Cachexia (wasting syndrome) is a condition that causes significant weight loss and muscle loss. It often affects people with severe chronic diseases like advanced cancer and heart disease. A cachexia diagnosis often means that the end of life is near. Healthcare providers treat cachexia by managing the underlying condition and by improving nutrition.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/cachexia-wasting-syndrome)

Cachexia (wasting syndrome) is a serious complication of severe chronic diseases like cancer, Alzheimer’s, dementia, obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure. It’s a common condition estimated to affect about 9 million people worldwide.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The name “cachexia” (kuh-KEK-see-uh) is a combination of the Greek words for “kakos” and “hexis”. These names roughly translate into the terms “bad body” or “poor physical state”. They reflect how cachexia may affect your appearance and your overall well-being.

In cachexia, your body changes dramatically as you lose weight and muscle and become increasingly weak. It affects your quality of life and can be life-threatening. Right now, the only treatment for cachexia involves managing the underlying condition and taking steps to improve nutrition. Researchers are investigating medications that may keep cachexia symptoms from getting worse.

Healthcare providers may use the term “cachectic” when talking about cachexia symptoms. Symptoms include:

Advertisement

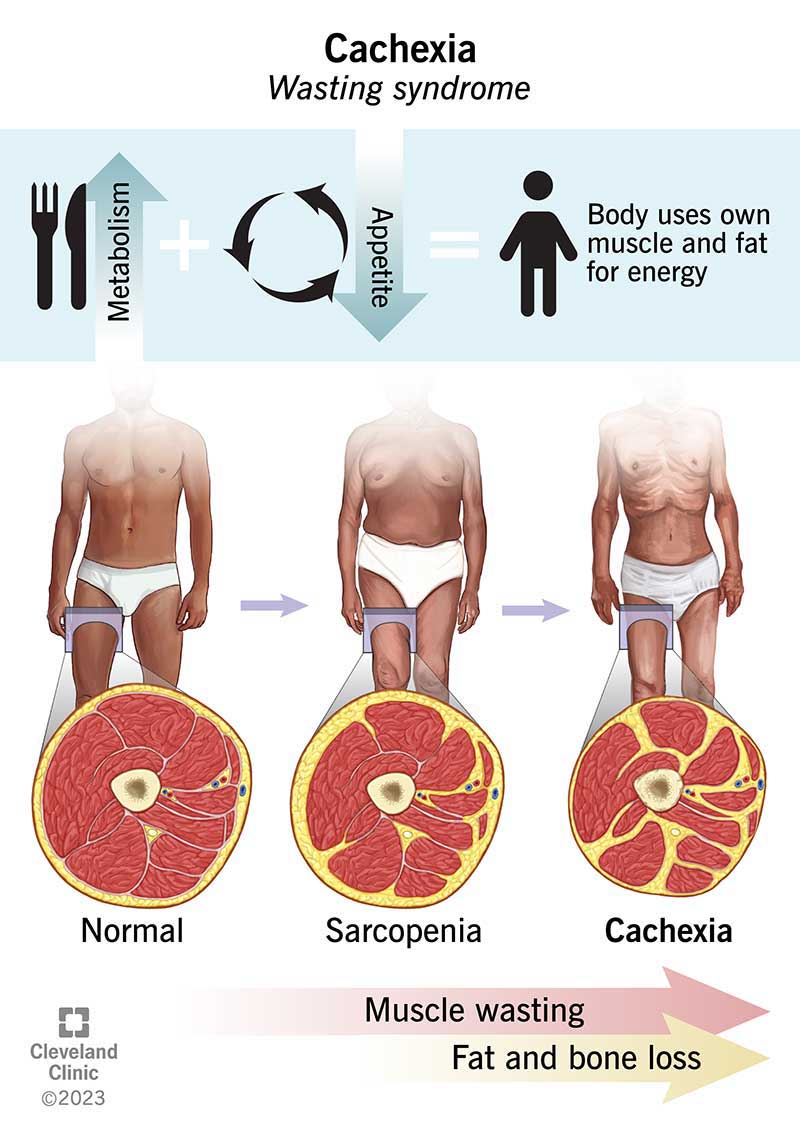

In general, cachexia happens when there’s a disconnect between energy demand (your metabolism) and energy supply (food). The disconnect often happens because you’re very sick with a chronic medical condition like cancer or heart disease.

