Pericardiocentesis is a procedure to take extra fluid out of your pericardium, a protective pouch that surrounds your heart. A provider uses a needle and imaging to get to the problem area. This procedure could save your life if you have so much fluid in your pericardium that your heart doesn’t have enough room to beat.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22613-pericardiocentesis)

Pericardiocentesis (pronounced “pair-ick-arr-dee-oh-sen-TEE-sis”) is a procedure that drains extra fluid from around your heart. It’s often a treatment for a life-threatening condition that can stop your heart.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

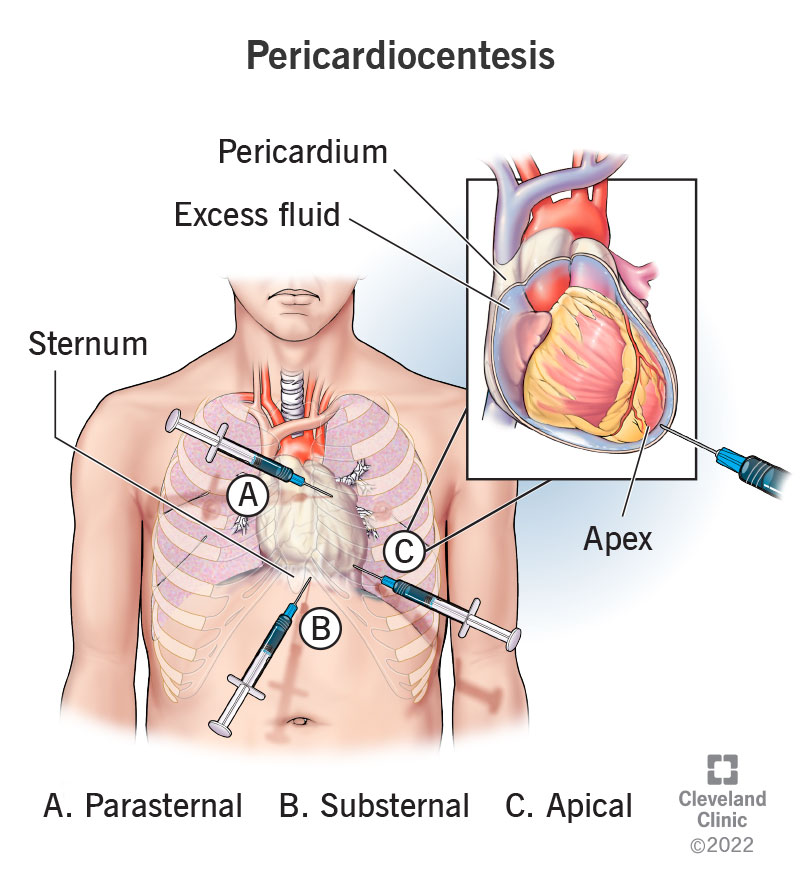

This procedure involves inserting a needle into your chest until the tip of the needle is inside your pericardium (the pouch that surrounds your heart). Once there, providers can use the needle to drain fluid directly or place a drain that can remove fluid slowly over time.

A pericardiocentesis procedure treats pericardial effusion, or too much fluid in your pericardium. (A small amount of fluid is normal.) Your pericardium holds your heart in place and cushions it from outside movement.

Pericardial effusions can lead to cardiac tamponade. This is a medical emergency because it can make your heart stop, which can be deadly within minutes to hours.

A provider can use pericardiocentesis as an emergency or non-emergency treatment. In emergencies, pericardiocentesis treats either cardiac tamponade or severe pericardial effusions that will cause cardiac tamponade. In non-emergencies, providers often use it as a diagnostic test to determine what’s causing extra fluid to build up.

People with too much fluid in their pericardium may need a pericardiocentesis. Common causes of this include:

Advertisement

Pericardiocentesis is a relatively common procedure. Providers in the United States perform more than 29,000 of these procedures each year.

After a provider diagnoses you with either a pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade, they'll determine how severe your condition is and the best way to treat it.

On the day of the procedure, you'll need to fast (not eat) starting eight hours before the procedure (you can have clear liquids up to two hours before the procedure starts).

How a provider prepares for a pericardiocentesis procedure depends on whether or not it’s an emergency. With a slow-growing effusion (a non-emergency), your healthcare provider can schedule the procedure. In most cases, except in the most extreme emergencies, you’ll receive local anesthesia right before the procedure.

