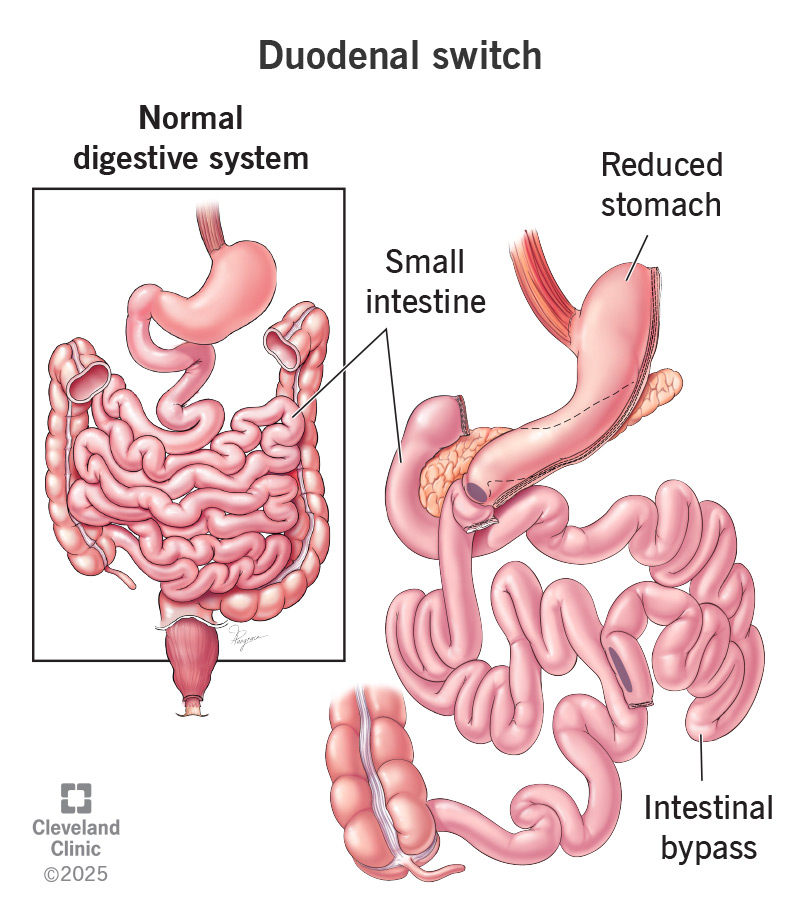

The duodenal switch is a weight-loss surgery designed to treat people who have severe obesity. It combines a sleeve gastrectomy with an intestinal bypass. The duodenal switch is more complex compared to other bariatric surgeries. But it’s also the most effective.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/22725-duodenal-switch.jpg)

Duodenal switch is a type of bariatric surgery that removes part of your stomach and shortens your small intestine. It decreases how much food you hold, digest and absorb. This change leads to significant weight loss. It’s one of the less common weight-loss procedures for obesity, but it usually leads to greater total weight loss.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

There are two types: The biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD/DS) is the traditional procedure, and the single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass with sleeve gastrectomy (SADI-S) is a newer modification.

The duodenal switch is a two-step surgery. First, your surgeon removes up to 80% of your stomach, making it much smaller and tube-shaped. This change prevents you from being able to eat too much food.

The second step is an intestinal bypass. Your surgeon shortens the length of your small intestine. They connect just the last section of your small intestine to your new stomach. When your food goes into your stomach, it bypasses most of your small intestine so that less of your food is digested. You can think of it as a shortcut in your digestion.

With duodenal switch, you end up eating less food, digesting that food quickly and absorbing fewer calories. This surgery also changes your metabolism and influences hormones that play a role in appetite and feeling full.

Duodenal switch is a procedure to treat Class III obesity. It’s not a weight loss surgery for everyone. Your healthcare provider carefully considers your health before deciding if this is the right weight-loss procedure for you.

Advertisement

Typically, duodenal switch is only for people who:

Examples of obesity-related health conditions are:

Duodenal switch surgery can help you lose weight and improve these or other obesity-related diseases.

