Calciphylaxis is a rare, painful disease that happens when calcium deposits form in your blood vessels and block blood flow to areas of your skin. This can lead to open wounds that are prone to dangerous (or even deadly) infections. People with moderate to severe kidney problems get this condition more often than those without kidney issues.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/calciphylaxis-illustration)

Calciphylaxis (pronounced “kal-si-fuh-lack-sis”) is a rare, painful and often fatal disease that causes calcium deposits to form in your blood vessels and block blood flow. This leads to areas where skin and tissue just underneath break down and die.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

In most cases, calcium deposits form in blood vessels that supply your skin and the tissue just underneath it. In rare cases, deposits can form in your eyes, lungs, brain, muscles and intestines.

When it affects surface tissue like skin, calciphylaxis is extremely painful. It also causes the affected area to become an open wound. The skin and tissue around that wound die, and the damage from the dead tissue spreads. These wounds are slow to heal and can lead to major complications.

Infection in a wound can spread through your body and cause an overreaction of your immune system called sepsis. This condition is the most dangerous complication of calciphylaxis.

In the U.S., calciphylaxis happens to about 35 of every 10,000 people who are on dialysis.

This condition is more common in females. They’re twice as likely to develop the condition as males. The average age at diagnosis is 50 to 70.

Calciphylaxis has two types based on when they happen:

Advertisement

Calciphylaxis symptoms may include:

Your experience of calciphylaxis changes with time. Researchers have found differences between early-stage and late-stage symptoms.

Early stage

Pain starts out changing between mild and severe. The feeling of pain may start before lesions or any other visible signs appear.

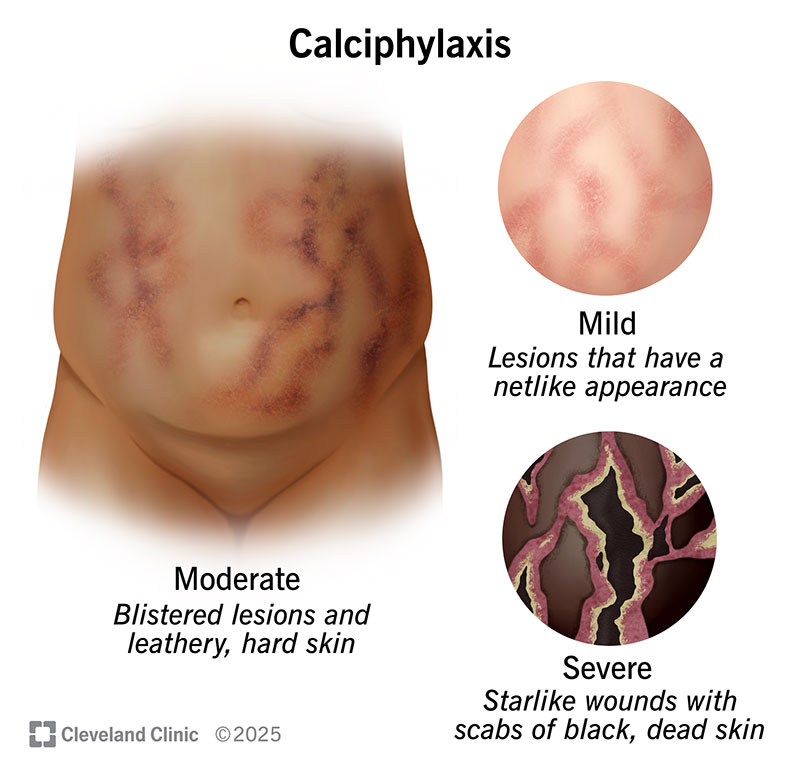

Areas of skin turn red, purple, brown or black. These lesions are on your belly and thighs or on your fingers and toes. Lesions usually have a netlike look. They may also blister, and the affected area of skin may become hardened and leathery. When calciphylaxis is due to cancer, lesions are typically firm, whitish nodules.

Late stage

Pain remains severe. The affected areas can also become very sensitive to pressure or touch. This makes the pain more intense.

Lesions usually become wounds that spread outward in starlike shapes. The wounds often have a foul smell. Areas of dead skin and flesh may turn black, look like scabs and fall off.

The exact cause of calciphylaxis is unknown. But research suggests it takes more than one factor to cause it. These factors, which include imbalances of certain substances, can team up to cause this condition.

These factors include:

Several conditions and risk factors may be linked to calciphylaxis, including:

Advertisement

How to lower your risk

Having longer or more frequent dialysis sessions may help remove calcium and other substances. But you can also adjust what you eat so you take in less calcium or phosphate. Your healthcare provider may ask you to switch from warfarin to a different blood thinner. They’ll choose one that doesn’t affect your body’s use of vitamin K.

Complications of calciphylaxis may include:

A healthcare provider may suspect calciphylaxis based on your condition, symptoms and a physical exam. This exam includes looking and feeling for any changes to your skin or the area just under it. They’ll also ask questions about your medical history as they try to make a calciphylaxis diagnosis. Once a provider suspects the condition, they’ll order medical tests to learn more.

A healthcare provider may order the following tests:

Advertisement

Researchers don’t fully understand calciphylaxis. So, there aren’t many clear-cut guidelines on the best calciphylaxis treatment. Currently, the disease isn’t curable. But your symptoms can go away if treatment is successful. Treatments include wound care and pain management, nutrition and medications.

In general, healthcare providers will focus on:

Advertisement

Talk to your healthcare provider if:

Your provider is the best source of information on your risk factors, what symptoms you should watch for and when you should seek medical attention. They can catch calciphylaxis early, which can be helpful in your treatment.

If you have calciphylaxis, your healthcare provider can guide you on when to call their office or seek immediate medical care for lesions or wounds. Among the biggest things to watch for are signs of infection or problems in and around a wound. These include:

Questions to consider asking your healthcare provider may include:

The outlook for calciphylaxis tends to be poor because of a lack of understanding of the disease. Most people with this condition can’t get around well. They spend much of their time in a wheelchair or bed.

Following your healthcare provider’s instructions as closely as possible is very important with calciphylaxis. You should be especially careful when it comes to wound care, keeping any sores or ulcers clean and protected from infection. You should also consult with your provider about any changes to the foods you eat, medication you take, or any new supplements or home remedies you want to try.

Up to 8 out of 10 people with calciphylaxis don’t survive more than a year. Sepsis is the most common cause of death.

Depending on several factors, the one-year survival odds may be higher or lower. Those factors are:

Calciphylaxis is a chronic, lifelong condition because it currently isn’t curable. But it’s possible, in some cases, for the disease to go into remission after treatment. This means your symptoms get better or go away. Researchers don’t know how long it’s possible to keep it in remission.

A rare condition like calciphylaxis can be hard to understand because there’s limited available research and information. Talking to your healthcare provider can help you better understand it and know what to expect. While calciphylaxis may be a complicated and difficult-to-treat condition, there are care options that can help with what you’re going through. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, a counselor may help you sort through your emotions, too.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

If you have a condition that’s affecting your kidneys, you want experts by your side. At Cleveland Clinic, we’ll work with you to craft a personalized treatment plan.