Only a few transplant centers in the world offer intestinal transplantation as a treatment option for intestinal failure and complications related to parenteral nutrition (PN). Cleveland Clinic's Pediatric Intestinal Rehabilitation Program and Nutrition Support Team provides patients with a unique opportunity to be evaluated, supported, and treated by a world class team of pediatric gastroenterologists, parenteral nutrition experts and transplant surgeons. The Transplant Center at Cleveland Clinic is recognized as one of the fewest and largest in the nation and offers the opportunity for heart, liver, kidney, pancreas, composite tissue (face) and intestinal transplantation. The expertise achieved in the transplant field since the “pioneer” years translates into today’s world class accomplishments and outcomes.

Cleveland Clinic is recognized in the U.S. and throughout the world for its expertise and care. For decades, Cleveland Clinic has offered alternative options to thousands of patients both nationally and internationally. The Pediatric Gastroenterology Department, recognized as one of the top Pediatric GI departments in the state of Ohio and the nation, offers patients a comprehensive “one-stop service” that includes diagnostic tools, nutrition support and surgical treatment whenever indicated.

Pediatric Intestinal Transplant Team

The Pediatric Intestinal Transplant Team at Cleveland Clinic is comprised of surgeons, physicians, coordinators, nurses, social workers and a vast network of people and resources to make the intestinal transplant process as smooth as possible.

Intestinal Transplant Center Leadership

- Program Director/Surgical Director, Intestinal Transplantation: Masato Fujiki, MD

- Medical Director, Pediatric Intestinal Transplantation: Kadakkal Radhakrishnan, MD

- Transplant Center Administrator: Liz Newhouse, RN, BSN, CCTC, CNOR, CCTN

Intestinal Transplant Surgeons

Intestinal Transplant Physicians

Clinical Nurse Manager

- Chris Moore, RN, BSN

Lead Transplant Coordinator/Assistant Nurse Manager

- Cindy Shovary, RN, BSN

- Erika Johnson, RD

- Debra Ficher, RN, BSN

- Danielle Dorobish, RN, BSN

- Neha Parekh, MS, RD, LD, CNSC

- Jessica Petry, RN

- Shatina Roddy, RN

- Anita Barnoski RN, MS

- Monu Goel, PA-C

- Amanda Pruchnicki, APRN

- Shannon Jarancik, PA-C

- Brittany McVan APRN

- Eric Wilhelm APRN

- Nicole Baitt, PA-C

Pediatric Intestinal Transplant Process

Learn about the intestinal transplant process

We know that learning about the intestinal transplant process and how to care for your child’s health may be overwhelming at first. But remember, you can learn a little each day. There will be times when you feel both excited and nervous about transplant: these are normal reactions. Being prepared in advance by learning and understanding what to expect will help ease your fear of the unknown. We have designed an extensive teaching program to help you learn about the intestinal transplant process, your child’s health needs, and medical care before and after your transplant. Always discuss your questions and expectations about intestinal transplant with your healthcare providers.

Be an active partner in your healthcare

We believe it is important for you, the parents, as well as your child to be active participants in the transplant process and work with the transplant team to promote a positive outcome. You will need to assume a lot of responsibility by doing whatever is necessary to build and maintain optimal growth and nutrition in preparation for intestinal transplant surgery. Your healthcare providers and dietitians are available to work with you to obtain this goal. Parents will learn how to recognize and report any change in the child’s condition. No one knows one's child better than the parents.

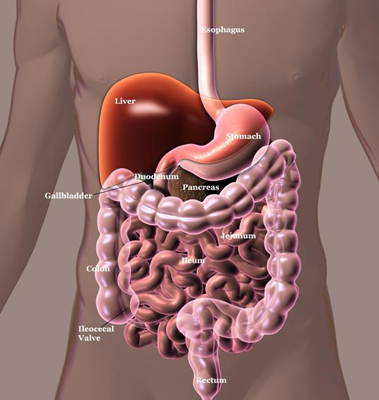

Your GI Tract

When you eat, your digestive system is responsible for turning food into the energy needed to survive. Digestion involves a series of physical and chemical processes in which food is broken down into nutrients and absorbed from the intestines into the blood stream. The digestive system extends from the mouth to the anus. Each section of the digestive system has a specific role in nutrient absorption.

