Patent foramen ovale is a leftover opening inside your heart from before you were born. After birth, it should close up on its own. But sometimes, it doesn’t. Depending on its size and placement, it might cause serious complications. Fortunately, the overall outlook for this condition is positive, even when serious enough to need treatment.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17326-patent-foramen-ovale)

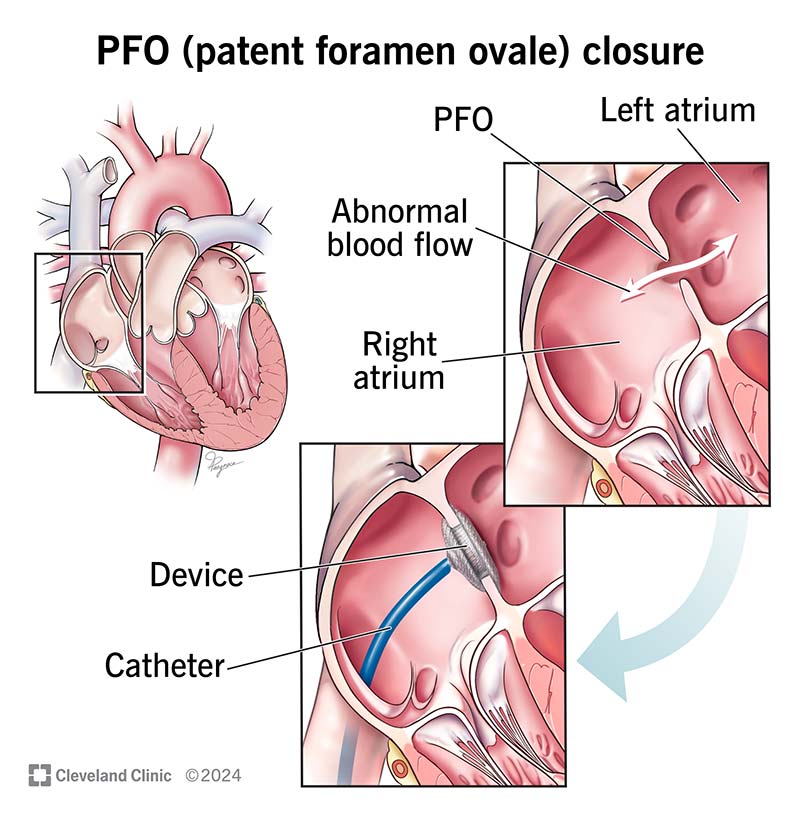

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is when you have a small flap or opening between the upper chambers (atria) of your heart. Everyone has this opening before birth. It’s called a foramen ovale. It usually closes before age 3. “Patent” means “open,” and “patent foramen ovale” means the foramen ovale is still open after your third birthday.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

PFO is somewhat common. Experts estimate that up to 1 in 4 adults have it. But most of the time, PFO doesn’t cause symptoms and won’t need treatment. But some uncommon problems related to having a PFO include stroke and transient ischemic attacks.

A fetus doesn’t use its lungs to get oxygen-rich blood. Instead, it comes from the placenta, delivered through the umbilical cord. Oxygen-rich blood from the umbilical cord enters the fetus’s heart and then uses the foramen ovale as a shortcut.

Taking that shortcut means blood skips the lungs (which aren’t doing anything yet). It goes straight from the heart’s right upper chamber (right atrium) to the left upper chamber (left atrium). From there, the blood eventually pumps out to the fetus’s brain (and everywhere else in its body).

The foramen ovale should naturally close when your baby starts breathing and blood goes to their lungs to get oxygen. The shortcut isn’t needed anymore, so it closes up.

Anyone can have patent foramen ovale. But people who need an echocardiogram for certain reasons are more likely to get a diagnosis. That usually affects:

Advertisement

A PFO is a small opening that lets blood leak between your heart’s upper chambers. It’s usually not a problem unless the leak is big enough. When it is, blood clots can slip through the opening. Those clots can either be from:

Clots that make it through a PFO can easily head straight to vital places like your brain. Once there, a clot can get stuck in tiny blood vessels and block blood flow, causing an ischemic stroke. Clots can also get stuck in other critical places, like inside the tiny blood vessels in your kidneys.

PFO usually doesn’t cause symptoms unless the opening is big enough for a lot of blood to pass through. That’s rare, but it can cause:

It’s much more common for healthcare providers to find a PFO when trying to find a reason why you had a:

Experts aren’t sure why PFO happens. But research shows it could be at least partly genetic.

Healthcare providers can diagnose PFO with a combination of methods. One easy way they might detect it is by just listening to your heart with a stethoscope (though this isn’t common). Your provider might be able to hear a murmur from the flow of blood through the PFO.

Echocardiograms are the main test to diagnose a PFO. There are two specific types of echocardiogram your provider might recommend:

Your provider may also suggest a bubble test with an echocardiogram or transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound. During a bubble test, they inject saltwater solution into your vein. The TCD ultrasound can detect the bubbles in your head if they pass through the PFO. An echocardiogram can show the bubbles as they pass through a PFO in your heart.

Advertisement

Most people with PFO won’t need treatment. But your provider may recommend treatment if you have a history or high risk of stroke or blood clots. Treatments can include:

The best treatment for you depends on several factors. Your healthcare provider is the best person to explain your options.

The treatments for PFO can sometimes cause complications, but this isn’t common. The complications vary by treatment. Some of the possible complications include:

Advertisement

Most people with PFO never know they have it because it doesn’t cause any issues. And while PFO can lead to serious, or even life-threatening, events, it’s also a very treatable condition. The outlook for adults and children who need a procedure to close a PFO is generally positive.

People under 25 who have a PFO closure procedure have the same life expectancy as people their age without a PFO. And in people under 40 with symptoms or a high risk of complications, closing a PFO can greatly improve survival chances and quality of life.

Most people with a PFO don’t even know they have one because it typically isn’t serious. But for some people, a PFO can lead to serious events like a stroke. If you have a PFO or a family history of them, talk to a healthcare provider. They can tell you more about your risks and offer advice on what to do about them.

PFO in newborns usually doesn’t need treatment unless it’s causing symptoms. Babies with a severe PFO may need surgery. But for most babies, a PFO will close up on its own before their third birthday.

Most PFOs don’t need treatment. It’s usually only necessary if the PFO creates a high risk for or has already caused a serious event.

Hearing that you have a hole in your heart can be scary. But for most people, it’s nothing to worry about — it’s just there and won’t ever affect your life.

Advertisement

But for some people, a patent foramen ovale (PFO) can be a real risk. If that’s the case for you, don’t hesitate to lean on your healthcare providers for support. They can tell you what to expect in your case and offer treatment recommendations.

The good news is that even in those who need treatment to close a PFO, the overall outlook is positive. Many people with treated PFOs go on to recover and live full lives.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic Children’s cardiology providers are experts in diagnosing and treating the congenital heart condition, patent foramen ovale (PFO).