Optic neuritis is when inflammation in your optic nerve causes pain, vision loss and other symptoms. This condition has strong links to chronic conditions like multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune diseases. Timely diagnosis and treatment may help optic neuritis and limit or delay more severe long-term effects or conditions.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/optic-neuritis)

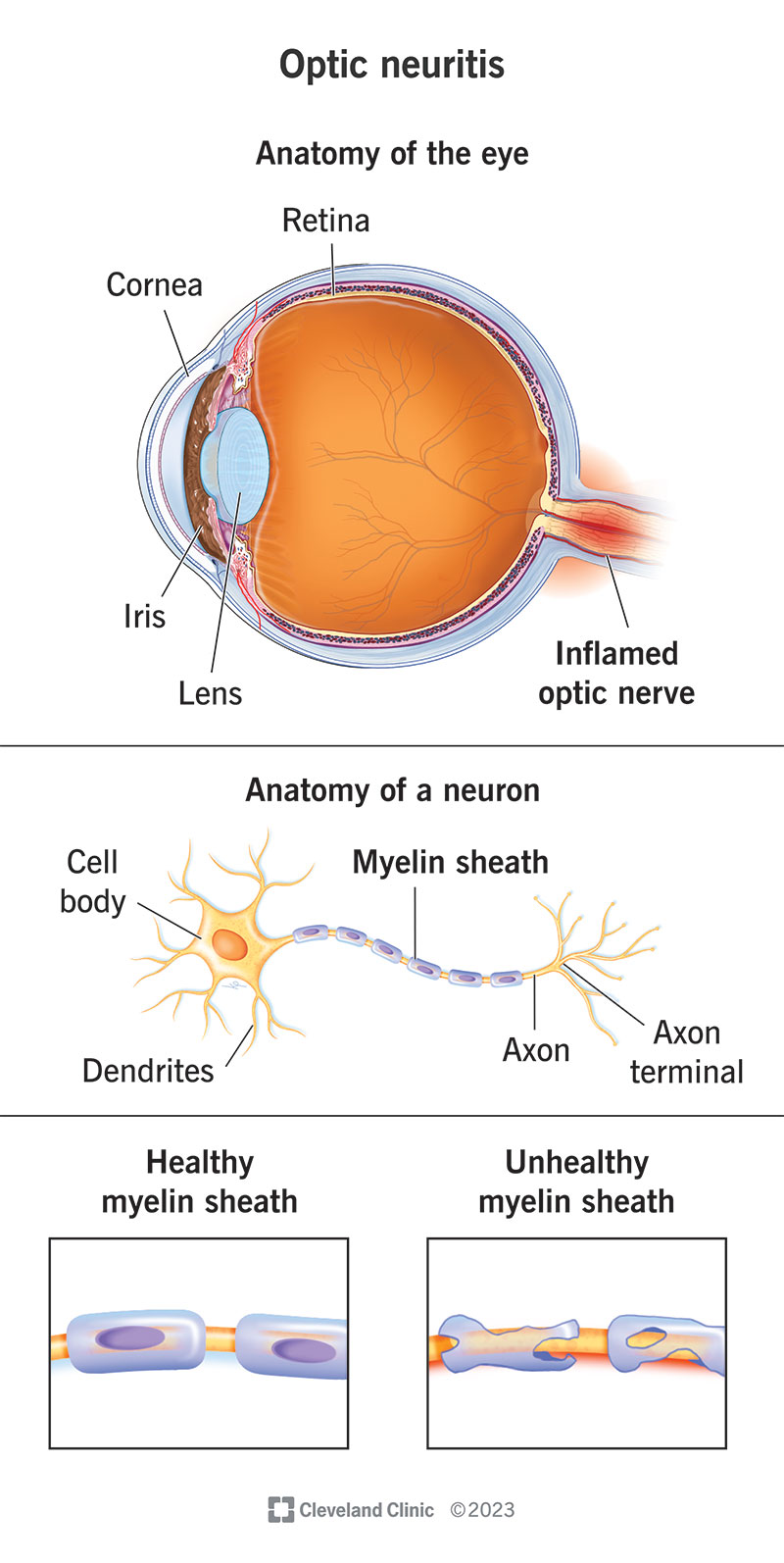

Optic neuritis (ON) is a type of neuropathy (nerve disease) that can cause eye pain and vision loss or vision changes. It happens when inflammation affects signals traveling through your optic nerve, which connects your eyes and brain.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The cells that make up your optic nerve have a fatty coating called a myelin sheath. When you have ON, that sheath deteriorates. The coating is protective. Without it, the nerve cells can’t send signals properly. That’s why various forms of vision loss are common symptoms of this condition.

There are three main types of optic neuritis:

Optic neuritis is common. In the U.S., there are about 5 new cases per 100,000 people each year.

Optic neuritis symptoms all revolve around your eyes and disruptions in vision. The changes usually stem from “retrobulbar” (meaning “behind the eyeball”) effects of optic neuritis.

Symptoms can include:

Advertisement

Optic neuritis happens when inflammation damages your optic nerve. There are several possible causes of that inflammation, including:

Optic neuritis can also have an unknown cause (idiopathic).

Researchers suspect that autoimmune and inflammatory conditions are a major cause or contributing factor to optic neuritis. They also suspect that the specific autoimmune conditions involved vary by the type of optic neuritis you have.

