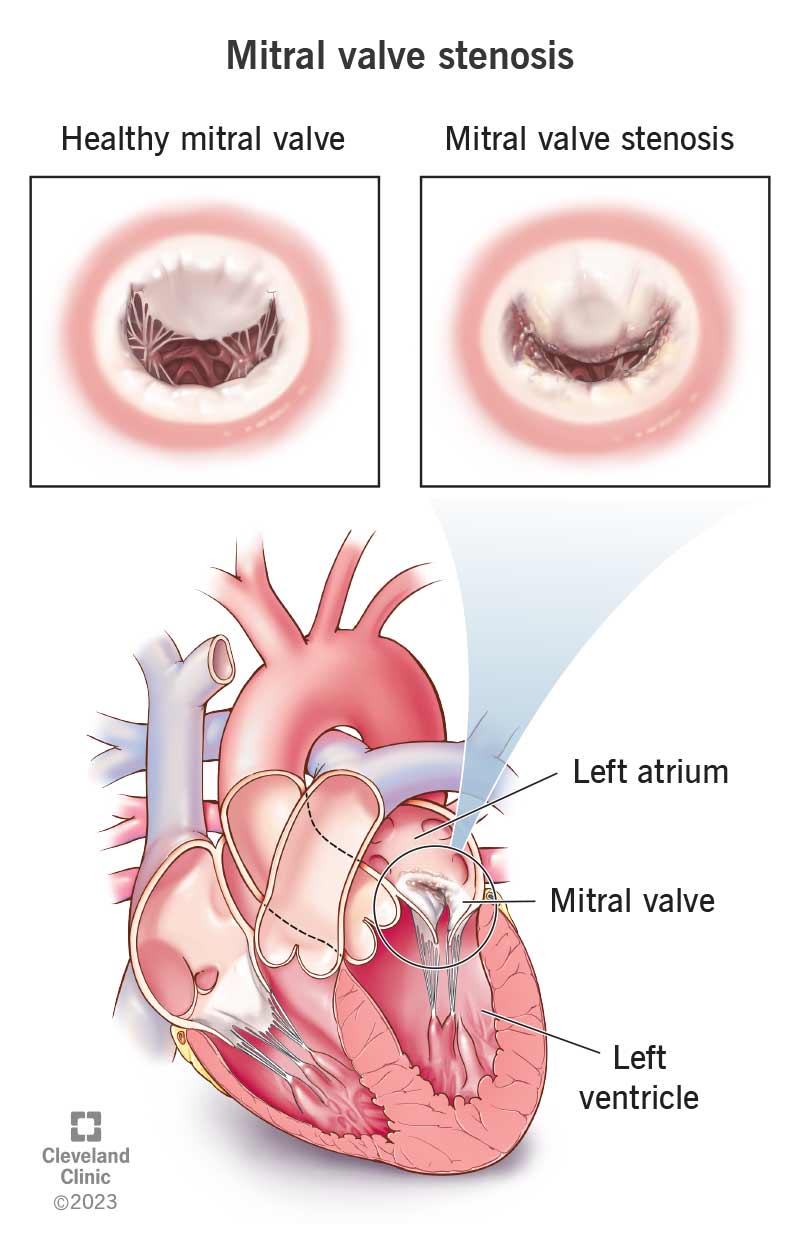

Mitral valve stenosis or mitral stenosis describes a mitral valve opening that’s smaller than normal. This means it can’t let a normal amount of blood move from your upper chamber to your lower chamber (ventricle) on your heart’s left side. Your left ventricle has the important job of pumping oxygen-rich blood to your body.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/21903-mitral-valve-stenosis)

Mitral valve stenosis (sometimes called mitral stenosis) is a narrowing or blockage of the mitral valve inside your heart. Over time, this condition can cause heart rhythm problems and a higher risk of stroke. It may lead to heart failure and death.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A narrow mitral valve makes it harder for blood to flow from the left atrium (upper chamber) to the left ventricle (lower chamber) on the left side of your heart. This is because the valve can’t open as much as it should to let blood go through. It’s like a door that can’t open all the way.

Your mitral valve is the first valve that blood passes through after traveling through your lungs to collect oxygen. Getting blood to your left ventricle is important because it sends oxygen-rich blood to all your body’s cells.

Common causes of mitral valve stenosis include an allergic or immune reaction to a bacterial infection and calcification of the valve. Children can also have mitral valve stenosis when they’re born (congenital). It can also happen late in life.

Mitral valve stenosis is an uncommon disease, especially in developed countries. It affects about 1 out of every 100,000 people in the U.S. It’s more common in developing countries, especially when there’s limited access to antibiotics and medical care.

Mitral valve stenosis is much more likely to happen in females. In developed countries, people in their 50s and 60s make up the majority of mitral valve stenosis cases. In developing countries, it’s a more common diagnosis in younger adults.

Advertisement

When it happens in infants and children, healthcare providers find most cases before the age of 2. It may also run in families, increasing the risk of having it if one of your relatives also has it.

