More than 30 strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV) can affect your genitals. These include harmless forms of HPV, like those that cause genital warts. Only some types of HPV are “high risk” because they can progress to cancer. You can take preventive measures, including the HPV vaccine and getting regular screenings, to reduce your risk.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/11901-hpv-human-papilloma-virus)

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a common virus that can affect different parts of your body. There are over 100 types of HPV, including strains of HPV that cause warts on your hands, feet and face. About 30 HPV strains can affect your genitals, including your vulva, vagina, cervix, penis and scrotum, as well as your rectum and anus. This includes the type of HPV that causes genital warts.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

HPV is the most common viral sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States. Roughly 14 million people get the infection each year. HPV is so common that most sexually active people who aren’t vaccinated against HPV will become infected at some point in their lives. Most never know they have it.

Some strains of HPV are high-risk and can lead to cancers, like cervical, vulvar and vaginal cancers. Early detection (with a Pap smear or HPV screening) and treatment of precancerous cells can usually prevent this from happening.

Certain strains of HPV (most often types 16 and 18) can cause changes in the cells of your cervix, a condition called cervical dysplasia. Left untreated, cervical dysplasia sometimes advances to cervical cancer.

If you’re under 30, most HPV infections clear up on their own. By age 30, finding HPV during a Pap smear can determine how often you should receive follow-up testing. If you test positive, you may be at a higher risk and need more frequent testing.

Getting regular Pap smears to screen for cervical cancer is important (usually beginning at age 21). But it’s important to remember that just because you have HPV or cervical dysplasia doesn’t mean you’ll get cancer.

Advertisement

The virus itself doesn’t turn into cancer. But high-risk strains of HPV infection can cause precancerous cell changes. These cell changes can eventually lead to cancer if they aren’t managed. This process, though, can take years or decades to happen. Screenings, like Pap smears, can help detect these precancerous cells before they turn to cancer.

HPV that affects your genitals doesn’t usually cause symptoms. When symptoms do occur, the most common sign of the virus is warts in your genital area. Genital warts are rough, cauliflower-like lumps that grow on your skin. They may also appear like skin tags. They may appear weeks, months or even years after you’ve been infected with low-risk HPV. Genital warts are contagious (like all forms of HPV). They can also be itchy and very uncomfortable.

High-risk forms of HPV often don’t cause symptoms until they’ve progressed to cancer.

Yes. And this can be confusing — especially when you’re trying to understand the difference between the HPV that causes the wart on your finger or genitals and the HPV that may lead to cervical cancer.

