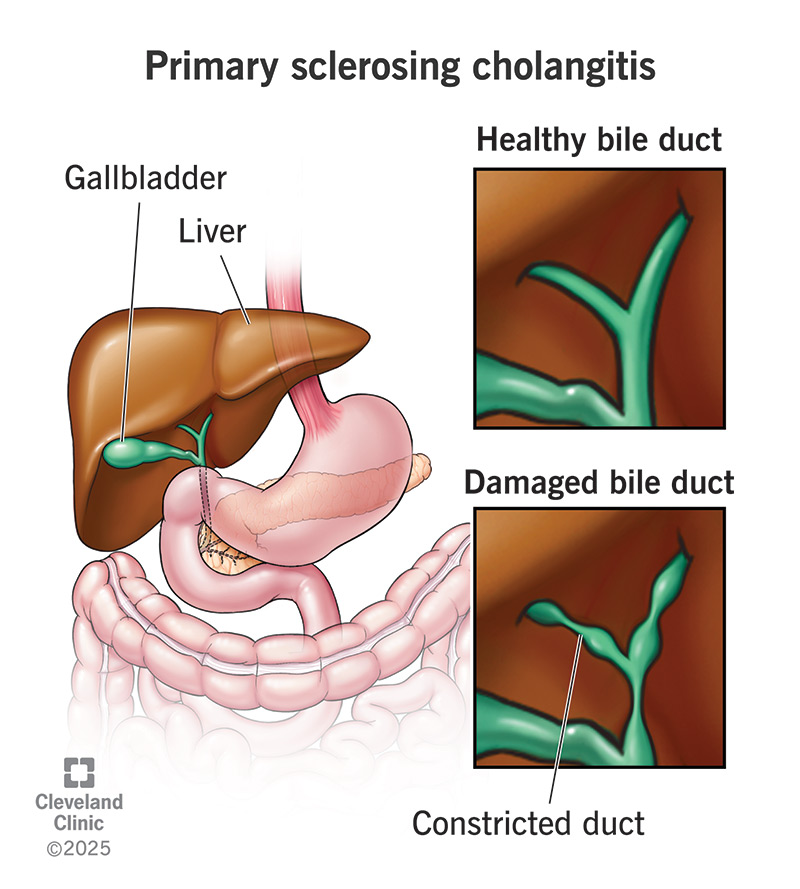

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a disease that damages your bile ducts and liver. It makes your bile ducts narrow, which eventually causes bile to back up into your liver. PSC may not initially cause any symptoms. It can lead to cirrhosis and liver failure. A liver transplant is the only treatment to cure the condition.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/23569-primary-sclerosing-cholangitis.jpg)

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) (pronounced “SKLEH-roh-sing” “koh-lan-JI-tis”) is a disease that affects your bile ducts, which are the tubes that carry bile from your liver to other organs in your digestive system. It causes chronic swelling and irritation there (inflammation), which healthcare providers call cholangitis. Eventually, this can cause scarring.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

When scar tissue forms in your bile ducts, there’s less room for bile to flow through them (biliary stricture). When bile can’t flow, it backs up and gradually damages your liver. Within 10 to 15 years, this can lead to liver failure. You can’t live without a liver. While there are temporary treatments, there is currently no cure for PSC, except for a liver transplant.

While you might not have symptoms at first, PSC gets worse over time. When the flow of bile slows (cholestasis), it can leak bile toxins into your blood. This can eventually make you very sick. Treatment can help you manage symptoms until a liver transplant is available.

Healthcare providers categorize PSC into stages. The stages mainly refer to how much scar tissue (or fibrosis) has formed in your liver. There are four stages:

The symptoms of PSC change as the disease progresses. Up to 50% of people may have no symptoms at all at the time of diagnosis. PSC is often found by accident when testing for other conditions. The first symptoms might be vague. They may include:

Advertisement

As the disease worsens, your symptoms may include:

It’s not entirely clear what causes PSC, but it appears to involve a combination of factors, including:

Healthcare providers believe that PSC may be a type of autoimmune disease. Inflammation is one of the tools of your immune system. It’s supposed to be a response to an attack, but when inflammation becomes chronic, it tends to be a sign of disease.

