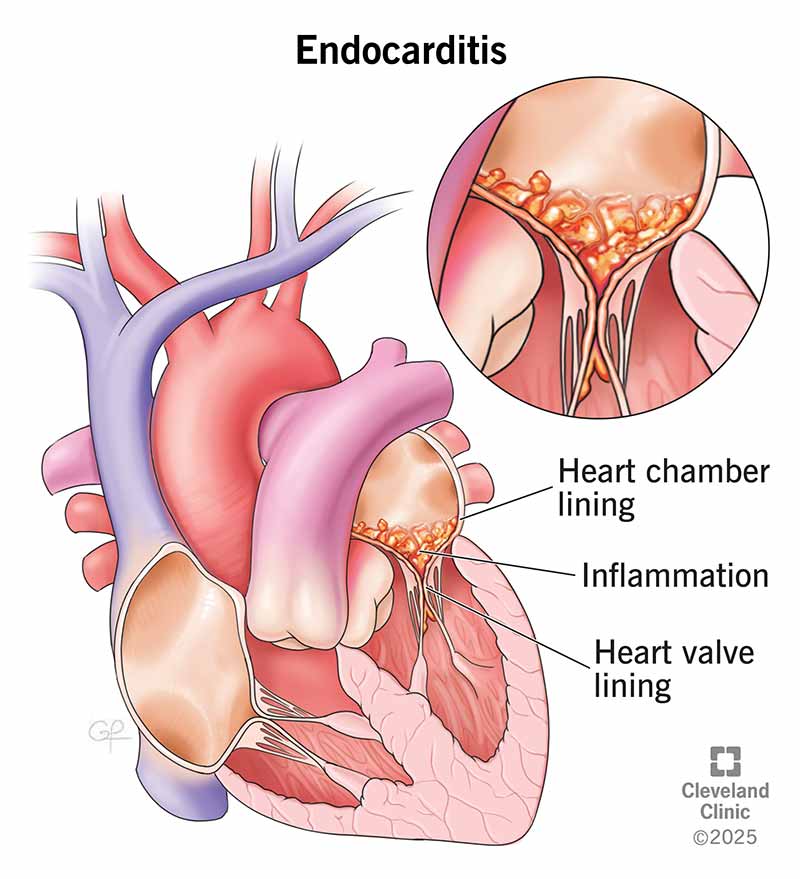

Endocarditis, most often caused by a bacterial infection, inflames the lining of your heart valves and chambers. Symptoms can include chest pain, heart murmur and fast heart rate. Treatment includes several weeks of antibiotics and sometimes surgery. With quick, aggressive treatment, many people survive. Without treatment, endocarditis can be fatal.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/16957-indocarditis-illustration)

Endocarditis is inflammation of the inner lining of your heart valves and chambers (endocardium). Without treatment, endocarditis can be fatal. An infection — often bacterial — is the most common cause of endocarditis. Germs enter your bloodstream and attach to damaged areas in your heart.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Endocarditis involves growths in your heart’s lining called vegetations. As inflammation continues, the vegetations break down the surrounding heart tissue. This can greatly damage your heart valves.

There are two main types of endocarditis: Infective and non-infective.

Infective endocarditis happens when germs (usually bacteria) attach to damaged heart tissue. This is the most common type of endocarditis. Healthcare providers may also call it bacterial endocarditis (BE).

Vegetations in infective endocarditis are made of:

Non-infective endocarditis is much rarer. It involves vegetations in your heart’s lining that aren’t due to an infection. They’re called sterile vegetations.

Non-infective endocarditis is linked with conditions that make your blood clot too easily (hypercoagulable state). Examples of these conditions include antiphospholipid syndrome and lupus (systemic lupus erythematosus).

Healthcare providers may use several other names to describe non-infective endocarditis, including:

Advertisement

Symptoms of infective endocarditis can include:

Go to the emergency room if you have these symptoms. Infective endocarditis is life-threatening.

Infective endocarditis can be:

Non-infective endocarditis typically doesn’t have symptoms. But you’ll likely have symptoms of the underlying condition causing it (like lupus). Most people with non-infective endocarditis don’t know they have it until they get heart imaging tests for other reasons. It may also be a finding in an autopsy.

Most of the time, a bacterial infection causes endocarditis. The bacteria come from elsewhere in your body — like your mouth, skin or respiratory system — and travel through your blood to your heart.

Healthy heart tissue is normally very resistant to infection. But underlying damage can make it more likely for endocarditis to develop. The bacteria attach to and grow on damaged tissue. They grow vegetation and produce enzymes. This destroys surrounding heart tissue.

In general, endocarditis isn’t very common. But certain factors increase your risk for it, like:

Without early diagnosis and treatment, endocarditis can lead to complications like:

If you have symptoms and risk factors for endocarditis, your healthcare provider will want to make a diagnosis as soon as possible.

Diagnostic tests for endocarditis include blood tests, like:

Imaging tests can show vegetations and heart damage. Your provider may recommend one or more of these tests:

Endocarditis can be life-limiting. You’ll need quick treatment to prevent damage to your heart valves and more serious complications.

You’ll likely need IV antibiotics for several weeks — usually up to six — to fully treat the infection. Your provider may adjust the antibiotics once they know which bacteria are at play.

Advertisement

Your provider will check your symptoms throughout your therapy to see if it’s effective. They’ll also repeat your blood cultures.

If endocarditis damages your heart valve and any other part of your heart, you may need surgery.

You can expect to take antibiotics for two to eight weeks to get rid of the infection. Most people survive endocarditis when they get aggressive treatment. But the risk of serious complications or death depends on:

Your healthcare provider can give you a better idea of what to expect based on your situation.

Endocarditis isn’t always preventable. But if you’re at high risk for it or have had it before, your healthcare provider will likely recommend taking prophylactic (preventive) antibiotics before certain dental procedures. These include procedures that involve:

Tell your medical and dental providers you have heart disease that places you at a greater risk for endocarditis. Carry a wallet identification card with you that has specific antibiotic guidelines. The American Heart Association offers these.

Advertisement

With aggressive treatment, most people recover from endocarditis. Know the symptoms of endocarditis and go to the ER right away if you think you have it. Taking good care of your teeth and mouth can lower your risk of endocarditis. That includes daily care, as well as visiting your dental provider regularly.

Advertisement

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

It can be scary and overwhelming when something is happening with your heart valves. Cleveland Clinic heart specialists are ready to get you the help you need.