A thoracic aortic aneurysm is a bulge in the part of your aorta that runs through your chest. It forms when your aorta wall grows weak from plaque, connective tissue disorders or other factors. You may feel no symptoms until the aneurysm causes a medical emergency. A healthcare provider can evaluate your risk and help you stay healthy.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17552-thoracic-aoritc-aneurym-illustration)

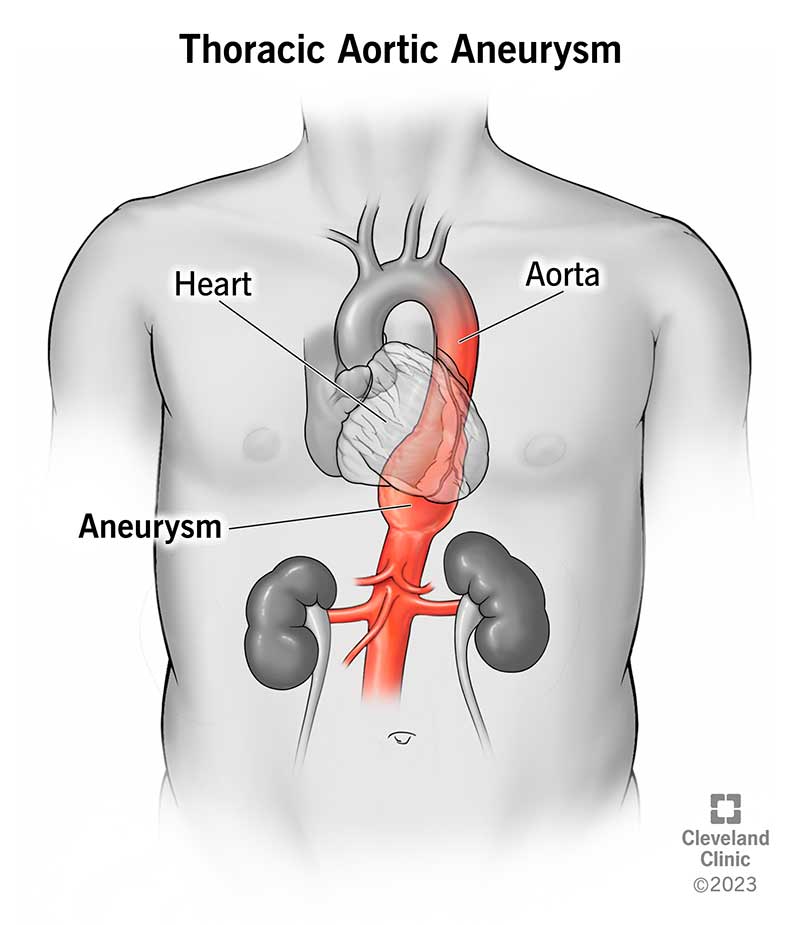

A thoracic aortic aneurysm is a bulge that develops in the part of your aorta that extends through your chest (thorax). You might hear it described as an expansion, ballooning or widening of your aorta. All of these words describe how an aneurysm disrupts the aorta’s normal, tube-like shape. A widened portion of your aorta qualifies as an aneurysm if it’s at least 50% wider than the normal aortic diameter. The precise “normal” size changes depending on the location.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

An aneurysm can form anywhere along your aorta. Most form in the belly (abdominal aortic aneurysm), but about 1 in 4 form in the chest.

Small aneurysms may only need conservative treatment. This includes medications to manage underlying conditions and regular imaging tests. But if your aneurysm is larger or growing fast, you may need surgery to lower your risk of potentially fatal complications. Healthcare providers tailor treatment (and its timing) to your needs to give you the best chance of a good outcome.

Thoracic aortic aneurysms affect about 6 to 10 in every 100,000 people. Researchers don’t know the exact number since many of these aneurysms cause no symptoms and may go undiagnosed. About 20% of known cases occur in people with a family history of the condition.

Ruptured aortic aneurysms and dissections lead to about 30,000 deaths per year in the U.S.

Thoracic aortic aneurysms often go unnoticed because people rarely feel symptoms. Possible warning signs include:

Advertisement

Many people have no symptoms until the aneurysm ruptures (bursts) or dissects (tears).

Thoracic aortic aneurysm ruptures and dissections are medical emergencies. Their symptoms usually start abruptly and are severe. Seek care immediately if you have:

Your chance of surviving goes down with each hour (even minute) that passes. Don’t wait to seek care for yourself or someone else with these symptoms.

Atherosclerosis is the most common cause of thoracic aortic aneurysms. That’s because plaque buildup weakens your aorta’s walls over time, making aneurysms more likely to develop.

Your aorta’s walls should normally be strong and flexible enough to expand and contract as blood flows through. Your aorta receives blood directly from your heart. So, it must withstand the constant pressure of your heart’s forceful pumping action.

A healthy aorta can do this just fine. But if your aorta’s walls are weak, the pressure can cause a section of your aorta to expand outward and form a bulge (aneurysm). This aneurysm is abnormal and disrupts your aorta’s tube-like shape. Blood continues to flow through this section, but the constant pressure on the already weak walls makes them even weaker. As a result, the walls expand even further. The larger an aneurysm gets, the more dangerous it becomes.

