Eye cancers start in the cells inside your eyeball and in nearby structures, like your eyelids and tear ducts. All forms of eye cancer are extremely rare. The most common types include uveal melanomas, which start in the middle of your eye (uvea) and retinoblastoma. Treatments include a type of radiation therapy called brachytherapy, as well as surgery.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/17292-eye-cancer)

Eye cancer includes several rare types of cancers that begin in your eye, including your eyeball and the structures surrounding your eyeball. Eye cancer starts when cells multiply out of control and form a tumor. Tumors can be benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Unlike benign tumors, malignant tumors can grow and the cancer can spread throughout your body.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Diagnosing and treating eye cancers early can often prevent the spread.

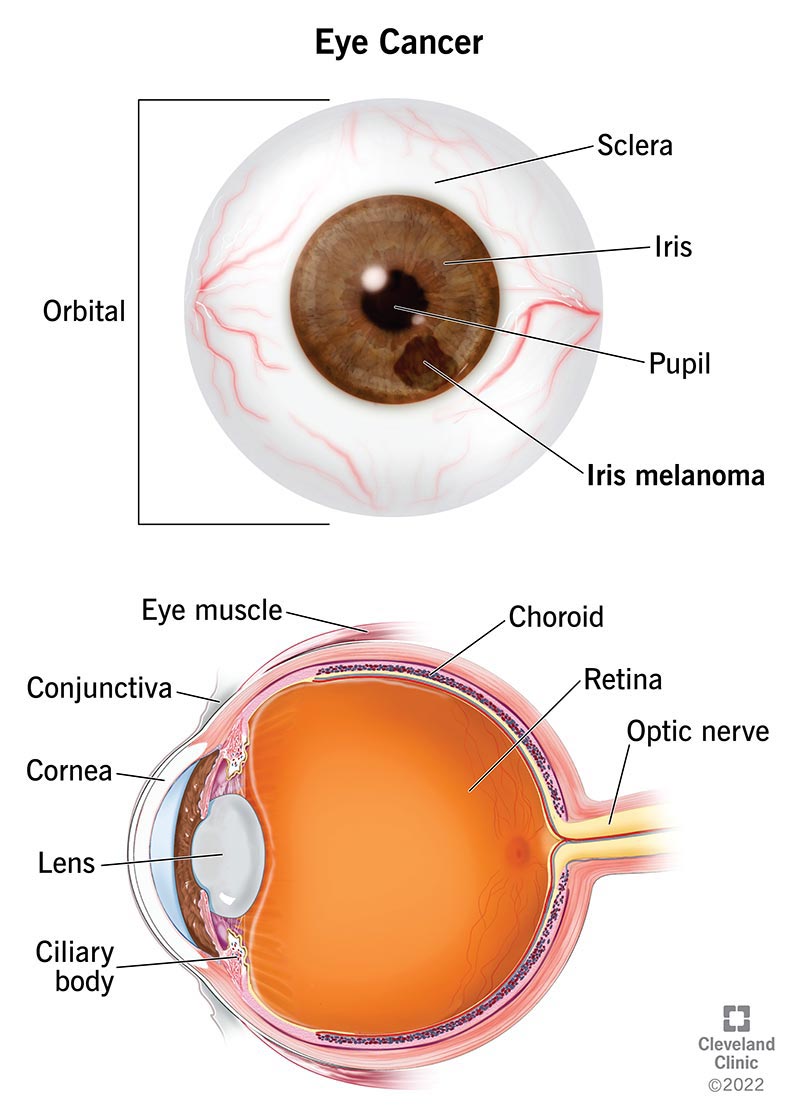

Healthcare providers categorize eye cancers based on where cancer starts, its location in your eye and the types of cells.

Intraocular melanoma arises from cells called melanocytes, the same type of cell involved in the most serious form of skin cancer (melanoma). Most eye cancers are melanomas. Most form in the middle part of your eye (uvea). They’re called uveal melanomas. They include:

Melanomas sometimes form in the conjunctiva, the membrane that covers the front part of your eyeball. They’re called conjunctival melanomas. They’re incredibly rare. Like uveal melanomas, they tend to spread and are aggressive.

Advertisement

Orbital and adnexal cancer form in the tissues close to your eyeball. Orbital cancers form in your orbit, or the tissues, muscles and nerves that move your eyeball. Adnexal cancer forms in supporting tissues, including your eyelids and tear glands. Healthcare providers classify them according to the type of cell that transforms into cancer.

Most are:

Retinoblastoma is a malignant tumor arising from the retina in the back of your eye. They’re most common in children under age five.

Intraocular lymphoma is a rare form of B-cell lymphoma. It forms in white blood cells called lymphocytes. It’s most common in people who are older than 50 or who have weakened immune systems. Many people with this form of eye cancer also have primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL). PCNSL is a cancer that may affect various parts of your central nervous system, including your brain, spinal cord and spinal fluid.

Eye cancer is extremely rare. Only about 3,400 people in the United States receive an eye cancer diagnosis each year. It’s more common for cancers to start in other parts of your body and spread to your eye. Because they don’t start in your eye, providers don’t consider these cancers eye cancer.

Intraocular melanomas are by far the most common form of eye cancer. Most start in the middle part of your eye in a structure called the choroid. Approximately 2,500 people in the United States receive this diagnosis each year.

Many people with eye cancer don’t experience symptoms unless a tumor is growing in a location that interferes with how their eye works. Experiencing symptoms doesn’t mean you have eye cancer. Many benign (noncancerous) eye conditions share symptoms with eye cancer. See a healthcare provider to know for sure.

