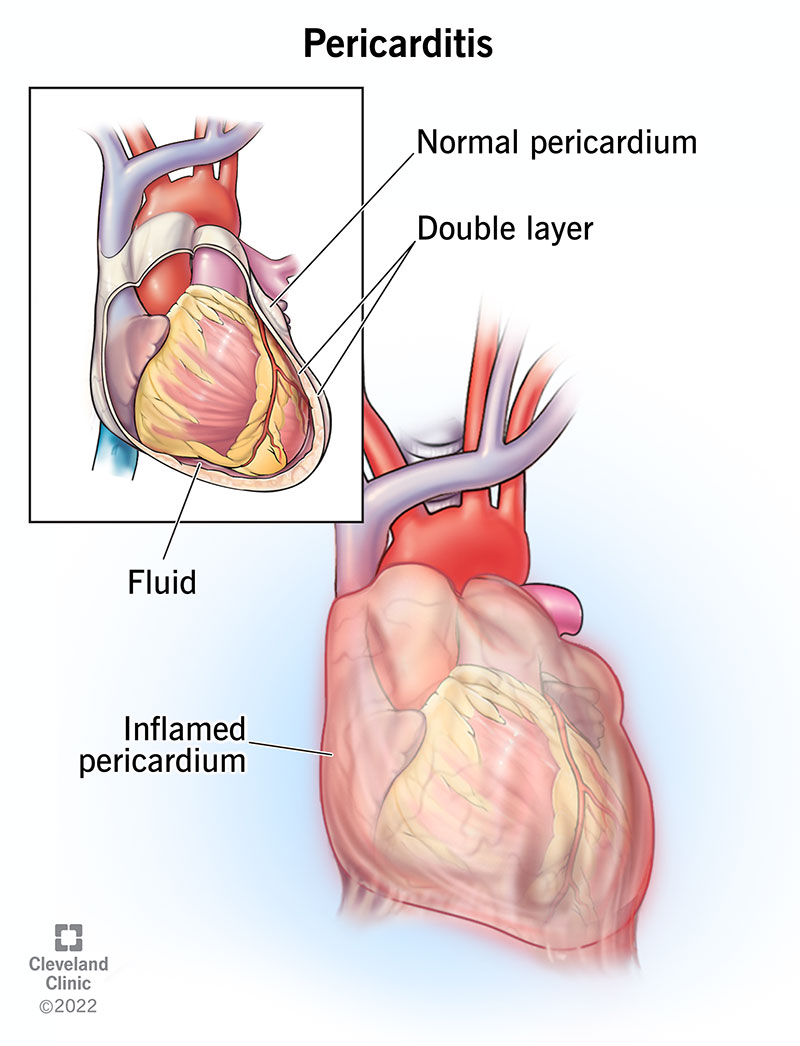

Pericarditis is an inflammation of the sac that contains your heart. Sharp chest pain that feels better when you lean forward is the main symptom. Pericarditis has many possible causes, ranging from infections to injuries to your chest. But in many cases, healthcare providers can’t find the cause. Prompt treatment is key.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/17353-pericarditis)

Pericarditis is inflammation of the thin sac around your heart, called the pericardium. It usually comes on quickly and can last weeks to months. The main symptom is sharp chest pain.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Pericarditis can affect anyone. But it’s most common in males between the ages of 16 and 65. An estimated 28 people per 100,000 get this condition each year. It’s often treatable.

There are several types of pericarditis based on the duration and cause of it.

Types based on the duration or timing include:

Types based on the cause include:

Constrictive pericarditis can be a complication of several types of pericarditis. It happens when the layers of the sac stiffen, scar and stick together. This is a severe form.

Advertisement

Chest pain is a common symptom of pericarditis. The pain is sharp and stabbing. It often gets worse when you cough, swallow, breathe deeply or lie flat. It can ease when you sit up and lean forward. These specific signs often point to pericarditis, not a heart attack. The pain may also spread to your back, neck or left shoulder.

