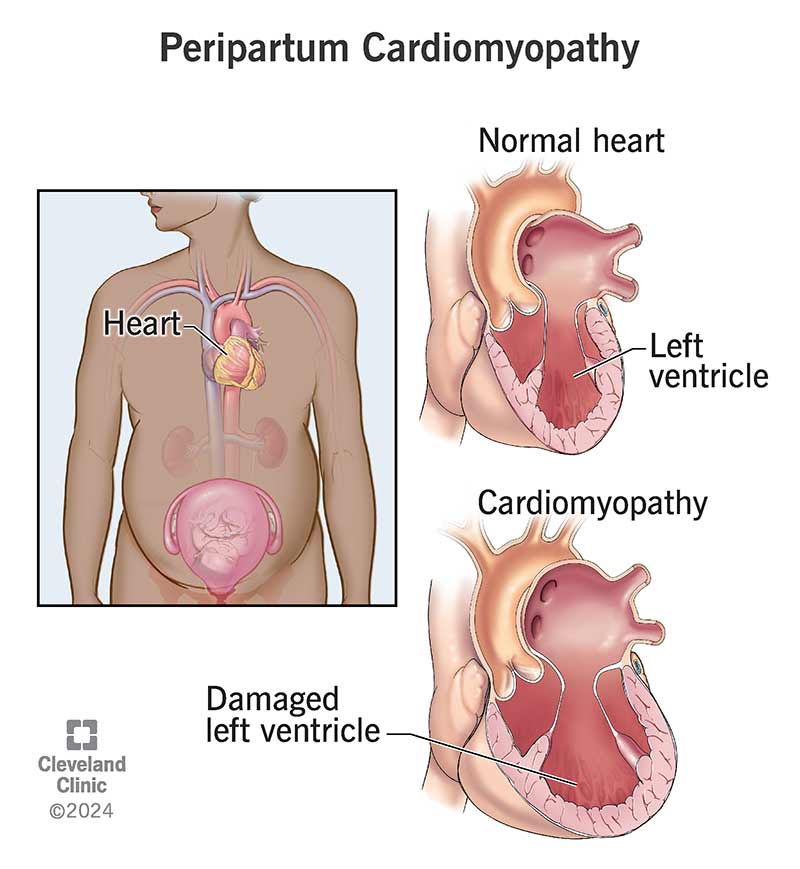

Peripartum cardiomyopathy damages one of the chambers of your heart, the left ventricle, and makes it less able to do its job. Your left ventricle has the important job of pumping oxygen-rich blood throughout your body.

You might hear your healthcare provider use the term “left ventricular ejection fraction” (LVEF). They usually check this with an echocardiogram. LVEF refers to how well your left ventricle can pump blood out of your heart. Providers describe your LVEF as a percentage, and a higher number is better. Normally, your LVEF is 50% to 70%. Peripartum cardiomyopathy reduces your LVEF to less than 45%. The lower your LVEF, the more serious your condition.

An early diagnosis is key for getting proper treatment and greatly increases your chances of a smooth recovery.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy isn’t common, but it’s hard to say exactly how rare it is. Estimates vary widely both in the U.S. and globally.

In the U.S., peripartum cardiomyopathy affects between 1 in 1,000 and 1 in 4,000 pregnancies. Estimates show it’s more common in the southern U.S. than in other regions.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy symptoms are easy to miss because many of them are like what you feel during pregnancy. But because the condition is so serious, it’s important to watch for the following symptoms:

Advertisement

Peripartum cardiomyopathy usually begins in the last month of pregnancy or later. But it can start sooner. It's also possible for pregnancy to put extra strain on your heart and make a previously undiagnosed heart condition worse. So, it’s important to track symptoms throughout your pregnancy, not just in the final weeks.

