Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a name for inherited blood disorders due to a change in the HBB gene. This change means your body makes red blood cells that become C-shaped (sickled) and stick together. SCD can cause episodes of severe pain and lead to life-threatening complications. The most common and severe type of SCD is sickle cell anemia.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/12100-sickle-cell-disease)

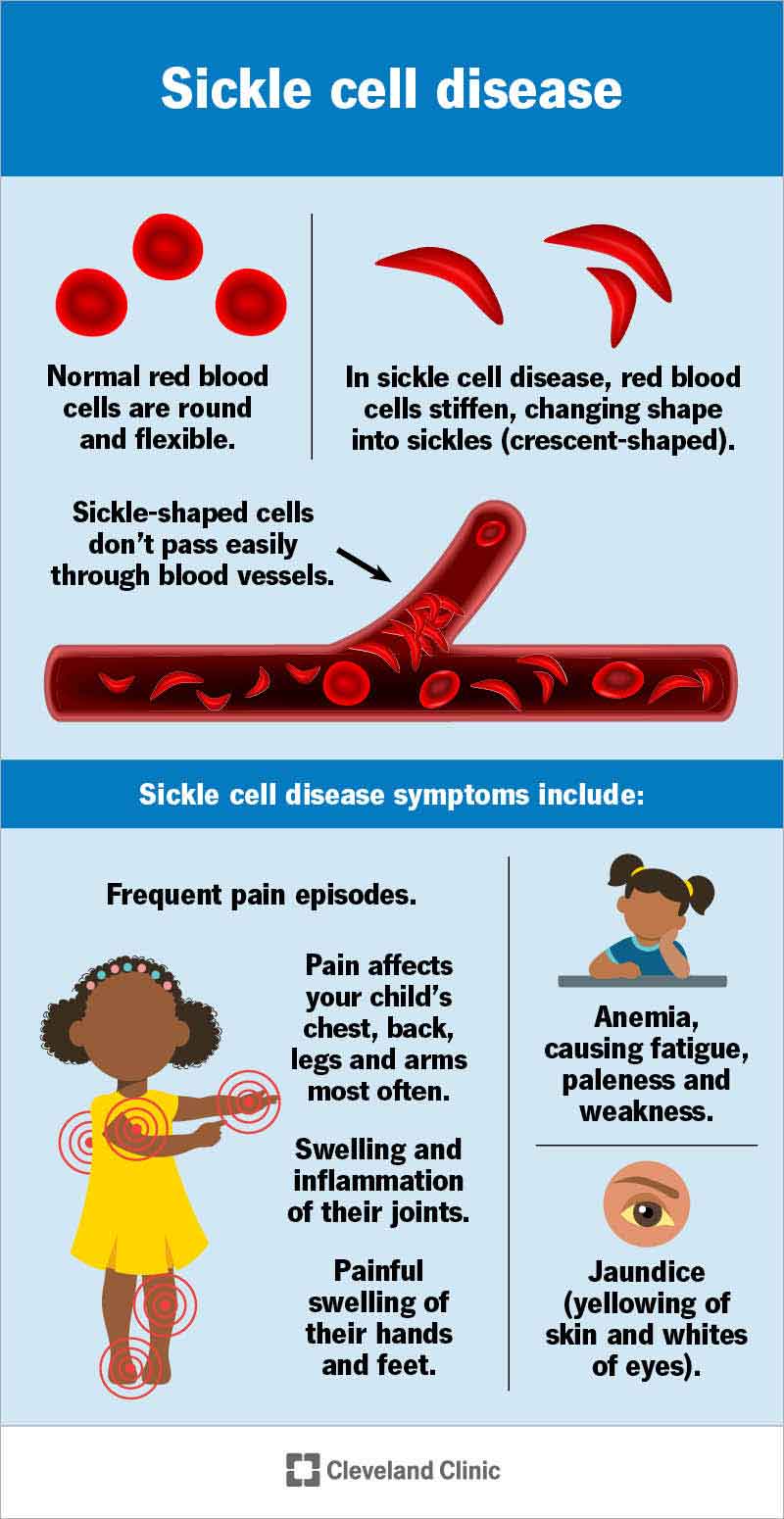

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic blood disorder. It causes your red blood cells to form into a “C” shape — like a crescent moon, or a farm tool called a sickle. These sickled blood cells can stick together and keep oxygen from getting to your tissues and organs. This can cause episodes of pain and life-threatening complications.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

You get sickle cell disease by inheriting two copies of a gene that makes a version of hemoglobin that doesn’t work properly. This causes sickling. Hemoglobin is the part of your blood that carries oxygen.