Mouth

Digestion begins in the mouth. Chewing breaks the food into pieces that are more easily digested, while the digestive enzymes found in saliva mix with the food to start breaking it down into a form your body can absorb and use.

Esophagus

The esophagus, a hollow muscular tube, transports food from the mouth to the stomach through a series of muscular contractions called peristalsis.

Stomach

The stomach is an expandable, sack-like organ that holds food while it is being mixed with enzymes and strong acid that continues the process of breaking down food into a soft, semi-solid form. When the contents of the stomach are adequately processed, they are released into the small intestine.

Small Intestine

The small intestine is made up of three segments, the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum. A new born baby has between 6 to 8 feet (200 and 250 cm) of small bowel at birth. Most adult people have between 12 and 20 feet (365 to 600cm) of small intestine. Peristalsis moves food through the small intestine and mixes it with digestive secretions from the pancreas and liver. The duodenum is largely responsible for continuing the breakdown process, while the jejunum and ileum are mainly responsible for the absorption of nutrients into the bloodstream.

Enzymes released in the ileum help regulate the emptying of food from the stomach and the movement of food through the intestines. The last portion of the ileum is also responsible for the absorption of Vitamin B12 and unused bile salts. Once the majority of nutrients have been absorbed from the food; the leftover liquid (bile, enzymes, mucus, water, electrolytes, undigested fibers and waste) moves into the large intestine or colon.

Pancreas

The pancreas secretes digestive enzymes required for the digestion and absorption of carbohydrates, protein and fat. These secretions are released into the duodenum when food is present and helps break the food down into components which can be absorbed into the blood stream.

Liver

The main functions of the liver within the digestive system are to process nutrients absorbed from the blood stream and to produce and excrete bile salts. Once the liver has removed impurities from the blood, the nutrient-rich blood is delivered to the cells of the body. Bile salts are produced by the liver, stored in the gallbladder and secreted into the small intestine where they aid in the digestion and absorption of fats.

Colon (Large Intestine)

The colon, which is 2.5 feet at birth and 5-foot-long in adults, is a muscular tube that connects the small intestine to the rectum. It is made up of the cecum, the ascending (right) colon, the transverse (across) colon, the descending (left) colon, and the sigmoid colon, which connects to the rectum. Undigested material moves from the small intestine into the colon, where water and electrolytes, such as sodium and potassium, are absorbed. The rectum functions as a temporary storage site for the waste before it is passed from the body through the anus. Bacteria within the colon perform several useful functions such as making various vitamins, processing waste products and food particles, fermenting fibers into additional sources of energy, and protecting the body against harmful bacteria.

Indications for Pediatric Intestinal Transplant

Intestinal rehabilitation is the science that exhibits the amazing ability of the intestine to adapt to different and unexpected situations. It encompasses pharmacological, dietary, and surgical options that can reconstitute the intestine to normal function. Intestinal failure occurs when the intestine cannot sustain the nutritional needs of an individual and maintain adequate fluid balance. Parenteral nutrition (PN) is required in these cases in order to provide daily nutrition and hydration independent of the GI tract. Patients most likely to exhibit permanent intestinal failure or require long term parenteral nutrition include those with an inadequate remaining bowel length, an absent ileocecal valve and/or colon, active mucosal disease, bowel dysmotility, or infectious enteritis.

Bowel length and long-term PN requirement in SBS

When the intestine is irreversibly affected and rehabilitation is not possible, PN may be required indefinitely. Parenteral nutrition saves thousands of lives each year, but is not tolerated by everyone. Patients with a very short length of bowel, those who develop recurrent catheter related blood stream infections (CRBSI), or those who experience multiple central vein access thromboses may be at a higher risk of developing life threatening complications from the use of long-term parenteral nutrition. Indications for intestinal transplantation vary in the adult and pediatric populations.

