Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia is a type of arrhythmia (irregular heart rhythm). It happens when your heart’s electrical system malfunctions, making your heart’s ventricles beat too quickly. In some cases, this condition is dangerous because it can cause your heart to stop suddenly. It’s usually treatable with quick medical care.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/23215-monomorphic-ventricular-tachycardia)

Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia is a type of irregular heart rhythm (arrhythmia) that happens when the lower chambers of your heart beat at a dangerously fast pace. It can turn into a dangerous — or even deadly — problem depending on how and when it happens.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Ventricular tachycardia can easily turn into ventricular fibrillation, which is a deadly arrhythmia that can stop your heart. If you’re with someone who passes out and has no pulse, it’s important to call 911, start CPR immediately and find a nearby automated external defibrillator (AED).

If you don’t know how to give CPR, 911 operators often have training in how to direct you over the phone on how to give CPR. If you’re in a public place, many buildings and facilities also have on-site automated external defibrillators (AEDs), which can be a critical, life-saving tool in these situations.

The name “monomorphic ventricular tachycardia” breaks down into the following terms and meanings:

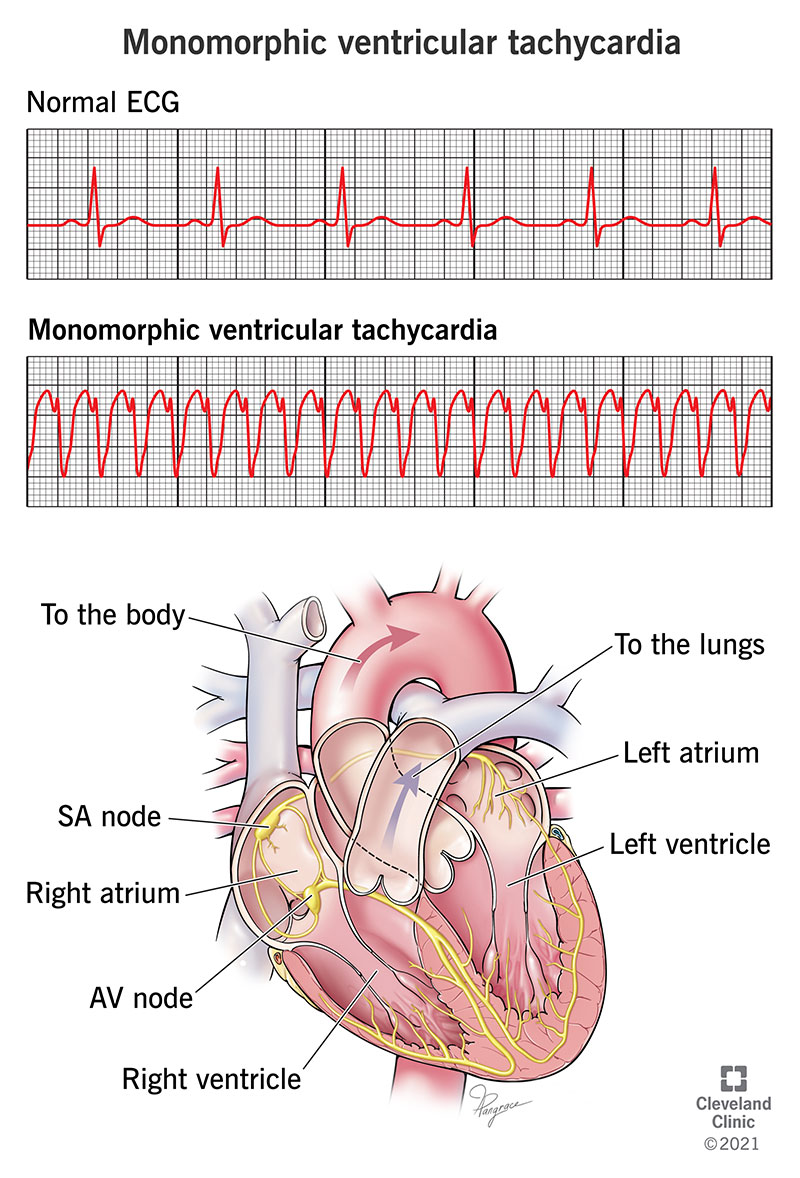

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) means that your lower chambers beat fast yet insufficiently. This is usually due to abnormal electrical circuits in the ventricular muscles. The term "monomorphic" comes from how this heart rhythm appears on an electrocardiogram (often shortened using one of two abbreviations, ECG or EKG). Monomorphic VT makes up about 70% of all cases of VT.

Advertisement

An EKG detects your heart’s electrical activity using several sensors (usually 12) called electrodes that attach to the skin of your chest. Those electrodes pick up the electrical activity and show it as a series of waves on either a paper printout or a screen display. Monomorphic VT means that the waves all consistently have the same shape.

Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia is similar to monomorphic VT but with a key difference. Polymorphic means “many shapes.” On an EKG, polymorphic VT waves change from beat to beat. That means the electrical activity in your heart is much more unstable than with monomorphic VT.

Ventricular tachycardia is more common in men. It tends to affect adults, especially older adults or those with any form of heart disease, especially heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. It can happen to children, but this is rare and it tends to only happen with structural heart diseases (conditions where part of their heart has the wrong shape or placement) that they had when they were born (congenital). You can also inherit conditions that commonly cause ventricular tachycardia, such as Brugada syndrome or arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy.

Ventricular tachycardia and a related arrhythmia, ventricular fibrillation, are responsible for about 300,000 deaths in the U.S. each year.

Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia usually happens because of a malfunction in your heart’s electrical system. That malfunction makes the ventricles beat so fast that they don't have enough time to fill up with blood before they have to squeeze again. It can also cause the ventricles to squeeze at the wrong time, throwing them out of sync with the upper chambers of your heart.

Ventricular tachycardia can also worsen into ventricular fibrillation. This is the same effect where your heart's lower chambers can't fill up with blood, but it's more severe. With ventricular fibrillation (often shortened to v-fib), the ventricles don’t squeeze correctly at all and instead just twitch or quiver.

Because your heart isn’t pumping effectively, ventricular fibrillation can easily cause cardiogenic shock or sudden cardiac arrest, which is when your heart can’t pump enough blood to support your body. Ventricular tachycardia can also skip v-fib entirely and go straight to cardiac arrest. Sudden cardiac arrest is deadly in minutes without immediate CPR (and it's often called sudden cardiac death when attempts to revive the affected person are unsuccessful).

Advertisement

Some people with monomorphic VT might not have any symptoms at all. When there aren’t any symptoms, VT is usually short-lived and not severe.

The symptoms of monomorphic VT include:

Monomorphic VT can happen for a number of reasons. These include:

Advertisement

Advertisement

Monomorphic VT isn’t contagious, so you can’t pass it from person to person. However, some conditions that cause it are genetic, meaning children can inherit them from one or both parents. It can also happen because of inflammation from infections, and those infections are sometimes contagious.

Diagnosing monomorphic VT requires an in-hospital electrocardiogram. A doctor can diagnose this condition using this test based on the wave pattern they see on your EKG. An EKG is the only way to diagnose monomorphic VT because EKG is the only way to see the consistent wave pattern in your heart's electrical activity.

When you have non-sustained monomorphic VT, it may take tests that use the same principle as an EKG but don't require you to be in a hospital. These include ambulatory monitors, which are devices that record EKG readings over a longer period. You can wear these home and, depending on the type of monitor, you can wear them for days or even weeks.

If you don’t have sustained ventricular tachycardia and don’t have any symptoms, you probably won’t need treatment for ventricular tachycardia. However, your healthcare provider will probably caution you to watch for any symptoms that mean this condition is becoming a problem for you.

Because sustained ventricular tachycardia can lead to cardiac arrest (either directly or after turning into v-fib), it’s important to return your heart to a normal rhythm. That often requires one or more different approaches, ranging from medication to surgery.

Depending on why it happens, monomorphic VT is usually treatable but isn't always curable. The underlying cause is what's most likely to determine if your case is curable.

Treatment for monomorphic VT usually involves one or more of the following:

The potential complications and side effects that you might have from any of the above treatments can vary greatly. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what’s most likely to happen in your case. That’s because they can take into account the specific treatments you need (or already received), as well as your health history and specific circumstances.

Because monomorphic VT requires an EKG to diagnose, you can’t know you have it without getting medical attention. That also means you can’t care for it yourself without first seeing a healthcare provider.

Most people will start to feel better when receiving treatment, especially if that treatment slows down their heart rate and restores their heart to a normal rhythm. In other cases, you might need additional care or even surgery before you start to feel better. If you need surgery, you might not feel fully recovered until you also recover from the procedure. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what your likely recovery time is and what — if anything — you can do to help you have a faster or smoother recovery.

If you don’t have symptoms from monomorphic VT, you probably won’t need medical treatment.

If you do have symptoms of monomorphic VT, you need immediate emergency medical care. That’s because ventricular tachycardia can easily lead to cardiac arrest (either directly or by turning into v-fib first).

This condition may be very short, lasting only for a few moments at a time, or it can last for several minutes. However, this condition is dangerous, which means you shouldn't let it continue for too long. That's why emergency medical care is so vital to avoid complications or death.

Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, especially without symptoms, is usually not a harmful problem.

When you have sustained monomorphic VT, especially with symptoms, you need emergency medical attention. Without that care, your heart could develop an even worse arrhythmia or stop altogether.

In most cases, monomorphic VT is an unpredictable problem. That means it’s not possible to prevent it. The only way to prevent it is to avoid circumstances or activities that might make it possible for you to develop it. An example of this is avoiding recreational drugs like methamphetamine or cocaine.

If monomorphic VT happens because of another condition you develop, you might be able to reduce your risk of VT by avoiding or delaying that condition. However, this isn’t always possible. Monomorphic VT is also not preventable when it happens because of an inherited condition or a condition you have at birth.

Your healthcare provider is the best person to guide you on what you can do to take care of yourself once you have a diagnosis of monomorphic VT. In general, you should do the following:

You should see your healthcare provider regularly as recommended. You should also see them if you start to develop symptoms or if your symptoms change and start to interfere with your life. You should also ask your provider about the symptoms or warning signs that mean you need to call their office or seek medical care.

You should go to the hospital ER if you have any of the symptoms of monomorphic VT. That’s because the symptoms of this condition are very similar to symptoms seen with other dangerous conditions like heart attack or pulmonary embolism.

The symptoms to watch for include:

Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia is a condition that can be dangerous. If you have the symptoms of this condition, it’s important to get medical attention quickly. The sooner you get care, the more likely healthcare providers can diagnose and treat your problem before it turns into something worse. While this condition isn’t always curable, it’s usually possible to treat it in ways that allow you to return to your life and the activities you most enjoy.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your heart rhythm is out of sync, the experts at Cleveland Clinic can find out why. We offer personalized care for all types of arrhythmias.