Turner syndrome happens when your female baby is born with a missing or partial X chromosome. It causes symptoms like short stature, delayed puberty and issues with ovary function. There’s currently no cure. Treatment involves managing hormone levels and other health conditions.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Turner syndrome (TS) is when one of the X chromosomes is partially or completely missing. It’s a congenital condition (meaning, a condition that you’re born with) that affects females only.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

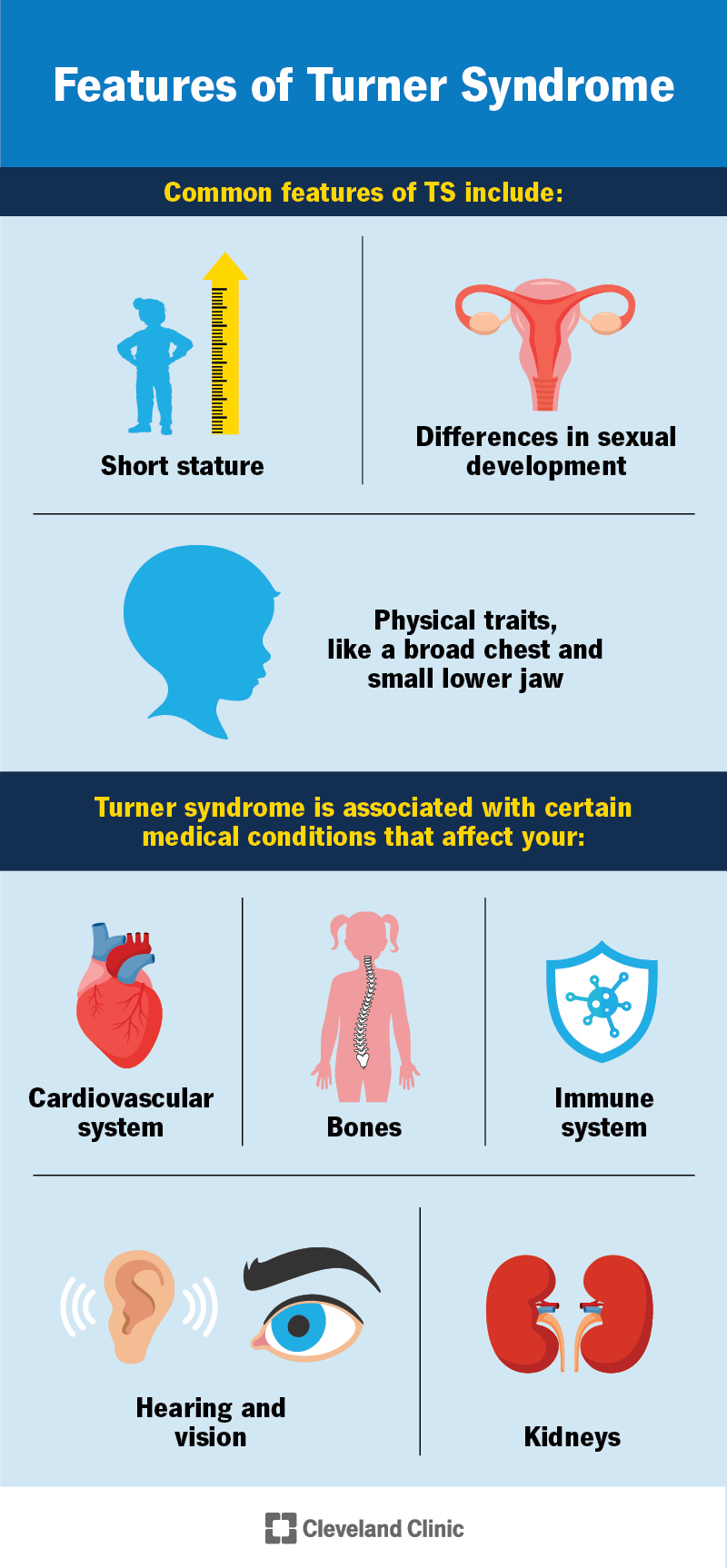

TS affects everyone differently. But short height and low-functioning ovaries are the two most common features of the condition.

The disease may affect 1 in 2,000 to 2,500 infant girls.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/15200-turner-syndrome)

Some girls have noticeable Turner syndrome symptoms early in life, while others might not show signs until later. Symptoms can be mild and develop gradually during childhood. Or they can be significant and noticeable shortly after birth. Still, others don’t receive a diagnosis until adulthood.

Your healthcare provider may suspect TS before birth based on prenatal genetic testing or pregnancy ultrasound. Signs include the fetus having:

Symptoms of TS that appear at birth or shortly after are:

Some of the signs and symptoms of TS in children, teens and adults are:

Advertisement

Almost everyone with Turner syndrome experiences short height and ovaries that don’t work as they should. As TS affects everyone differently, you should talk to your child’s healthcare provider about what symptoms and features to expect or look out for.

Turner syndrome happens when one X chromosome is partially or completely missing in your female child.

Humans typically have 23 pairs of chromosomes, for a total of 46. These include 22 pairs of numbered chromosomes (called autosomes) and one pair of sex chromosomes. You inherit one chromosome of each pair from each biological parent. The 23rd pair determines sex at birth: Typically, females have two X chromosomes (XX), while males have one X and one Y chromosome (XY).

Researchers don’t yet understand why this happens. It could be because of a problem with the egg or sperm at conception or due to a change in the X chromosome during fetal development.

There are two main types. The type depends on whether the X chromosome is completely or partially missing.

People with Turner syndrome are at higher risk for certain health conditions. These can include:

Advertisement

People with Turner syndrome may also have:

Healthcare providers can diagnose Turner syndrome before or after birth.

Before birth, they use the following tests to diagnose the condition:

Advertisement

After birth, a karyotyping test can confirm Turner syndrome. This is a blood test. A pathologist will check your blood for a missing X chromosome.

There’s no cure for Turner syndrome. But certain medications and therapies can help manage symptoms.

Besides caring for related medical problems, treatment often focuses on hormones. Treatments may include:

Early diagnosis and treatment are key. Pay attention to your child’s growth and milestones. Perhaps you noticed your child doesn’t seem to be growing as you expect, or you see unusual physical symptoms. Talk to their pediatrician about your concerns.

Advertisement

Certain treatments, like hormone therapy, are most effective if you start them early. Your child will likely need frequent check-ups to prevent common health complications with TS.

Providers also recommend that children with Turner syndrome:

Turner syndrome affects everyone differently. It’s impossible to predict how it’ll affect your child. The best way you can prepare is to talk to healthcare providers who specialize in Turner syndrome. They can help you navigate the lifelong treatment your child will need.

The life expectancy for people with Turner syndrome might be slightly shorter. But with close monitoring of the health issues that may come with TS, people can usually expect to live a typical lifespan.

Learning that your child has a genetic condition can feel overwhelming. Turner syndrome isn’t preventable, but it’s manageable. Know that you’re not alone — many resources are available to help you and your family. It’s important that you speak with a healthcare provider who’s very familiar with Turner syndrome so you can learn more about what to expect and how to care for your child.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic Children’s expert healthcare providers treat Turner syndrome with care and compassion for your child and your family.