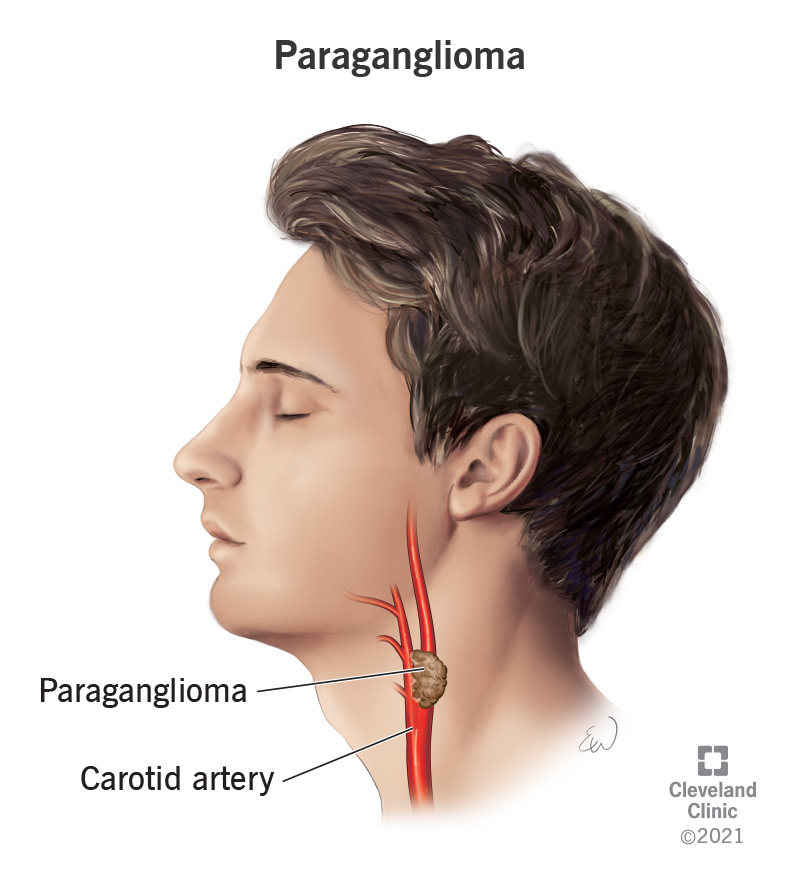

A paraganglioma is a rare but treatable neuroendocrine tumor that usually forms along major blood vessels and nerve pathways in your neck and head. In most cases, the tumor is benign, but it can be malignant (cancer). Symptoms include high blood pressure and headaches, though you could experience no symptoms.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22394-paraganglioma)

A paraganglioma (also known as an extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma) is a rare neuroendocrine tumor (NET) that forms near your carotid artery (the major blood vessels in your neck), along nerve pathways in your head and neck and in other parts of your body. The tumor is made of a certain type of cell called chromaffin cells, which produce and release certain hormones known as catecholamines.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Your adrenal glands, the two glands that are on top of each kidney, make several hormones. Among these are hormones called catecholamines that help control the following important bodily functions:

The primary catecholamines include:

Even though paragangliomas don’t form in your adrenal glands, they’re made of tissue that’s found in your adrenal glands. Paragangliomas may release extra catecholamines into your blood, causing certain signs and symptoms.

Paraganglioma and pheochromocytoma are both rare tumors that form from the same type of cells known as chromaffin cells. The difference is where they form in your body.

Pheochromocytomas form in the center of your adrenal gland (adrenal medulla), and paragangliomas form outside your adrenal gland, usually along the arteries or nerves in your neck. Paragangliomas are also called extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas.

Paragangliomas can be benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer). Approximately 20% of paragangliomas are malignant.

It can be very challenging for healthcare providers to tell if a paraganglioma is cancerous or not — even after they’ve looked at the tumor tissue under a microscope after it’s been removed. Because of this, a paraganglioma is often considered cancer if it has:

Advertisement

There’s no standard staging system for paraganglioma if it’s cancerous. Instead, it’s described as the following:

Paragangliomas usually grow very slowly. But this could vary from case to case.

Anyone at any age can get a paraganglioma, but they occur most often in people between 30 and 50 years of age. Approximately 10% of cases occur in children.

Paraganglioma is a rare tumor. It’s estimated that only 2 out of every 1 million people have paraganglioma.

Signs and symptoms of paraganglioma happen when the tumor releases too much adrenaline or noradrenaline into your blood. However, some paraganglioma tumors don’t make extra adrenaline or noradrenaline and don’t cause symptoms (are asymptomatic). Common symptoms of paraganglioma include episodes of:

Less common symptoms of pheochromocytoma include:

Some people who have a paraganglioma may experience symptoms infrequently or in bursts.

In most cases of paraganglioma, the exact cause is unknown, and it occurs randomly. Approximately 25% to 35% of people who have paraganglioma have a hereditary condition (passed through the family) that’s linked to paraganglioma, including:

Since paraganglioma is a rare tumor and is sometimes asymptomatic, it can be difficult to diagnose. Healthcare providers sometimes find paragangliomas when they order a test or procedure for another reason.