The symptoms and complications of sickle cell disease can start at any age. Babies can start having symptoms at 5 or 6 months old. Young kids can have frequent pain, anemia, blood clots and strokes.

Symptoms of sickle cell could include:

Signs and symptoms of SCD can be different for each person. They might be mild or severe.

A genetic variation in the HBB gene causes sickle cell disease. The HBB gene has the instructions for making hemoglobin, a part of your red blood cells that carries oxygen. Changes in this gene can make abnormal versions of hemoglobin, called hemoglobin S.

Normal red blood cells are donut-shaped. They’re flexible enough to move around the twists and turns of your blood vessels. This helps them bring oxygen to your organs and tissues. Red blood cells with hemoglobin S can become C-shaped and stick together. They can get stuck as they travel through your body. They also don’t last as long as normal red blood cells. All of this means your tissues and organs may not get enough oxygen to work properly.

Advertisement

Types of sickle cell disease include:

Both copies of your HBB gene have to have a variation for you to be diagnosed with SCD. If you have one hemoglobin S gene and one normal HBB gene, you have sickle cell trait. People with sickle cell trait often don’t have any symptoms of sickle cell disease. But you can pass the abnormal gene on to your children.

Many people think of sickle cell disease as autosomal recessive. This is because you usually have to have two abnormal copies of the HBB gene to have symptoms.

But sickle cell disease is actually an example of incomplete dominance or codominance. People with one abnormal HBB gene have both sickled and normal red blood cells. And, in certain circumstances, they can have symptoms of SCD.

You’re more likely to carry gene variants for sickle cell disease if you or your ancestors (parents, grandparents and other direct relatives) are from:

Pain is the most common complication of sickle cell disease. Blood cells can get stuck and block your blood flow. This prevents oxygen from getting to your tissues and can cause pain episodes called sickle cell crises, vaso-occlusive crises (VOC) or vaso-occlusive episodes (VOE). The pain might be temporary or last for several months. Sickle cell crises can come with other symptoms, like dizziness, fatigue, weakness or shortness of breath.

Other complications of SCD include:

Advertisement

If you’re pregnant and have sickle cell, you might be at higher risk for miscarriage, preeclampsia, having a baby with low birth weight and other pregnancy complications.

In many countries, including the U.S., hospitals test all babies for sickle cell disease. This is a heel prick (blood) test that’s part of routine newborn screenings.

Your healthcare provider can also diagnose sickle cell disease before your baby is born using prenatal testing. These tests include chorionic villus sampling and amniocentesis.

The only potential cure for sickle cell disease is a bone marrow transplant. This procedure replaces your bone marrow (where red blood cells are made) with a donor’s. But you have to find a donor who’s a good match (often a close family member, like a sibling). It’s also a risky procedure.

Treatments that help manage sickle cell disease include supportive care, disease-modifying agents and curative intent treatments.

Supportive care includes:

Disease-modifying agents include:

Advertisement

Curative intent options include:

During a crisis, you can try to manage the pain at home by taking pain relievers (ask your provider which they recommend), drinking plenty of fluids and applying heat to the area. If you can’t manage the pain at home, contact your provider or go to the emergency room.

Sickle cell disease can lead to life-threatening complications. Call 911 (or your local emergency services number) or go to the nearest emergency room if you or your child has:

Advertisement

If your child has sickle cell disease, they’ll probably go through good patches and bad ones. They might have frequent episodes of pain or fatigue, or need to miss school more often than other kids.

Not all kids have frequent symptoms. But you’ll need to know what serious symptoms to look out for and when to take them for emergency care.

There are many ways you can support your child:

Ways you can manage sickle cell disease include:

Studies suggest that people with sickle cell disease who haven’t had a stem cell transplant have a life expectancy of around 54 years. This estimate may not take into account new treatments that could be developed during your lifetime.

Since you’re born with sickle cell disease, there’s no way to prevent it. If you or your partner has sickle cell disease or sickle cell trait, you can talk to a genetic counselor about the possibility that your future children would have SCD.

If you have sickle cell disease, you have two abnormal copies of the HBB gene. You’ll have symptoms and are at risk for severe complications. If you have sickle cell trait, you only have one abnormal HBB gene. You probably won’t have symptoms or complications.

For most people, sickle cell is a lifelong condition. While it doesn’t define you as a person, it can have a huge impact on how you live your life — one that others may not always understand. Support groups and online resources can help connect you to others who know what life with sickle cell disease feels like. Understanding of sickle cell disease is growing. New treatments give hope that many more people can live healthier lives.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic cares for people of all ages with sickle cell disease. We walk you through your diagnosis and treatment and offer education and support services.