Experts have also noticed that people who have PSC are prone to other autoimmune diseases, including:

Certain environmental factors (like exposure to unsafe toxins) may trigger an autoimmune response in some people.

No, PSC isn’t related to drinking beverages containing alcohol.

Risk factors for primary sclerosing cholangitis include:

Some of the more common complications of primary sclerosing cholangitis include metabolic dysfunction, infection and an increased risk of cancer. But this disease gets worse slowly. As your bile ducts and liver become increasingly scarred, their functions begin to fail.

When your bile ducts become significantly blocked, they won’t be able to deliver bile to your small intestine to help with digestion. Bile is necessary to help break down fats in your intestines and absorb fat-soluble vitamins. Without it, your digestive system may have trouble processing fats, and you may not be able to absorb these essential vitamins from your food. This can lead to a variety of additional complications, including:

Liver damage due to cirrhosis can reduce blood flow to your portal vein. This can cause pressure to build up in the veins around your digestive system, including veins in your esophagus and abdomen. These swollen veins can rupture, leading to internal bleeding.

Blocked bile ducts make you more likely to get infections, which may cause fever, abdominal pain, blood infection or sepsis. This usually requires hospitalization with IV antibiotics, as it can be life-threatening.

Advertisement

Advanced PSC leads to an increased risk of developing several cancers, including:

Healthcare providers often find PSC by accident while testing for something else. Early signs of the disease may show up on a blood test or imaging test. A blood test may show high levels of alkaline phosphatase or indicate an immune response is happening. Having high white blood cells is usually a sign of infection in your liver.

To confirm the disease, your healthcare provider may suggest a more specific test, like:

Currently, there isn’t a treatment that can slow or stop primary sclerosing cholangitis from getting worse. But you can treat some of the symptoms and complications. For example, your healthcare provider may prescribe:

Advertisement

Your healthcare provider will also keep an eye on your liver and bile ducts. As the disease progresses, they may be able to open a blocked bile duct. They can do this through an ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography), a type of endoscopy.

This involves a gastroenterologist passing tiny instruments through a tube to treat your bile ducts. Your provider can open your bile duct with a balloon or prop it open with a stent. If ERCP isn’t possible, then they obtain access directly through the skin (percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiography).

This is a temporary solution, though. Over the course of 10 to 20 years, primary sclerosing cholangitis eventually progresses from early to late-stage liver disease, and finally, liver failure. Your healthcare provider will monitor your liver damage to determine when you should begin to consider liver transplantation. You’ll need to pass certain qualifications to get on a liver transplantation waiting list.

After diagnosis, the average life expectancy is about 10 to 20 years. A liver transplant can give you a new lease on life. But in up to 1 in 5 cases, PSC may return after a liver transplant. When this happens, the new liver may fail. The average life expectancy in this case is about nine months.

Advertisement

Another factor that can affect life expectancy is cancer. If cancer develops as a complication of PSC, you may not be a good candidate for a liver transplant. In carefully selected cases, healthcare providers may attempt to treat cancer first with radiation or chemotherapy and then try a liver transplant.

There are things you can do to help manage the fatigue that’s common with PSC and prevent additional damage to your liver. For example:

PSC may not cause any symptoms in the early stages. But you may begin feeling sick as the disease gets worse. Contact your healthcare provider if you have any of the following symptoms, especially if you have an inflammatory bowel disease like ulcerative colitis:

“Primary” means that this disease is the original cause of inflammation and scarring of your bile ducts. There’s no other cause but the disease. In secondary sclerosing cholangitis, inflammation and scarring of your bile ducts are caused by something else. Some causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis include:

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare and unpredictable condition that you can’t prevent. It gets worse so gradually that you might not notice symptoms at first. This uncertainty can be hard. But remember, you’re not alone in this journey. Visiting your healthcare provider for routine screenings can play a key role in managing this condition. You may be able to detect changes early, before they start impacting your everyday life.

Remember, it’s OK to feel scared and overwhelmed right now. But with time, support and the right medical care, you can find the strength to navigate this new path.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic providers compassionately diagnose and treat all liver diseases using advanced therapies backed by the latest research.