Researchers don’t know what causes peripartum cardiomyopathy. But they think possible causes include hormonal changes during pregnancy and other conditions like preeclampsia. Several factors may combine to cause this condition.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy may be hereditary (passed from parents to their biological children), but research hasn’t proven this link yet. About 15% to 20% of women with peripartum cardiomyopathy have genetic mutations that can cause cardiomyopathy. If you have this genetic mutation, the stress of pregnancy and delivery might trigger cardiomyopathy symptoms. It’s important for you and your cardiologist to know of any history of heart diseases, specifically cardiomyopathy or heart failure, in your biological family.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy has many risk factors. The more risk factors you have, the more likely you are to develop peripartum cardiomyopathy. The risk factors add up to pose an even greater threat than one would on its own.

Risk factors before pregnancy

Risk factors related to pregnancy

Complications during pregnancy

Special considerations for Black women

Research has shown that Black women:

Advertisement

As your left ventricle gets weak and tired, it can’t pump blood as efficiently to your lungs, liver and other organs that rely on it. This slowdown affects your whole body. It leads to heart failure and raises your risk of blood clots and thrombosis.

Life-threatening complications may include:

Your provider will diagnose you with peripartum cardiomyopathy if you meet all three of these criteria:

To reach a diagnosis, your provider will talk with you about your health history and family history.

When making a diagnosis, your provider may refer to your condition as a Class I, II, III or IV. The higher the number, the more severe your condition. An early diagnosis reduces your risk of dying from peripartum cardiomyopathy and allows you to get treatment as soon as possible. If you get a diagnosis after the condition gets worse, you’re more likely to have serious complications like continued heart problems.

Advertisement

There’s no specific test for diagnosing peripartum cardiomyopathy. Instead, your provider will use other tests along with the information you give them. They’ll perform a physical exam to look for signs of extra fluid in your body. Then, you’ll have tests that may include:

These tests will reveal any heart problems that you had before your pregnancy. Some people have heart problems for years and don’t know until they start having symptoms during pregnancy. Your test results will help your provider make an accurate diagnosis.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy treatment manages heart failure symptoms and helps your heart recover. The condition doesn’t go away on its own. If you get a diagnosis during pregnancy, your provider will make sure any medications are safe for the fetus. They’ll talk with you about treatment options and discuss possible side effects. You’ll also likely work with a team of specialists who can offer advice on high-risk pregnancy and the impact of heart disease on pregnancy.

Advertisement

You’ll probably need medications that also treat other types of heart failure, like:

Depending on how well your heart is functioning, you may need other treatments, like:

Side effects vary based on the treatment and whether you’re pregnant at the time. Taking beta-blockers during pregnancy may cause your baby to have a smaller birth weight or conditions like hypoglycemia, bradycardia or heart block.

Some medicines — including ACE inhibitors, ARBs, ARNIs, MRAs and SGLT2 inhibitors — aren’t safe to use during pregnancy. But they’re generally safe to use while breastfeeding since only small amounts pass into your breast milk. It’s important to talk with your provider about the timing, risks and side effects of each medication.

More than 50% of people who have peripartum cardiomyopathy recover to have a typical heart function — often with less than six months of treatment. For some, it only takes a few days or weeks. Others may need years to recover.

But you’ll likely need to keep taking medicine for at least a year after your heart function recovers.

If you have peripartum cardiomyopathy, you’ll work closely with your healthcare provider and a team of specialists to monitor your health. If you’re still pregnant, your health team will monitor the condition of your fetus, too.

They’ll also create a plan for your type of delivery. If your heart failure is stable, your provider will likely prefer you have a vaginal delivery. But you may need an epidural, episiotomy or the use of forceps to make delivery easier.

If you have peripartum cardiomyopathy, you're more likely to have a Cesarean delivery (C-section) or preterm birth. It’s important to know your options and risks and talk about them with your provider.

After delivery, you’ll continue to work with your provider to manage your care and treatment. How you feel and how quickly you recover depend on many factors, but the most important factor is your left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). If your LVEF is less than 30% at diagnosis, you’re at a higher risk of serious complications.

For some people, peripartum cardiomyopathy becomes permanent. For others, treatment can manage the symptoms and restore some or all heart function.