In the pediatric population, intestinal failure is usually the result of one of the following:

- Short Bowel Syndrome (SBS): This is a malabsorption disorder caused by the surgical removal (resection) of large sections of intestine. Most cases are acquired due to removal of diseased bowel due to congenital malformation (gastroschisis, intestinal atresia) of the intestine, necrotizing enterocolitis (seen in some premature babies), or loss of blood supply to the gut (volvulus). The degree to which patients suffer the consequences of SBS depends largely on the remaining intestinal anatomy. For example, a large jejunal resection should not disturb absorption substantially because of the ability of the remaining ileum and colon to absorb increased fluid and electrolytes, maintain bile salts, and prolong movement of food and fluid through the intestine. A large ileal resection, on the other hand, leads to significant fat malabsorption, and if the colon also is resected, fluid and electrolyte balance can be severely impaired.

- Dysmotility disorders (may also be referred to as Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-obstruction (CIPO)): The anatomy and length of the bowel may be preserved, but the function (the way the small bowel moves) is impaired. Symptoms may be similar to a bowel obstruction and can include severe abdominal pain and distension, severe bloating, nausea, vomiting and the inability to eat.

- Intractable diarrhea of infancy: This includes conditions such as microvillus inclusion disease and tufted enteropathy. These conditions are associated with severe diarrhea where nutrition and growth can only be maintained by parenteral nutrition.

A list of the most common diagnoses preceding intestinal transplantation in the pediatric population is described below.

Pediatric diagnoses predicting intestinal transplant:

- Necrotizing enterocolitis.

- Gastroschisis.

- Omphalocele.

- Intestinal atresia.

- Volvulus.

- Intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

- Microvillus inclusion disease.

- Intractable diarrhea of infancy.

- Autoimmune enteritis.

- Intestinal polyposis.

Does your child need an intestinal transplant?

If your child’s medical condition falls into one of the following categories, he/she may be a candidate for an intestinal transplant.

- TPN Related Complications

- Parenteral nutrition-induced liver disease.

Liver failure is the worst complication induced by PN. An increase in bilirubin, ALT, AST and alkaline phosphatase may represent the first signs of liver failure. Liver failure is responsible for the majority of mortality caused by intestinal failure. We work really hard to avoid this complication. - Central venous catheter (CVC) related thrombosis of two or more central veins.

If you lose one or more central vein accesses from thrombosis of a PN line, you may be at risk of losing your remaining available access for nutrition and hydration (central veins). - Frequent episodes of central line sepsis.

This could include two or more episodes per year of systemic sepsis secondary to line infections requiring hospitalization or a single episode of line-related fungemia (infection caused by fungus). - Frequent episodes of severe dehydration despite intravenous fluid administration in addition to parenteral nutrition.

- Underlying Disease with an Increased Risk of Morbidity

- Congenital mucosal disorders (i.e. microvillus inclusion disease, tufting enteropathy).

- Ultra short bowel syndrome (gastrostomy, duodenostomy, residual small bowel <10 cm in infants and <40 cm in older children).

- Desmoid tumors associated with familial adenomatous polyposis.

- Intestinal Failure with an Intolerance to Parenteral Nutrition

- Intestinal failure with high morbidity (frequent hospitalizations, narcotic dependency) or inability to function (i.e. pseudo-obstruction, high output stoma).

Diagnosed with intestinal failure

If diagnosed with intestinal failure, the first step is to contact Cleveland Clinic's Pediatric Intestinal Rehabilitation and Transplant Center. Having a diagnosis of intestinal failure does not mean that you need an intestinal transplant. Only a small number of patients with intestinal failure progress to the point where transplant surgery is considered. You may be an excellent candidate for intestinal rehabilitation and adaptation.

Cleveland Clinic has one of the most successful pediatric intestinal rehabilitation programs in the world. There are essentially two ways of optimizing the intestinal function in patients with intestinal failure: medical/dietary treatment and surgical treatment. Medical/dietary treatment includes diet adjustments and medications that are prescribed to improve digestive and absorptive function of the remaining bowel (growth factors, drugs that increase or decrease the intestinal motility, etc.). A small number of patients are found to have out-of-circuit bowel as a result of previous surgery that can be put back in continuity with the bowel that is exposed to food so that absorptive function can be improved. Furthermore, new surgical procedures (STEP, Bianchi and tapering procedures) are offered at our center to enhance the residual intestinal function. If existing medical and surgical treatments do not improve intestinal function, intestinal transplantation becomes a consideration.

