Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is an autoimmune disease that can cause blood clots and pregnancy complications. Most people with APS need to take blood thinners to prevent future blood clots and miscarriages.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/antiphospholipid-syndrome)

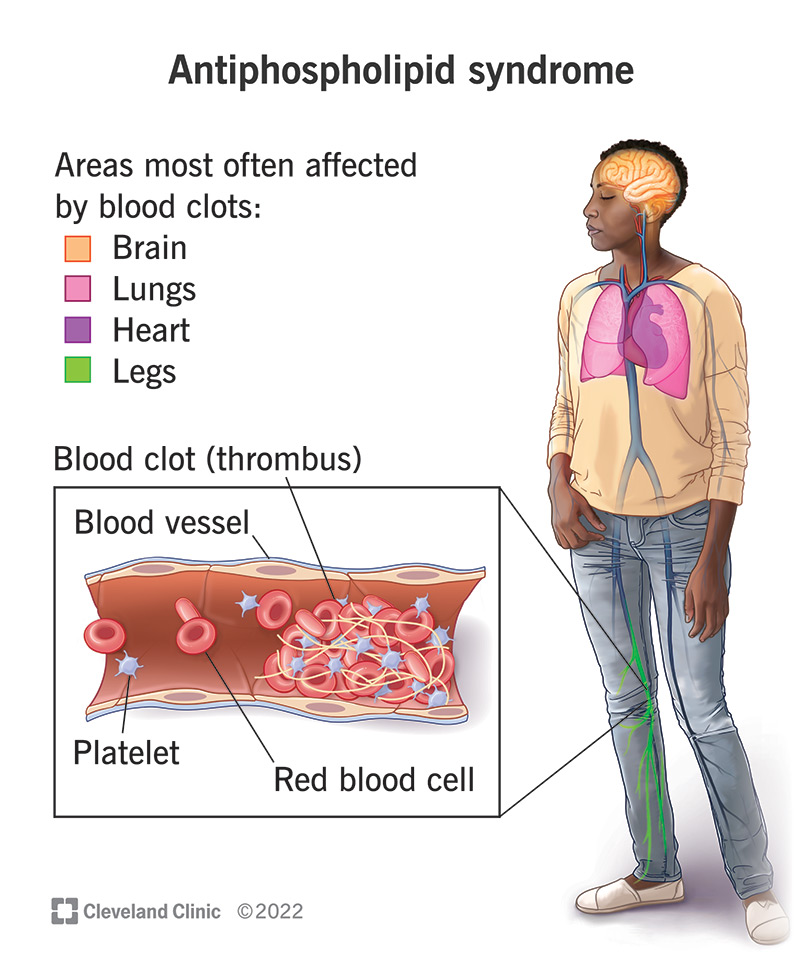

Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) is a condition that makes your body much more likely than usual to form blood clots. Healthcare providers sometimes call it antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The blood clots from APS can cause severe, life-threatening complications like strokes. They can also make it more likely to experience miscarriages and other pregnancy complications.

APS is an autoimmune disease. Autoimmune diseases happen when your immune system accidentally attacks your body instead of protecting it.

Some people with antiphospholipid syndrome notice mottled skin (livedo reticulitis) with a darkened, lace-like pattern. But most people with APS don’t experience any noticeable symptoms until they have a blood clot or experience a pregnancy complication.

Symptoms of a blood clot can include:

Blood clots can be life-threatening emergencies. Go to the emergency room right away if you think you have a blood clot.

APS symptoms you might not be able to see, feel or notice can include having:

Antiphospholipid syndrome happens when your immune system accidentally starts making certain abnormal antibodies. Usually, your immune system makes and uses antibodies to protect you. They’re special proteins that act like an army of security robots that find and destroy germs, allergens or toxins in your blood. When your immune system detects a new unwanted substance in your body, it makes antibodies customized to find and destroy that invader.

Advertisement

Antiphospholipid syndrome gets its name from how your immune system attacks your body. If you have APS, your immune system makes antibodies that attack proteins bound to phospholipids (a type of fat cell). These attacks damage the phospholipids and make them more likely to clump together and form clots.