The most common mitral valve stenosis symptoms are:

Children who are born with mitral stenosis often have these symptoms:

If you have mild or moderate mitral valve stenosis, you may not have any symptoms. Many women who have mitral stenosis don’t know it until they develop symptoms during pregnancy. This is because, when you're pregnant, your heart works harder to provide blood for both your needs and those of a fetus.

Mitral valve stenosis causes include:

Advertisement

Mitral valve stenosis risk factors include:

Mitral valve stenosis complications include:

Your primary care provider may detect symptoms of mitral stenosis during a regular checkup and refer you to a specialist. One of the easiest signs of mitral stenosis for a healthcare provider to detect is a heart murmur. Your provider can usually hear a murmur when using a stethoscope to listen to your heart and breathing during a routine physical exam. More severe cases can cause more than one sound as part of the murmur, which can help your provider determine the severity of your case.

A cardiologist will usually do one or more of the following tests to diagnose your case and determine its severity:

Advertisement

Healthcare providers may talk about mitral valve stenosis stages. These range from A to D, with D being the most severe. At each stage, a provider may see irregularities in how your mitral valve looks or functions. Stages C and D have the most severe issues. You don’t have symptoms until stage D.

Mitral valve stenosis treatments can manage — but not cure — your condition. Once you have symptoms, it’s important to get mitral valve stenosis treatment sooner rather than later. By the time symptoms begin, the problem is often past the mild stage.

Some treatments, especially valve repair or replacement, can stop or reduce your symptoms for years. Other treatments, like medication, can also help by preventing complications.

Several different types of medicine (like beta-blockers, diuretics or blood thinners) can treat symptoms of mitral valve stenosis. Some of these drugs also treat or prevent:

Your provider may also prescribe a long-term course of antibiotics to prevent heart valve damage.

For these procedures, a healthcare provider inserts a catheter into an artery in your body. They advance the catheter up to your heart and use it to repair or replace your valve.

Advertisement

A surgeon can use many different methods for mitral valve repair, including minimally invasive surgery or robotically assisted surgery. People with mitral valve stenosis from rheumatic heart disease may have a commissurotomy. This separates the areas where your valve’s flaps fused together or got too thick.

Depending on your case and your needs, your surgeon may recommend either repairing the valve or replacing it altogether. Your new valve may contain animal tissue, artificial materials or both. Your provider can help you choose the best option.

Complications of mitral valve stenosis treatment may include:

Recovery time for mitral valve stenosis repair or replacement procedures depends on the method. Surgical methods take the longest. You may need to stay in the hospital for days, and it may be weeks before you recover fully.

Methods that use a catheter-based approach have much faster recovery times. Most people can go home either the same day or the next day and recover fully in days or a few weeks.

It can take years or even decades before mitral valve stenosis symptoms develop, especially when rheumatic fever is the cause. Many people don’t develop mitral valve stenosis for 20 to 40 years after they first had rheumatic fever.

Once you develop symptoms, the progression of the disease usually speeds up. Your prognosis depends on how active/functional you are at baseline. People with more severe symptoms like shortness of breath have a worse prognosis than those without. For people who’ve developed high blood pressure in their lungs because of mitral valve stenosis, that survival time is around three years. Heart failure is common in advanced cases.

For children born with mitral valve stenosis, the outlook strongly depends on the severity of their case. Many people born with mitral valve stenosis may need screening for related heart problems for the rest of their lives.

The best outcomes from mitral valve stenosis happen with early detection and timely treatment. Because mitral valve stenosis usually causes a heart murmur, your healthcare provider can often catch it when they listen to your heart during an annual physical exam or checkup. This can help detect and treat it before it becomes severe or advanced.

In many cases, yes. Treating bacterial infections can prevent many cases of mitral valve stenosis. Most cases happen because of unrecognized — and therefore untreated — bacterial infections. Don’t wait to treat a bacterial infection like strep throat or scarlet fever. Follow your healthcare provider’s instructions closely. Take any prescribed antibiotics and other medications according to the instructions — and not just until you feel better.

You usually can’t prevent mitral stenosis that happens because of aging. However, you may be able to delay when it happens by exercising regularly, maintaining a weight that’s healthy for you, eating a healthy diet and getting an annual checkup.

You can’t prevent the kind of mitral stenosis that you’re born with.

Your healthcare provider can help guide you through what you can do to manage mitral valve stenosis. They may recommend:

If you develop the symptoms of mitral valve stenosis, especially ones that disrupt your life, you should contact your healthcare provider.

After starting a new medication, you should go to the ER if you:

After a surgery or catheter procedure, you should go to the ER if:

Questions to ask your provider may include:

It can be troubling to learn that a part of your heart isn’t working as well as it should be. But take heart. Finding mitral valve stenosis early and treating it gives you a better outlook. Your healthcare provider can choose from many treatments that can help. Talk with them about which one is right for your situation.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Problems with your heart can be scary. Our experts can diagnose and treat mitral & tricuspid heart valve disease.