Types of Pediatric Intestinal Transplants

There are commonly three types of intestinal transplantation performed:

Isolated small bowel transplant

Isolated Small Bowel Transplantation (SBTx) typically includes the jejunum and the ileum. Occasionally, part of the colon may also be transplanted. Isolated SBTx is recommended when the cause of intestinal failure is primarily the small bowel. Successful SBTx may reverse PN–induced liver dysfunction.

Combined liver and small intestine

This type of transplant includes the liver, jejunum, and ileum (may also include the colon), and either part of or the entire pancreas. In this case, transplant is reserved for candidates with intestinal failure and irreversible liver failure induced by prolonged PN therapy. Medical presentations in these situations are more likely to include portal hypertension, severe fibrosis, or cirrhosis.

Multivisceral transplantation

Multivisceral transplantation usually includes stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum (colon may also be included), and pancreas. This procedure can be performed either including or excluding liver transplant. When the liver is spared, the native liver (the patient’s own liver) is preserved. This type of transplant is used to treat candidates with (1) locally, aggressive, non metastasizing abdominal tumors; (2) pseudo-obstruction and very poor gastric emptying; and (3) surgically unreconstructable gastrointestinal tracts (such as encountered in patients with multiple fistulas or congenital GI tract anomalies).

Discharge, Planning & Recovery

After your child leaves the hospital, he/she will still be recovering. For the first four to six months there will be some restrictions on daily activities. During the recovery period, the transplant team will closely follow your child’s progress. He/She will need to be monitored on a long term basis and you must agree to be available for blood work, examinations, abdominal scans, frequent endoscopic tests (see below), and frequent follow up appointments in the transplant clinic. As time after transplant passes, follow up visits tend to be less frequent unless complications develop. In this case, your child’s plan of care will be dependent on their medical condition. After transplant, the transplant team is committed to your child’s care and will follow him/her in the transplant clinic for life.

Outcomes and complications

Statistics from the Intestinal Transplant Registry show that one year after transplantation 83% of intestinal transplant patients are still alive and 70% are still alive at three years. The vast majority of these transplant recipients become free from parenteral nutrition. There are inherent risks in all surgeries, especially surgeries conducted under general anesthesia. Many complications are minor and get better on their own, but in some cases, the complications are serious enough to require another surgery or medical procedure. Immediately following transplant surgery your child will experience pain, but this will be carefully monitored and controlled throughout recovery.

Signs of rejection

The body's immune system protects against bacteria, viruses and fungi that can cause disease. White blood cells, which are part of the immune system, fight to rid the body of substances they recognize as foreign. The immune system will also identify a newly transplanted organ as being foreign and will, by nature, attack the transplanted organ. This process is called rejection. Rejection is common, especially during the first three months after a transplant and is diagnosed by having an intestine biopsy.

Such episodes are not uncommon and can usually be reversed with medicine, but only if detected early. Some of the signs and symptoms of rejection are identical to those associated with infection. This makes it extremely important to keep your clinic appointments and to notify the transplant coordinator of any symptoms so that the difference between rejection and infection can be determined. Your child may need to be admitted to the hospital for further diagnostic testing and treatment.

Rejection and infection are two serious problems that require completely different treatments. As with any health problem, the sooner treatment is initiated, the lower the chances are of serious illness developing.

Post operative rejection monitoring

The earlier a rejection episode is treated, the easier it is to treat and reverse. Therefore, it is important for you and your child to become familiar with possible signs and symptoms of rejection. Call your child’s doctor or transplant coordinator if you notice the following symptoms:

- Fever/malaise.

- Change in ostomy output (increased or decreased).

- Intestinal bleeding.

- Nausea/vomiting.

- Abdominal pain.

Whenever rejection is suspected based on clinical symptoms, an endoscopy is performed. This procedure is the only way to detect rejection and allows the macroscopic and microscopic appearance of the transplanted intestine to be analyzed under a microscope. The ileostomy (or colostomy) provides an easy opening to enter the intestine for the endoscopy.