Other pericarditis symptoms include:

If you have any of these symptoms, call a doctor right away. If you feel your symptoms are a medical emergency, call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room.

Pericarditis has several possible causes. In North America and Western Europe, the most common causes of acute pericarditis are unknown (idiopathic) or viral.

Healthcare providers group causes into two types: infectious and non-infectious.

Infectious causes include:

Examples of non-infectious causes include:

Your risk of pericarditis is higher after:

Too much fluid buildup in your pericardium can cause a complication called pericardial effusion. If the fluid builds up quickly, it can cause cardiac tamponade. This is a severe compression of your heart that keeps it from working as it should. It’s a medical emergency.

This is why it’s important to see a healthcare provider as soon as possible if you have symptoms of pericarditis. Getting treatment early can help prevent these complications.

A healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms and medical history (like if you’ve recently been sick). They’ll review your history of other conditions and surgery to look for risk factors.

Your provider will listen to your heart. Inflamed tissue makes a rubbing or creaking sound, called the “pericardial rub.” They may also hear crackles in your lungs if fluid has built up.

Your provider may suggest other tests to confirm a pericarditis diagnosis. These tests can also check for complications and may help find the cause. Tests may include:

Advertisement

Treatment for pericarditis most often involves medication and limiting physical activity. If it’s severe, you may need fluid drainage and/or surgery.

Most people with acute pericarditis only need medicine, like:

Advertisement

You may need other medications depending on the underlying cause of pericarditis.

If you have chronic or recurrent pericarditis, you may need to take NSAIDs or colchicine for several years, even if you feel well.

It’s important to rest while you’re recovering from pericarditis. Physical activity can make the inflammation worse. Your healthcare provider will let you know how much and how long you need to limit physical activity.

Gradually getting back to moving is also crucial to help prevent pericarditis from coming back again.

If fluid builds up in your pericardium and compresses your heart, you may need a procedure called pericardiocentesis. Your provider uses a long, thin tube to drain the extra fluid.

If your provider can’t drain the fluid with a needle, they’ll do a procedure called a pericardial window. They’ll make an opening in your pericardium through a small chest incision to drain the fluid.

If you have constrictive pericarditis, you may need to have some of your pericardium removed. This surgery is called a pericardiectomy.

Surgery isn’t usually a treatment if you have pericarditis that keeps coming back. This is because inflammation makes healing after surgery difficult. But your provider may talk to you about it if other treatments don’t work.

Advertisement

You’ll need to see your healthcare provider regularly after the initial diagnosis. They’ll want to check in on your symptoms and heart health. And they may need to adjust your treatment.

See a provider immediately if you have swelling in your feet, legs and ankles or shortness of breath every time you exert yourself. These may be signs of constrictive pericarditis. It can be life-threatening.

You’ll need to take it easy while recovering from pericarditis. After you recover, you should be able to return to your normal activities. Don’t return to intense exercise until your provider says it’s OK. Your provider will talk to you about what to expect based on your unique situation.

With treatment, the outlook for acute pericarditis is very good. Most people recover fully. Mild cases may get better with rest. Without treatment, you may end up with chronic pericarditis.

If bacteria or tuberculosis is the cause, you may have up to a 30% risk of constrictive pericarditis. Cardiac tamponade, a complication, is more likely to happen when cancer or infection causes the condition.

About 15% to 30% of people with pericarditis have episodes of pericarditis that come and go for many years.

If you get prompt treatment for pericarditis, you’ll most likely make a full recovery. Continuing with your treatment can help prevent it from happening again. That’s why it’s important to keep taking prescribed medicines and go to all of your follow-up appointments. Get familiar with the symptoms of this condition so you can get quick treatment if it comes back.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Whether your pericardial disease comes on acutely without warning or is chronic, Cleveland Clinic has the best treatments for this heart condition.