When you’re very sick, your metabolism speeds up as your immune system reacts to the disease, creating an ongoing demand for more energy from the food you eat. But the same condition that sparks your metabolism may affect your appetite.

Without an adequate energy supply from food, your body taps your muscles and fat to get more energy, so you lose muscle mass and weight.

The specific causes of cachexia include:

Cachexia most often happens if you have cancer. Research shows 40% of people with cancer have the condition when they’re first diagnosed with cancer, and 70% of people with advanced or late-stage cancer have cachexia.

But people with other advanced chronic diseases may develop cachexia, such as:

Cachexia can be life-threatening. For example, this condition accounts for 20% of all cancer-related deaths. The muscle loss it causes can affect your heart and your ability to breathe.

In general, a cachexia diagnosis often means the end of life is near. That’s understandably hard news for someone with the condition and for the people who love them. A cachexia diagnosis often causes mental health concerns like anxiety and depression.

Advertisement

Weight loss from cachexia changes your appearance, which may make you feel self-conscious. It makes you weak and affects your ability to take care of yourself.

Research shows cachexia may create tension between those with the condition and the people who care for them. If someone you love has cachexia, you may feel as if you’re watching them waste away as they lose weight, muscle and their independence.

In some cases, caregivers see encouraging people to eat as a way to slow the end-of-life process. They become frustrated and upset when their loved one refuses to eat. Tension about eating can make social interactions upsetting. For example, people who are near the end of life may pretend to be asleep during visits with family and friends so that their visitors don’t try to make them eat.

Healthcare providers will do a physical examination. They’ll ask about your overall health and medical history, specifically if you’re receiving treatment for one of the chronic diseases that leads to cachexia. They may do tests to evaluate your overall fitness and muscle strength. They may order blood tests, including a comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP), and a computed tomography (CT) scan.

Advertisement

Healthcare providers focus on treating the underlying conditions. They may also recommend ways to increase how much you eat when you feel like eating.

For example, providers may recommend that you have frequent small meals using food that’s high in protein, fat and calories. Frequent small meals make a difference because you get more calories when you eat small amounts of food. Ask your nutritionist to recommend food choices for cachexia that help you get the most benefit out of every bite you take.

Not at the moment. While research shows the drug megestrol acetate may improve your appetite so you eat more and gain weight, the drug doesn’t have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for cancer cachexia treatment. In some situations, your provider may prescribe corticosteroids that you’ll take for a short period of time.

If you’re caring for someone with cachexia, it’s important to remember that cachexia in advanced disease increases metabolism so people aren’t hungry. That’s why increasing calories doesn’t always ease cachexia. And forcing someone to eat may be counterproductive because it can worsen symptoms like nausea and vomiting.

Instead of encouraging your loved one to eat more, consider other ways you can support them, like offering to give them a massage or apply lotion or lip moisturizer.

Advertisement

If you have this condition, you’ve been living with a serious, terminal illness. Depending on your situation, a cachexia diagnosis may mean the end of life is near. But many different diseases lead to cachexia and your situation may be completely different from another person’s. If you’re receiving treatment for cachexia, your healthcare team is your best resource for information about what you can expect.

There’s no set guidance on living with cachexia, but these suggestions may be helpful:

Healthcare providers typically don’t recommend tube feeding (enteral feeding) and parenteral nutrition because these treatments don’t improve cachexia or help you to live longer.

Tube feeding delivers liquid nutrition through a flexible tube that goes into your nose or directly into your belly or small intestine. Parenteral nutrition is nutrition that you receive intravenously through an IV line.

Cachexia (wasting syndrome) affects people with severe chronic diseases, including advanced cancer and heart failure. Often, it represents one of the final steps in the journey from life to death. That’s hard news to hear, whether you have cachexia or care for someone who does. Your providers understand the many ways that cachexia disrupts daily life and your emotional equilibrium. If this is your situation, don’t hesitate to ask your healthcare team about mental health support.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Living with a serious illness can be challenging. Cleveland Clinic palliative care providers are here to offer you physical, social and emotional support.