Per protocol, endoscopies are performed at certain intervals, although this may change according to your child’s medical condition. In general, the first endoscopy and biopsy is performed via the ileostomy between postoperative days two and five. Ileoscopy and biopsy are repeated two to three times per week while in the hospital post transplant, weekly for the following three months, then monthly until stoma closure. Once the stoma is closed, endoscopies will be performed through the mouth or the rectum depending on which area of the intestine needs to be evaluated. In the case of rejection, endoscopies will be performed at least twice a week until resolution.

The endoscopy is a 10-15 minute procedure and is usually very well tolerated by the transplant recipient. A special scope called a zoom endoscope allows a close magnified evaluation of the transplanted bowel. Every endoscopy is accompanied by multiple intestinal biopsies (small pieces of mucosa) that are read by an expert transplant pathologist during the same day the procedure is performed. Because the transplanted intestine (also called a “graft”) is denervated, the procedure is painless. Some temporary gas distention may also be experienced.

Medication for life

Your child will be required to take medications for the rest of her/his life to prevent the body from rejecting the transplanted organs. The types and doses of medications will be determined and adjusted by the physicians based on your child’s condition and health. Following transplantation you and your child will receive further instructions and teaching regarding the medications specifically ordered. Listed below are examples of some, but not all, of these medications. It is important to note that all anti-rejection medications can increase the risk for infections and malignancies, so self-monitoring and health maintenance will be very important.

- Tacrolimus (Prograf): Usually used as a primary immunosuppressive agent.

- Cyclosporine (Neoral, Sandimmune): May also be used as a primary immunosuppressive agent.

- Sirolimus (Rapamune): Can be used as a primary or secondary agent.

- Mycophenolate mofetil (cellcept): May be used in addition to prograf as a secondary immunosuppressive agent.

- Steroids: Can be used to prevent and treat episodes of rejection. If used for rejection treatment, usually it is given by an IV.

The goal of various medications during and after transplantation is to help your child’s body tolerate the transplanted organs. Other medications may be required lifelong to treat or prevent various infections. The potential need for these medications may be determined by blood work obtained during the evaluation process.

Quality of Life (QOL) after intestinal transplantation

Based on quality-of-life studies performed in different transplant programs, most intestinal transplant recipients have a good or normal quality of life after transplantation. In a growing number of patients the quality of life is reported to be better than when they were on PN. As survival and quality of life continue to improve with experience, as it has dramatically happened in the past five years, intestinal transplantation may soon be offered to a wider population of PN dependent patients as standard of care therapy.

Major advancements have been made in recent years in immunosuppression, surgical techniques and post-operative care. Now, favorable outcomes for intestine transplants are no longer the exception; they are the expectation.

This means that most patients are able to resume normal lives after their transplant surgery. They no longer will need to rely on parenteral nutrition, but instead can enjoy eating again. Of course, patients will be followed for a lifetime by our medical team, and they will need to stay on a careful regimen of medications. Patients and their families learn about the signs and symptoms of rejection and infection, and they will become an active participant in their own care.

The time until return to normal daily activity is quite variable. Generally, patients need to wait at least six to 12 months before being allowed to return to school or work. If applicable, your child’s transplant team will help to decide the best timing.

Outpatient follow-up care

Signs and symptoms of problems such as rejection can be subtle and difficult to detect early. Delays in recognition of problems or diagnosis of problems can be life-threatening.

First Postoperative Months as Outpatient

All intestinal transplant recipients are required to remain in the Cleveland area for at least three months after discharge. Laboratory testing will be performed twice a week unless otherwise indicated and appointments will be scheduled at least once a week in the clinic. The transplant social worker or transplant coordinator are resources to discuss options for assistance regarding the cost of local housing.

First Postoperative Year

Clinic appointments usually occur every one to four weeks with laboratory testing on a weekly basis. All test results should be forwarded to The Intestinal Rehabilitation and Transplant Program at Cleveland Clinic. Many times it is possible for the recipients to be seen by their referring gastroenterologist on an alternating week basis with Cleveland Clinic visits (this is to be determined on an individual basis).

Beyond First Postoperative Year

Depending on the condition of the patient, visits are a minimum of four times a year. Laboratory testing is necessary on a weekly to monthly basis.