Dysphagia or difficulty swallowing is a symptom of many different medical conditions. These conditions include nervous system and brain disorders, muscle disorders and physical blockages in your throat. Treatment for swallowing issues may include medications, changes to your eating habits and, sometimes, procedures.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/21195-dysphagia-difficutly-swallowing)

Dysphagia is the medical term for difficulty swallowing. When you swallow, many muscles and nerves work together to move food or drink from your mouth to your stomach. When there’s an issue with how these parts work, swallowing may feel uncomfortable or slow. You may cough or choke when you try to swallow water, food or even your own saliva (spit).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Most people know what dysphagia feels like. If you’ve ever eaten too fast and felt like food went down the wrong pipe, or if you’ve cleared your throat because something felt stuck — you’re already familiar with dysphagia. The feeling’s unpleasant, and it’s usually not anything to worry about.

But dysphagia can be a sign of something serious. It’s a common symptom following a stroke. Untreated dysphagia can pose risks like food or liquid getting into your airway (aspiration). This can lead to a lung infection or pneumonia.

A specialist in swallowing disorders called a speech-language pathologist (SLP) can assess your ability to swallow and provide treatment if there’s a risk.

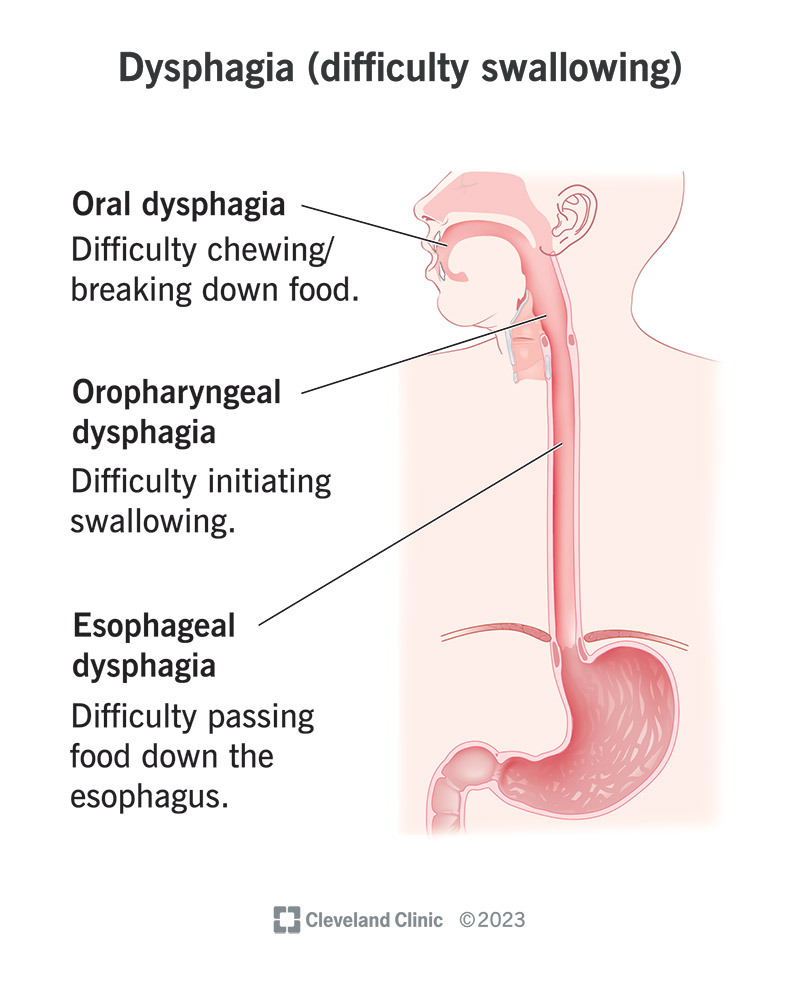

Healthcare providers separate dysphagia into three types based on where the problem is. Think of swallowing as a journey that foods and liquids take to your stomach. There are three main stops along the way: your mouth (oral cavity), throat (pharynx) and the food tube that connects to your stomach (esophagus).

Issues at any of these key stops can create slowdowns, making it difficult or impossible to swallow.

Advertisement

Any disorder, disease or condition that impacts the muscles or nerves that help you swallow can cause dysphagia.

Conditions and injuries affecting your brain and nervous system (the network of nerves that controls muscles and organs) that cause dysphagia include:

Conditions that prevent the muscles in your head and neck from helping you swallow include:

Conditions that create blockages or cause your throat or esophagus to be too narrow can make it hard to swallow. Causes include:

Infections, like strep throat (bacterial tonsillitis), can cause pain and inflammation that lead to dysphagia. Dysphagia can occur after surgery to your head and neck or other types of treatment. For example, radiation therapy for head and neck cancer destroys tumors but can also damage tissue involved in swallowing.

Advertisement

Aging doesn’t cause dysphagia, but it’s a key risk factor. Muscle deteriorates as we get older, making us more susceptible to injury. The risk of developing many neurological conditions associated with dysphagia increases with age.

A healthcare provider will ask about your symptoms and perform a physical exam. They may perform one or more tests to check the structures in your head and neck that help you swallow. Different providers specialize in different tests.

Typical tests include:

Advertisement

Treatment for dysphagia depends on what’s causing it and how severe it is. Your treatment might include:

Many people find rehabilitation helpful. An SLP can teach you exercises to strengthen your swallowing muscles. To swallow safely, your SLP may recommend:

Advertisement

Dysphagia can lead to serious health issues and even be fatal without treatment. Risks include:

Schedule an appointment with your healthcare provider as soon as you notice that your dysphagia isn’t a one-time thing. Recurring dysphagia likely has a cause that your provider can diagnose and treat.

Call 911 or go to the emergency room if you’re having trouble breathing and think something is stuck in your throat. Sudden muscle weakness, paralysis and inability to swallow are also signs of an emergency. Get help right away.

Coughing, choking and the feeling that something’s stuck in your throat may all feel unpleasant, but they can also provide life-saving signals to get help. If you’re regularly struggling to swallow, it’s time for a visit with your healthcare provider. If you’re a stroke survivor or someone considered high risk for a swallowing disorder, your provider will check for swallowing problems. If there’s an issue, an SLP can often provide resources you can use to eat or drink safely, so you get the nourishment you need.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your child has velopharyngeal insufficiency, you want to make sure they’re in the best hands. Cleveland Clinic Children’s is here to help.