The three antibodies that can cause APS include:

People with APS have one, two or all three of these antiphospholipid antibodies. It’s also possible to have antiphospholipid antibodies and never have signs or symptoms of APS. Even though experts know they cause APS, they aren’t sure what triggers your immune system to start making these faulty antibodies.

Anyone can develop APS, but you may be more likely to if you:

Antiphospholipid syndrome can cause severe, potentially fatal complications.

The most severe APS complications happen when blood clots block blood vessels throughout your body, including in your:

If you’re pregnant, APS may cause a miscarriage if a clot blocks the flow of nutrients in your placenta. It can also increase your risk of preeclampsia.

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is an APS complication that causes multiple blood clots to form in different organs throughout your body within a few days of each other. CAPS is fatal in almost half of people who experience it. Fewer than 1% of people with APS develop CAPS.

APS doesn’t usually affect how long you’ll live (your life expectancy). It can cause fatal complications if you experience a blood clot that blocks a blood vessel in one of your organs, especially if you have CAPS.

Most people are only tested for APS after a blood clot or miscarriage. Some people have antiphospholipid antibodies but never experience APS symptoms or complications.

A healthcare provider will diagnose APS with blood tests.

Your provider will take samples of your blood for three different blood tests — one test that screens for each of the three antiphospholipid antibodies. At least one of the blood tests must come back positive for APS two different times three months or more apart for you to be diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome.

Advertisement

Your provider will suggest treatments that lower your risk of having a blood clot. The most common treatments include anticoagulant medications (blood thinners), including:

Your provider might recommend medications to prevent miscarriages if you’re pregnant and have APS, including:

These treatments are safe if you're pregnant and shouldn’t harm you or the fetus.

Advertisement

Taking blood thinners increases your chances of bleeding (both internally and outside your body).

Contact your healthcare provider right away if you experience any of the following symptoms:

APS responds well to treatment with blood thinners, and you should be able to do all your usual activities once you start treatment. Most people managing APS with blood thinners can safely get pregnant and have biological children.

APS doesn’t usually go away. You may never have a clot or experience complications, but you’ll probably need to take blood thinners for the rest of your life.

Because experts aren’t sure what makes your body produce the antiphospholipid antibodies that cause it, there’s no way to prevent APS.

The most important part of living with APS is preventing blood clots. Taking blood-thinning medication is a big part of that prevention.

Managing other health conditions that can increase your clot risk is also important. Talk to your provider about your unique clot risks if you have:

Advertisement

Smoking also increases your risk of blood clots, especially if you have a clotting disorder like APS.

People who take estrogen therapy (for birth control or during menopause) also have an increased clot risk.

People with APS don’t usually need to follow a special eating plan. The same kinds of food that help you maintain good overall health should help support your body if you have APS.

You may need to monitor how much vitamin K you eat if you take warfarin. Suddenly eating a lot of foods high in vitamin K (like leafy greens) when you usually don’t can increase your clot risk. Talk to your provider about any foods you should avoid.

Ask your provider how much alcohol is safe for you to drink. Alcohol thins your blood, and this effect can be increased when you’re taking blood thinners.

You’ll need to see your provider regularly to make sure your blood is still able to clot safely if you get a cut or bruise.

Antiphospholipid syndrome can increase the risk of pregnancy-related complications. Talk to your healthcare provider if you’re concerned about any risks or pregnancy complications you might experience.

Go to the ER right away if you:

It may be helpful to ask your provider:

Although part of the testing for APS is called “lupus anticoagulant,” your healthcare provider isn’t specifically testing for lupus when ordering tests for APS. Some people with lupus also have APS, which is where this term originated.

Antiphospholipid syndrome can feel like a ticking clock inside your body that you can’t see or feel until it causes a blood clot. It’s scary, but it’s manageable. Having a condition (even a serious one) doesn’t define who you are. Most people taking blood thinners are able to do everything they want to in life — including having biological children.

Talk to your healthcare provider about what to watch for, how you can prevent clots and what to do if you experience one.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic's health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability, and up-to-date clinical standards.

Living with a noncancerous blood disorder can be exhausting. But there’s hope. Cleveland Clinic’s classical hematology experts provide personalized care and support.