Your provider will:

Pericardiocentesis is a procedure that involves several healthcare providers from different backgrounds. It will likely involve one or more doctors, nurses, imaging technicians and more.

Imaging guidance

Before inserting the needle, the healthcare provider performing this procedure will work with an imaging technician to find the safest, simplest way to reach your pericardium. The most common type of imaging is ultrasound (echocardiogram), which is safe and easy to perform at the time of the procedure. Fluoroscopy is another imaging option.

Imaging is important because it helps the provider insert the needle right where it needs to go.

A provider can do this procedure without imaging help in extreme emergencies. However, this is extremely rare and has a higher risk of complications. It’s usually not an option unless there’s no other choice.

Needle placement

Unless you’re in immediate danger of your heart stopping, your provider will use a local anesthetic to numb the area just before they insert the needle. They may also use a scalpel to make a small cut on your skin to make it easier to insert the needle.

Depending on where the fluid is in your pericardium, there are several places to insert the needle. The most common location is under your sternum, also known as your breastbone. This substernal approach usually gives easy, direct access to your pericardium.

Advertisement

Less common entry points are:

Once they insert the needle, they’ll angle it so it enters your pericardium, but not your heart. Once the tip of the needle is in your pericardium, the provider can start drawing out the extra fluid inside.

Depending on how much fluid is inside your pericardium, it may take only minutes to remove enough fluid. It takes about 10 to 20 minutes to perform a pericardiocentesis procedure. If there’s a lot of fluid, they may insert a catheter tube to drain fluid out more slowly.

Once they’ve drawn out enough fluid, your provider can pull the needle (or catheter) out, or they can leave a drainage catheter in place for a day or two to remove more fluid. When removing the needle or drain, they’ll finish the procedure by bandaging the spot.

After the procedure, your healthcare provider may:

Advertisement

Besides being a life-saving procedure when your heart is under pressure from fluid around it, a pericardiocentesis:

Studies have found success rates higher than 90% (with some as high as 100%) for a pericardiocentesis procedure.

Depending on the cause and treatment options, fluid can continue to build up after the initial drainage. If this happens, your provider might recommend you see a surgeon to discuss a more permanent procedure called a pericardial window.

Pericardiocentesis complications happen in about 5% to 40% of cases. The risk of complications is lowest when imaging like an echocardiogram or fluoroscopy helps the provider “see” where to direct the needle.

In extreme emergencies, it’s possible to do this procedure without imaging help. But this is very rare and should only happen when there’s no other option.

Advertisement

Even with imaging, a pericardiocentesis procedure involves inserting a needle very close to several of your vital organs and major blood vessels. That means there’s a risk of injuring any of the following:

Any kind of medical procedure that needs to pass through your skin also creates the risk of infection. When these infections spread, it can lead to an overwhelming reaction from your immune system. That overreaction, known as sepsis, is a life-threatening medical emergency.

Most people will start to feel better quickly when a provider drains the fluid or immediately afterward. You’ll need to rest for 12 to 24 hours afterward while providers keep an eye on your condition. The overall pericardiocentesis recovery time depends on:

Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what to expect when it comes to your recovery and when you can resume your normal activities.

Your healthcare provider will schedule follow-up visits to ensure you don’t have any complications or additional need for treatment. Some people will need more than one procedure because pericardial effusions can happen more than once. This is especially the case for certain cancers, infections, like tuberculosis, or other conditions.

Several symptoms or other indications mean you need medical attention if you’ve recently had this procedure.

Symptoms of cardiac tamponade

The symptoms of cardiac tamponade include:

Symptoms of infection and sepsis

You should also go to the hospital immediately if you have any infection symptoms. These can be a sign of sepsis, a life-threatening condition that’s as serious as a heart attack or stroke. The symptoms of sepsis include:

It may sting when a provider injects a local anesthetic into your skin. But the anesthetic will keep you from feeling pain in that area. Instead, you may feel pressure when a needle goes into your pericardial sac.

Yes, they are different names for the same procedure.

It may be scary to see a needle coming at you and going toward your heart. But pericardiocentesis is a proven way to relieve the pressure and symptoms of severe pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. Thanks to advances in treatment techniques, technology and healthcare provider training, this procedure usually has good outcomes. While it does have some risks, the potential for this procedure to save lives almost always outweighs any risks. Ask your provider if you have questions you’d like them to clarify about the procedure.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Whether your pericardial disease comes on acutely without warning or is chronic, Cleveland Clinic has the best treatments for this heart condition.