Anything that weakens your aorta’s walls can raise your risk for aneurysm formation. Besides atherosclerosis, known risk factors include:

Yes, thoracic aortic aneurysms can run in families. Researchers have identified several genetic mutations that raise a person’s risk. Among these, mutations to the ACTA2 gene are the most common.

The ACTA2 gene tells your body how to make certain proteins in your artery walls. These proteins help your artery walls keep their shape despite the constant pressure of blood flow. An ACTA2 mutation can cause your aorta’s walls to stretch out farther than they should when blood pushes through.

Just because you inherit a gene mutation doesn’t mean you’ll develop an aneurysm. But you face a higher risk. If a thoracic aortic aneurysm has affected a close biological family member, talk to a healthcare provider. They may recommend genetic testing.

Thoracic aortic aneurysms form in areas where your artery walls are weak. Factors like plaque buildup or connective tissue diseases can weaken your aorta’s walls and make them vulnerable to aneurysm formation.

Advertisement

Your aorta is the largest artery in your body, and it’s shaped like an old-fashioned walking cane. It curves upward from your heart, forms an arch, and then curves downward through your chest and belly. It ends near your belly button.

Most thoracic aortic aneurysms form in your ascending aorta (the part that curves upward from your heart) or your descending aorta (the part that extends downward through your chest). Less often, they form in your aortic arch, which is the curved part at the top that resembles the handle of a cane.

A thoracic aortic aneurysm is a serious medical condition. Possible complications include:

Thoracic aortic aneurysms are often an incidental diagnosis. This is a medical term that means healthcare providers find a condition through tests they’ve ordered for other reasons. In this case, a chest X-ray may show your mediastinum (the middle part of your chest) is wider than normal. This can be a sign of an aneurysm.

If your provider suspects you have a thoracic aortic aneurysm due to chest X-ray findings or other reasons, they’ll order tests, such as:

Advertisement

Aorta surgery is the definitive way to treat thoracic aortic aneurysms. Providers use many different surgical approaches, including:

Surgeons sometimes combine approaches (such as open surgery and endovascular methods) depending on the nature of the aneurysm. Seeking care at an aorta center that specializes in treating aortic disease can give you the most options and improve your outcome.

Advertisement

Your provider will determine if and when you need surgery based on the following factors:

If the aneurysm is large or causing symptoms, you’ll need prompt surgery to prevent it from rupturing. Aneurysm size matters because the larger an aneurysm gets, the more likely it is to rupture. In general, providers decide it’s time for surgery if your aneurysm is 2 to 2.2 inches wide, or if it’s growing about a half-centimeter in diameter each year.

But size isn’t the only factor. Your provider may want to operate sooner if you have a connective tissue disorder, a bicuspid aortic valve or other factors that raise your risk for rupture or dissection. Talk to your provider about the size of your aneurysm and when you might need surgery.

If the aneurysm is small and not causing symptoms, you may not need surgery right away. Instead, your provider will monitor your condition (“watchful waiting”). They’ll also prescribe medications to lower your risk for complications.

For example, they’ll order imaging scans every six to 12 months to watch for changes to the aneurysm. They’ll also prescribe medication to lower your blood pressure and ease the stress on the weakened part of your aorta. Your provider will recommend surgery when its benefits outweigh its risks.

Survival depends on many factors, including the size of the aneurysm and whether it leads to complications. Large aneurysms can be dangerous. About 65% of people with a large, untreated aneurysm are still alive one year after diagnosis. Only 20% are still alive after five years.

Treatment can greatly improve your outlook and give you the chance to live a long, healthy life. That’s why it’s important to learn if you’re at risk for a thoracic aortic aneurysm and work with your provider to manage your condition.

There’s no specific way to prevent this condition. However, it’s possible to lower your risk for atherosclerosis (a leading cause of aortic aneurysms). Here are some steps you can take:

Your provider will tell you how to care for yourself if you have an aortic aneurysm. They may advise you to:

See your provider for a yearly checkup and go to all of your follow-up appointments. Call your provider sooner if you have:

Call 911 or your local emergency number if you have symptoms of an aneurysm rupture or aortic dissection. These are medical emergencies that require urgent care to improve your chance of survival.

If your provider diagnosed you with a thoracic aortic aneurysm, you may not know which questions to ask first. Here are a few to get you started:

This is an aneurysm that extends through part of your chest (thorax) and belly (abdomen). This type represents about 15% of all aneurysms that form in your aorta.

Learning you have an aneurysm in your chest can be frightening. Maybe you never thought about issues like your artery health or blood flow. Or, maybe you were born with a connective tissue disorder that made you highly aware of the inner workings of your body. No matter what you knew before, now is the time to learn more about your condition and how you can lower your risk for complications.

Talk to your healthcare provider about what you can expect in your situation. They’ll tailor treatment to your needs, answer your questions and give you the knowledge you need to move forward.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Vascular disease may affect your life in big and small ways. Cleveland Clinic’s specialists treat the many types of vascular disease so you can focus on living.