Your nerves are vulnerable to damage (neuropathy) from infections, and your optic nerve is no exception. Infections are often a triggering event that causes pediatric optic neuritis.

Four main types of pathogens can cause infections:

Viral infections are a common cause of optic neuritis, especially the pediatric form. Examples include:

Bacterial infections that cause optic neuritis usually pass to humans from animals or insects. Examples of bacteria or bacterial conditions include:

Fungal infections that can cause optic neuritis include:

Parasites that can cause optic neuritis often spread to humans from pets, especially cats and dogs. Examples include:

Prescribed medications and nonprescribed drugs can sometimes cause optic neuropathy (nerve damage). The most common types of drugs and toxins that can do this include:

Advertisement

Several other conditions can also cause or contribute to optic neuropathy. They include:

Certain factors make you more likely to develop optic neuritis. They include:

Advertisement

Vision loss is the main complication of optic neuritis. Your eye care specialist can tell you about any other complications that are possible or likely with your case.

Advertisement

An eye care specialist may suspect optic neuritis based on:

An eye exam is a key part of the process. The exam will include the following:

The following tests are also likely early on:

If the above checks and test results are consistent with optic neuritis, and another condition doesn’t better explain your symptoms, your eye care provider will probably refer you to a specialist. This may be a neurologist or a neuro-ophthalmologist (an eye care specialist who focuses on retinal and optic nerve issues and conditions).

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is a key part of diagnosing optic neuritis. The scan will involve contrast, a substance that makes tissue changes more visible on the scan. If you have optic neuritis, the affected optic nerve(s) will look brighter than a healthy optic nerve.

An MRI is important because it can detect brain lesions, which can be key indicators of MS. MRIs can also detect other lesions affecting your optic nerve and/or spinal cord, which are signs of NMO or MOGAD.

There are also several lab tests your provider might recommend. Lab testing is likely if:

Lab tests generally include blood and urine tests for signs of infection or autoimmune antibodies (especially antibodies that indicate you have NMO or MOGAD). A spinal tap (lumbar puncture) to test your cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) can also detect signs of infection or other changes in your cerebrospinal fluid.

The treatment for optic neuritis generally involves one or two key approaches:

Other factors could affect the treatments you receive. Your eye care specialist or other healthcare provider is the best person to tell you more about your options and the likely side effects, complications or other details you should know about.

What you can expect with optic neuritis varies depending on the type. Pain and vision loss are common, and these can affect one or both eyes.

Diagnosing optic neuritis can take a few different approaches, and it might feel frustrating while you go through the process. Know that you aren’t alone when this happens. Talking to your provider about your concerns lets them know you need reassurance or encouragement. And it’s always OK to let your eye care specialist or other healthcare providers know you need those kinds of support.

How long optic neuritis lasts depends on the type, the treatments you receive and how well those treatments work.

Typical optic neuritis is usually a short-term concern. The pain from it usually goes away within days (sometimes weeks), and treatment may speed that up. Most people get back clarity, sharpness and color vision over time, too. That can take as little as two weeks or as long as three months.

Atypical optic neuritis tends to be more severe, and the effects usually last longer, especially without treatment. Some people may go for six weeks or more without vision recovery, and it could be permanent, so getting this condition diagnosed and treated quickly is very important.

The outlook for optic neuritis varies, especially when it comes to the form you have:

Because of the connections between optic neuritis and other conditions, your eye care specialist may refer you to a neurologist, a rheumatologist or both. These specialists can often determine if you have any signs or symptoms of MS or similar conditions now, especially symptoms or signs you might not know to look for. Monitoring you for any changes can help catch those other conditions sooner, which is important because there are treatments that may slow the progress of those diseases.

Optic neuritis and nerve damage usually happen for unpredictable reasons. There are things you can do to lower your risk, but there’s no way to prevent all possible causes.

Steps you can take include:

You should see an eye care specialist if you suspect you have optic neuritis. They can begin the initial steps of diagnosing and treating this condition. They can also refer you to a neurologist, rheumatologist or other specialist who might also be able to help treat this condition. The sooner you get a diagnosis and treatment, the better the chances of a favorable outcome.

You should always see an eye care specialist if you notice vision loss. If you have sudden vision loss and don’t have a diagnosis for a condition that can cause it, you need emergency medical care right away. If you have a condition that can cause sudden vision loss (like migraines), your eye care specialist or another healthcare provider can tell you more about when it needs emergency medical care.

Once you have an optic neuritis diagnosis, your eye care specialist (and other healthcare providers, if you get a referral to them) will recommend regular follow-up visits. Those visits will help them monitor your condition and symptoms and adjust treatment if necessary.

No, not always. But the risk of developing multiple sclerosis is much higher if you have optic neuritis.

Here are some sources of information about optic neuritis:

Optic neuritis can be a painful and disruptive condition. Fortunately, large-scale research studies within the last few decades have made eye care specialists and other healthcare providers better prepared to treat the condition. If you have optic neuritis symptoms, you should see an eye care specialist quickly. The sooner you get a diagnosis and treatment, the better the odds of a favorable outcome.

If you have a chronic disease like multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder or MOG-antibody-associated disease connected to your optic neuritis, timely diagnosis and care can help with these also. There are treatments for these conditions that can slow their progress and that can help you in your daily life and routine, now and in the days ahead.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When a brain injury or another neurological condition affects your eyes, you’ll want the best care. Cleveland Clinic’s neuro-ophthalmology experts can help.