Immunotherapy for cancer uses your body’s immune system to find and destroy cancerous cells. There are several different immunotherapy types, but all immunotherapy works by training your immune system to do more to fight cancer. Current immunotherapies can’t cure cancer, but they may help some people with cancer live longer.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/11582-immunotherapy)

Immunotherapy is cancer treatment that boosts your immune system so it’s better at fighting cancer. Your immune system’s job is to protect you from intruders, ranging from allergens and germs to cancer cells. It has immune cells that constantly patrol your body and destroy invaders that pose a threat.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

But cancer is good at dodging your immune system’s defenses.

Immunotherapy trains your immune system to find and kill more cancer cells. It helps your body produce more cancer-fighting immune cells.

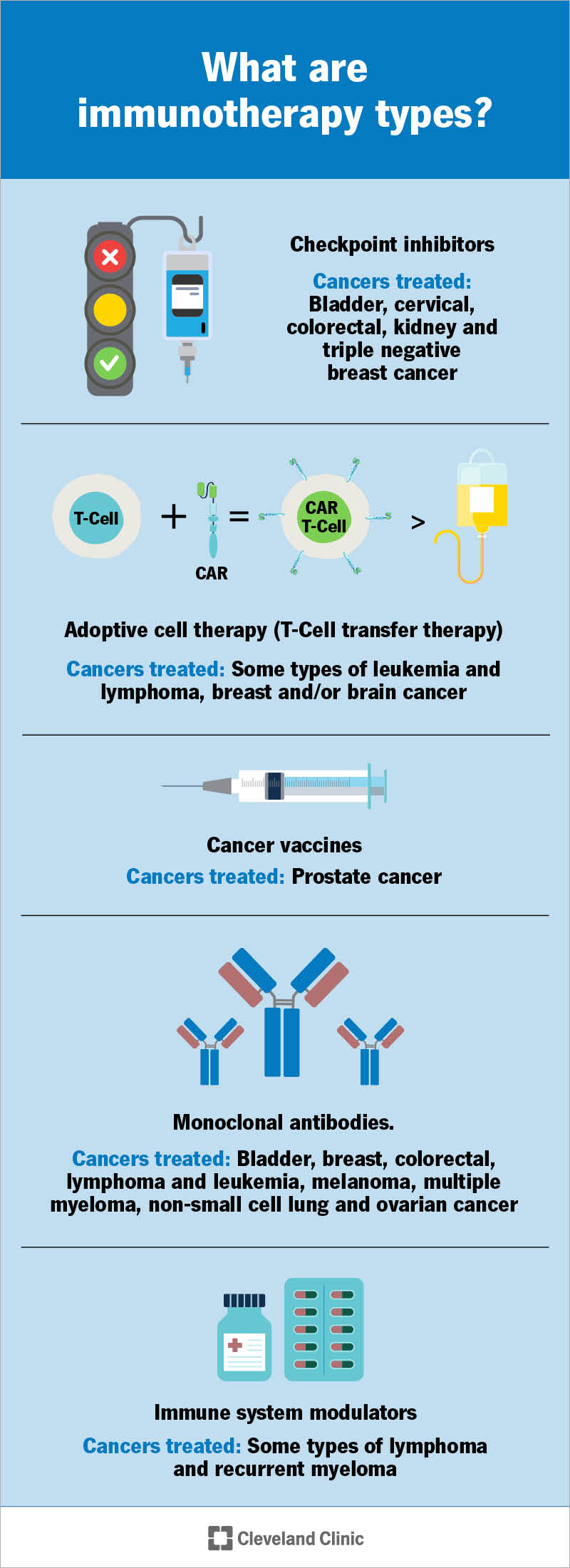

Types of immunotherapy drugs used for cancer include:

Checkpoint inhibitors help immune cells called T cells fight cancer for longer.

Your T cells are powerful fighters — sometimes, too powerful. They can fight so hard that they damage healthy cells. To keep this from happening, your body has checkpoint proteins. They manage the flow of signals that tell T cells when to turn on (fight) or off (stand down). (Think of checkpoint proteins as traffic monitors that manage traffic flow by switching traffic lights off and on.) Turning T cells off keeps them from overreacting and damaging healthy cells.

But these checkpoints can also help cancer cells escape your T cells. Immunotherapy drugs stop checkpoint proteins from telling your T cells to turn off. That way, T cells keep fighting cancer.

Adoptive cell therapy changes your T cells in a lab. Here are the two main treatment types and what’s involved:

Advertisement

Monoclonal antibody therapy for cancer uses lab-made antibodies that fight cancer in many ways. Some work by blocking proteins that cancer cells need to grow. Others flag cancer cells for destruction. Some monoclonal antibodies inject toxic or radioactive material into cancer cells, killing them.

Healthcare providers also consider monoclonal antibody therapy a form of targeted therapy. This cancer treatment targets cancer cell weaknesses to stop tumors from growing.

Cancer vaccines are different from vaccines that prevent infections. This includes vaccines that prevent cancer-related infections. For example, the HPV vaccine protects against HPV infections that cause cervical cancer. The hepatitis B vaccine prevents infection that can lead to liver cancer.

Cancer vaccines used as immunotherapy treatments don’t prevent cancer. Instead, they fight cancer you already have. They train your immune system to recognize identifying markers on cancer cells. Once immune cells identify the markers, they attack.

Immunomodulators boost your body’s immune response in many ways. There’s so much variety in how they work that they’re also called “nonspecific immunomodulating agents.” Here’s how different immunomodulators work in cancer treatment:

You may receive immunotherapy alone or in combination with other cancer treatments. Treatment may happen daily, weekly, monthly or in a cycle. With cyclic immunotherapy, you take a rest period after treatment. The break gives your body time to produce healthy cells.

Advertisement

People receive immunotherapy for cancer in different ways. You may get:

Immunotherapy can’t cure cancer. But it helps some people with cancer live longer. Oncologists often recommend immunotherapy for cancers that have spread, come back after treatment or haven’t responded to other therapies.

Unlike chemotherapy, immunotherapy doesn’t use toxic drugs that harm cancer cells, as well as healthy ones. Instead, immunotherapy uses drugs that help your own immune system target cancer cells. This can lead to less cell damage and fewer side effects. This is why immunotherapy is considered one of the most promising new types of cancer treatment available.

But immunotherapy doesn’t work on every type of cancer or for everyone who gets this treatment. And immunotherapy side effects do occur. They range from mild to severe, depending on the drug.

It’s important to work closely with your oncologist to weigh all the pros and cons before starting immunotherapy.

Advertisement

Call your oncologist if you have side effects during or after treatment that are more serious than expected. You should also reach out whenever you have questions about your treatment. Questions to ask may include:

Immunotherapy for cancer is one of the most promising cancer treatments — and for good reason. It uses your body’s defenses to mount stronger attacks against cancer. Targeting cancer this way can potentially kill tumor cells without damaging your healthy cells.

But there are still lots of challenges to overcome. Even with immunotherapy, cancer remains really good at evading your immune system’s defenses. After a while, treatment often stops working. Experts are working hard to develop immunotherapy drugs that fight cancer better for longer. As they do, we’ll likely see more immunotherapies that can treat more cancer types with even better results.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Immunotherapy can take cancer treatments to new, powerful heights. And Cleveland Clinic is here to help with the latest advances.