If your LVEF reaches at least 50% to 55%, a provider considers that a full recovery from peripartum cardiomyopathy. Most studies check this number six months after diagnosis. Recovery varies widely by region and ethnicity. Recovery rates in the U.S. range from 44% to 63% after six months, while recovery rates in some countries are just 21% to 36%.

One study found that 4 in 5 Black women don’t fully recover from peripartum cardiomyopathy, and 1 in 10 don’t survive.

You’ll have to monitor your health and work closely with your healthcare provider, even after your heart function returns to normal. That’s because 1 in 5 women who recover from peripartum cardiomyopathy have a heart failure relapse later. Also, even after your LVEF returns to a healthy level, you may still feel long-term effects like reduced exercise capacity.

Life expectancy with peripartum cardiomyopathy depends on your condition, how well the treatment works and many other factors related to your overall health. Your risk of dying is higher with a lower ejection fraction (LVEF). Also, the outlook isn’t as good for those who need medical devices to help their hearts function.

Researchers estimate the mortality rate is between 2.5% and 32% globally. The U.S. sits at the lower end with a mortality rate between 6% and 10%.

The best way to prevent peripartum cardiomyopathy is to do whatever you can to keep your heart healthy. While you can’t avoid all of your risk factors, you can manage others by:

If you had heart failure during a previous pregnancy, talk with your healthcare provider about your risk factors if you’re planning to get pregnant again.

The most important thing you can do to take care of yourself is to visit your healthcare provider regularly. Follow your provider’s plan and call your provider to talk about any problems or changes you notice.

Some simple daily changes you can make may include:

If you’re breastfeeding, talk with your provider about any risks, like passing medicine to your baby through breast milk. Usually, the benefits of breastfeeding — like bonding with your baby — outweigh the risks. You may want to work with a post-pregnancy counselor to decide what’s best for you and your baby.

Peripartum cardiomyopathy can be a life-changing diagnosis. You may feel a range of emotions, all while you’re bonding with and caring for your baby. It’s a lot to handle at once.

Stress from peripartum cardiomyopathy raises your risk of developing mood disorders. More than 50% of people with peripartum cardiomyopathy develop generalized anxiety or anxiety over the condition of their heart.

While about 1 in 10 postpartum women in the U.S. have postpartum depression, about 1 in 3 women develop depression after a peripartum cardiomyopathy diagnosis.

If you feel upset, confused or overwhelmed, you’re not alone. If you aren’t already working with a counselor or therapist, ask your provider to recommend one.

If you have any symptoms of peripartum cardiomyopathy, call your healthcare provider right away. You’ll have regular appointments during treatment. Once your heart is working well again (with a normal LVEF), you’ll need a provider to check your heart once a year or more often. This allows them to check to make sure the condition doesn’t return. If it does, they can catch it early with regular checkups.

If you have chest pain, heart palpitations, fainting or any new symptoms, call 911 (or your local emergency service number) or go to the ER.

Questions to ask your healthcare provider may include:

For many women, peripartum cardiomyopathy happens more than once. If you have it with one pregnancy, you’re more likely to have it again. About 1 in 3 women will develop it with a later pregnancy.

You can talk with your healthcare provider about whether it’s safe to have another pregnancy. If it’s too risky, you may want to explore options for birth control. You’ll need contraception that doesn’t contain estrogen because estrogen therapies raise your risk of blood clots and thrombosis.

If you do have another pregnancy, you’ll need close monitoring and regular checkups to catch any early signs of heart failure.

When you’re preparing to have a baby, you don’t expect to have a heart issue at the same time. It can be overwhelming to juggle caring for a newborn with managing a heart condition that’s new to you. Your team of healthcare providers will help you every step of the way and do everything possible to help your heart get stronger. If you’re pregnant and have any of the risk factors for peripartum cardiomyopathy, talk with your provider. An early diagnosis is vital for getting you the treatment you need and reducing the risk of serious complications for you and your baby.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your heart needs some help, the cardiology experts at Cleveland Clinic are here for you. We diagnose and treat the full spectrum of cardiovascular diseases.