The most common symptom of eye cancer is painless vision loss. Other vision problems that may be signs of eye cancer include:

Other signs and symptoms include:

Most people don’t learn they have eye cancer until a healthcare provider, like an optometrist or ophthalmologist, notices something suspicious during an eye exam. For example, enlarged blood vessels in your eye or a dark spot may signal eye cancer or another eye condition. You’ll need tests to be sure.

Advertisement

As with cancers in general, eye cancer occurs when cells begin to divide and multiply out of control, eventually forming a mass called a tumor. Pieces of the tumor can break off and spread to your lymph nodes and bloodstream. The cancer cells can travel to other parts of your body via your bloodstream and lymphatic system, causing new tumors to form in other organs. When this happens, healthcare providers say that your cancer has “spread” or “metastasized.” It’s a sign of a more advanced disease.

Scientists are still researching to understand what causes otherwise healthy cells to become cancer cells.

Researchers have identified several risk factors that may increase your likelihood of developing eye cancer:

Advertisement

An eye disease specialist (ophthalmologist) or an ocular oncologist diagnoses eye cancer. They may perform a variety of procedures to rule out other, more common eye conditions before arriving at a cancer diagnosis.

During an eye exam, a healthcare provider examines your eye closely, looking for signs of cancer. They may look for dark spots and enlarged blood vessels. They may check to see if your eyeball is moving as it should. They may use special tools to see the structures in your eye more clearly.

The results of imaging procedures and the information from your eye exam are often enough to diagnose eye cancer. Common imaging procedures include:

Advertisement

You may need additional imaging procedures if your provider suspects the cancer’s spread. Imaging procedures that can show if cancer’s spread to parts outside your eye include:

During a biopsy, a healthcare provider removes a sample of tissue from the tumor and tests it for cancer cells. Healthcare providers can identify most eye cancers with a physical exam and imaging. Still, a biopsy can provide information about the makeup of your cancer cells, including genetic mutations (changes) that make them unique. Your provider can use this information to determine characteristics about your cancer, like how aggressive it is. It can also show if you’re eligible for certain treatments.

Cancer staging helps providers determine how advanced cancer is. They use this information to plan treatments and gauge your prognosis, or the likely outcome of your condition.

There are two common staging systems for eye cancer:

Providers stage cancer by assessing various factors.

They consider this information together to assign eye cancer a stage between I and IV, with I being the least advanced and IV meaning the cancer’s more advanced.

Another common system stages cancer based on tumor size. Size influences the type of treatments that will likely work best. Measurements are in millimeters (mm).

Your provider may recommend liver imaging scans if they suspect your cancer’s spread. Your liver is the most common place for eye cancer to spread outside of your eye.

For slow-growing tumors or if the diagnosis isn’t certain, your provider may recommend monitoring your condition and delaying treatment — especially if treatment risks outweigh the benefits. For example, you may want to delay treatment if treating an area could cause vision loss.

Radiation therapy is one of the most common treatments for eye cancer.

Surgery is a common treatment option, especially for small tumors that haven’t spread beyond your eyeball. Procedures include:

Laser therapy uses heat to destroy eye cancer. The most common type is transpupillary thermotherapy (TTT). During the procedure, infrared light delivers concentrated heat toward the tumor, destroying cancer cells. Providers may use this on its own or after brachytherapy to prevent cancer from returning (recurring).

Immunotherapy treatments help your immune system identify and destroy cancer cells more effectively. In certain instances, providers use the immunotherapy drug tebentafusp to treat uveal melanoma. Immunotherapy is a common treatment for cancer that’s spread or that providers can’t surgically remove.

Targeted therapy drugs target specific weaknesses in cancer cells, destroying them. You may be eligible for targeted therapy treatments if cancer cells contain a BRAF gene mutation (change). Currently, this mutation is more common in skin melanomas, but this treatment may be beneficial in people with eye melanomas, too.

Chemotherapy isn’t a common treatment for eye cancer, but your healthcare provider may recommend it if your cancer hasn’t responded to other treatments or if it spreads to other areas.

Side effects depend on the type of treatment your provider recommends. As these treatments target your eye, it’s possible that you’ll experience vision changes. One of the most significant risks is partial or complete vision loss. These risks depend on multiple factors that you should discuss with your provider.

Your prognosis, or likely treatment outcome, depends on many factors, including the tumor’s size, location and how much it’s spread. For example, brachytherapy eliminates 95% of small and medium intraocular melanomas. Eye cancer may not be curable. However, its growth within your eyeball can be contained.

Ask your healthcare provider about your prognosis based on your specific type of eye cancer.

Survival rates communicate information about how many people with a certain cancer diagnosis are alive five years after their diagnosis when compared to people without the same diagnosis. The survival rates for the most common form of eye cancer, intraocular melanoma, are excellent when a provider diagnoses and treats the cancer when it’s still in your eyeball. The survival rates aren’t as good if the cancer’s spread to other organs.

Fortunately, providers diagnose and treat most cancers before they’ve metastasized.

There’s no way to prevent eye cancer. Still, you can improve your prognosis by getting screened if you know that you’re in a high-risk group for getting eye cancer. For example, you may consider regular exams if you have BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome. If you have a family history of retinoblastoma and have a child, it’s a good idea to get them regular eye exams to screen for cancer.

Questions you may ask include:

An eye cancer diagnosis can mean many things depending on the type of cancer you have, its location in your eye and whether it’s spread. With the most common types of eye cancer, treatment success depends on early diagnosis. This is why regular eye exams are so important. As most eye cancers don’t cause symptoms in the early stages, irregular findings during an eye exam are usually the first sign of eye cancer. Follow your vision care provider’s guidance on how often you need regular eye exams to detect vision problems and other conditions that may affect your eyes.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When you’re diagnosed with eye cancer, you’re probably wondering what’s next. Cleveland Clinic’s ophthalmic oncology providers personalize treatment just for you.