Advertisement

A provider may suspect a diagnosis of paraganglioma after reviewing the following factors:

Your healthcare provider may use the following tests and procedures to diagnose paraganglioma:

Advertisement

After your provider has diagnosed you with paraganglioma, they’ll likely perform additional tests to see if it has spread to other parts of your body.

If you’re diagnosed with paraganglioma, your provider will likely recommend genetic counseling to find out your risk for having an inherited syndrome and associated cancers.

Your healthcare provider may recommend genetic testing if any of the following situations apply to you:

If your genetic counselor finds certain gene changes in your testing results, they will likely recommend that your family members who are at risk but don't have signs or symptoms be tested as well.

Treatment options for paraganglioma depend on several factors, including:

Advertisement

If you have a paraganglioma that causes symptoms due to excess adrenal hormones, your healthcare provider will likely recommend medication to manage the symptoms. Medications may include:

Treatment options for paraganglioma include:

Together, you and your healthcare team will determine a treatment plan that works best for you and your situation.

Surgery is the main form of treatment for paragangliomas. During the surgery to remove the tumor, your surgeon will check the surrounding tissue and lymph nodes to see if the tumor has spread. If it has, your surgeon will remove the affected tissue(s) as well, if possible.

Most paragangliomas can be removed using minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopic surgery, which involves making a few small incisions in your skin and removing the tumor with special instruments. However, traditional open surgery may be needed for large tumors.

After surgery, your provider will check your catecholamine levels in your blood or urine. Normal catecholamine levels are a sign that all the paraganglioma cells were removed.

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that focuses strong beams of energy to destroy cancer cells or keep them from growing while sparing as much surrounding healthy tissue as possible.

There are two types of radiation therapy:

The type of radiation therapy your provider may recommend depends on whether your cancer is localized, regional, metastatic or recurrent. Providers most often use external radiation therapy and/or 131I-MIBG therapy to treat malignant paraganglioma. The treatment 131I-MIBG is a radioactive substance infusion that collects in certain kinds of tumor cells, killing them with the radiation that it gives off.

Chemotherapy is the standard therapy for treating metastatic paraganglioma. It’s a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells by killing the cells or by preventing them from dividing and multiplying. Chemotherapy is usually given through a vein (intravenously). It’s usually an effective treatment, but it can cause side effects.

Ablation therapy is a minimally invasive treatment option that uses very high or very low temperatures to destroy tumors. Ablation therapies that can help kill cancer cells and abnormal cells include:

Targeted therapy is a treatment option that uses medications or other substances to attack specific cancer cells without harming healthy cells. Healthcare providers use targeted therapies to treat metastatic and recurrent paraganglioma.

Researchers are currently studying sunitinib, a type of tyrosine kinase inhibitor, for treatment for metastatic paraganglioma. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy is a type of targeted therapy that prevents tumors from growing.

The prognosis (outlook) for paraganglioma varies depending on certain factors, including:

People who have a small paraganglioma that has not spread to other parts of their body (has not metastasized) have a five-year survival rate of about 95%. People who have paraganglioma that has come back after initial treatment (recurred) or spread to other parts of their body (metastasized) have a five-year survival rate between 34% and 60%.

There are also cases of aggressive paraganglioma tumors that haven’t metastasized but have invaded local tissue to the point where surgery can’t fully remove it. In these cases, the excess release of adrenaline and noradrenaline can be dangerous and difficult to treat.

If paragangliomas are left untreated, whether benign or malignant, they can potentially cause serious, life-threatening complications due to the excess amounts of adrenaline and noradrenaline they can secrete. Complications can include:

Unfortunately, you can’t prevent developing a paraganglioma. However, if you’re at risk for developing a paraganglioma due to certain inherited syndromes and genes, genetic counseling can help screen for paraganglioma and potentially catch it in its early phases.

Talk to your healthcare provider if you have any first-degree relatives (siblings and parents) that have been diagnosed with paraganglioma or pheochromocytoma and/or any of the following genetic conditions:

If you’ve been diagnosed with paraganglioma and experience concerning symptoms, contact your healthcare provider.

If you’re experiencing symptoms of paraganglioma, such as high blood pressure and headaches, talk to your provider. Even though paraganglioma is rare and the likelihood of having it is low, it’s important to treat high blood pressure regardless.

If you’ve recently found out that one of your first-degree relatives (siblings and parents) has a genetic syndrome, such as multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 syndrome or von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease, that puts you at a higher risk of developing a paraganglioma, ask your provider about genetic testing.

If you’ve been diagnosed with a paraganglioma, it may be helpful to ask your healthcare provider the following questions:

While most paraganglioma cases have an unknown cause, there’s a significant link to certain inherited conditions. If you or one of your first-degree relatives have been diagnosed with paraganglioma or pheochromocytoma, it’s important to go through genetic testing to make sure you don’t have a genetic condition that could potentially cause other medical issues. If you have any questions about your risk of developing a paraganglioma, talk to your healthcare provider. They’re there to help you.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Hormonal conditions can be tricky to find and complicated to treat. The experts in endocrinology at Cleveland Clinic are here to provide the best care.