If your healthcare provider believes you’re a good candidate for surgery, you’ll enter a screening process. This could involve:

Once you’ve met these benchmarks and scheduled your surgery, your healthcare provider will put you on a preoperative eating plan for a couple of weeks. This typically consists of eating meals that are low in fat and carbohydrates and high in protein.

Duodenal switch surgery is a laparoscopic surgery. The laparoscopic method is less invasive and uses small incisions instead of making a larger incision in your abdomen.

You receive general anesthesia so you’re asleep for the entire procedure.

There are two surgical methods to the duodenal switch: the traditional duodenal switch (biliopancreatic diversion) and the SADI-S.

The differences are in the second part of the surgery — the intestinal bypass. Both versions begin the bypass by dividing your small intestine near the top, in the section called the duodenum. Then, they bring a lower section of your small intestine up to attach to the top, bypassing the middle.

The surgery typically takes between two and four hours.

You’ll stay in the hospital for one to two days after surgery. It takes two to four weeks to make a full recovery. Your healthcare provider will give you instructions to follow during your recovery. This will include a list of what activities to avoid and what foods you can eat.

You’ll have frequent follow-up appointments with your healthcare provider in the first two years and periodic appointments for the rest of your life. The first two years will be your most dramatic weight-loss period. During this time, your provider will continuously monitor your progress and health.

Advertisement

Because there’s a risk of malnutrition, you’ll need to take nutritional supplements for the rest of your life. You’ll also need to give blood samples at regular intervals to make sure you’re getting enough nutrients.

Duodenal switch helps you lose weight and reduces your risk of serious obesity-related health problems. It can significantly improve your quality of life but requires that you make changes to your lifestyle.

Some more specific advantages are:

One of the main disadvantages of the surgery is that it relies on malabsorption, which can help you lose weight. But it also requires you to follow a specific eating plan and take specific supplements to get the nutrition you need. You need to follow the eating plan to avoid loose bowel movements, as well.

Other risks may include:

Duodenal switch surgery is one of the most successful bariatric surgeries. It results in a higher BMI loss (decreasing your BMI) when compared to gastric bypass. The surgery has a similar success rate for treating obesity-related health conditions like Type 2 diabetes.

Advertisement

You’ll likely spend a few days recovering in the hospital, then a few weeks recovering at home. During your recovery, your body will go through huge changes, including rapid weight loss. You may have some temporary symptoms during this time, including:

Ask your healthcare provider what you can expect during your recovery, including what activities you should avoid.

Duodenal switch surgery makes drastic changes to your digestive system. There are several aspects of your health that your provider will monitor. These include:

Advertisement

You’ll also have strict food guidelines to follow during recovery. This is to give your digestive system time to heal and adjust to the new changes. It may take one to two weeks to progress through each stage on your way back to eating how you used to. Your provider can go over the steps in more detail, but they follow this order:

Weight loss will vary from person to person, but there are some general trends. The most rapid weight loss happens in the first three months after surgery. During this time, you can expect to lose about 30% of your excess weight. Weight loss slows down a bit for the next three months after that. By the one-year mark, you may have lost 50% to 75% of your excess weight. Weight loss typically peaks between 12 and 18 months after surgery.

One isn’t better than the other. Both involve reducing the size of your stomach and changing the length of your small intestine The duodenal switch leans more on malabsorption, while gastric bypass leans more on eating less food. Your healthcare provider will recommend the best one for you based on your situation.

The duodenal switch is a two-part surgery that begins with a gastric sleeve. A gastric sleeve procedure reduces your stomach to about 75% of its original size. The duodenal switch goes a step further by having your food bypass most of the small intestine. This second part produces greater weight loss than the gastric sleeve alone, but also has more potential side effects.

Duodenal switch surgery is a serious intervention for a serious condition. It makes dramatic changes to the way your digestive system works, but it also has dramatic results. The most significant risk of the surgery is the risk of nutritional deficiencies. But if you’re prepared to keep up with your supplements and regular testing for life, you and your healthcare provider can make a plan to prevent this. The surgery can help you avoid the risks of obesity-related diseases and improve your quality of life.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have obesity and losing weight is an uphill battle, Cleveland Clinic experts can help you decide if bariatric surgery is an option.