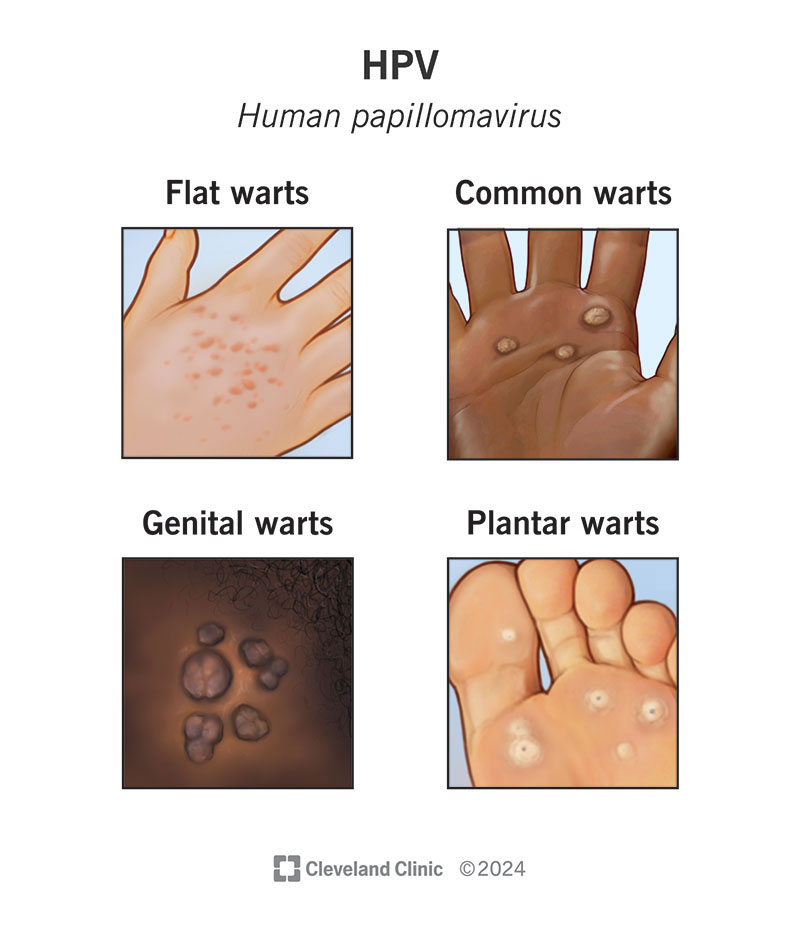

The HPV strains that cause warts, including genital warts, are nuisances. After all, no one wants warts, least of all on their genitals. Still, these types of HPV are harmless. HPV types 6 and 11 most often cause genital warts. Other types of HPV cause warts on other parts of your body. These warts are:

All warts are caused by HPV, but not all strains or types of HPV cause warts. The type of HPV that can progress to cancer doesn’t cause warts.

Genital HPV spreads through skin-to-skin contact during intercourse, oral sex and anal sex. You can get the infection if your genitals — including your vulva, vagina, penis and scrotum, as well as your rectum and anus — come into contact with these same body parts on an infected partner.

It’s possible to spread the virus through hand-to-genital contact, like fingering and handjobs. This type of transmission is less likely, and less is known about it than genital-to-genital contact.

HPV is highly contagious, in part because it’s transmitted through skin-to-skin contact. You don’t have to exchange body fluids with someone for you to contract the virus or spread it to someone else. You can infect your partner, or your partner can infect you even if no one ejaculates.

Anyone can become infected with HPV if they have sex or close skin-to-skin genital contact with a partner with the virus. Similarly, anyone with the virus can spread it to their partner during intercourse, oral sex, anal sex or other close genital contact.

Advertisement

If you have HIV, your immune system may have a harder time fighting HPV infections. Men who have sex with men may be at greater risk of contracting high-risk HPV strains that can progress to cancer. In this case, your provider may recommend an anal Pap test. Anal Pap tests don’t test for HPV, but they can test for cell changes that may lead to cancer. Ask your healthcare provider if you should get tested.

Regardless of your reproductive anatomy, it’s important to prevent the spread of HPV by getting vaccinated and by practicing safer sex (correct and consistent use of condoms or dental dams).

In general, HPV poses the greatest risk to females because high-risk HPV can progress to cervical cancer if it’s not treated. Pap smears and HPV tests can detect precancerous cell changes early to prevent cancer in your cervix. HPV can also cause genital warts in females.

HPV poses fewer health risks to males than females. HPV can cause genital warts in males, but most infections clear on their own. HPV can lead to cancers of your penis, anus, head and neck, but these cancers are rare. As a result, HPV tests and Pap tests aren’t generally recommended for males.

The most serious complication of HPV is cancer. Cervical cancer is the most common type of HPV-related cancer. Other types of cancer are much rarer. They include:

Advertisement

It’s important to remember that having HPV — even a high-risk strain — doesn’t mean that you’ll develop these cancers.

Genital warts are another complication of HPV. Genital warts can be itchy and uncomfortable and interfere with your daily life. Other than those symptoms, genital warts don’t cause much harm.

A healthcare provider will typically be able to diagnose genital warts and other bodily warts just by looking. High-risk forms of HPV don’t cause symptoms, which means you’ll likely learn about an infection through a routine Pap smear or HPV test.

Other procedures that can detect abnormal cells likely caused by an HPV infection include:

Advertisement

Treatments can’t rid your body of the virus. They can remove any visible warts on your genitals or other body parts, and abnormal cells in your cervix. Treatments may include:

Only a small number of people with high-risk HPV will develop abnormal cervical cells that require treatment to prevent the cells from becoming cancer.

The outlook for HPV is generally very good. It depends on what strain of HPV you have and how able your body is to fight off the infection. If you have a lower-risk strain of HPV and you’re in good health, chances are your body will clear the infection within 12 to 24 months.

Certain strains are more likely to lead to cancer. Your healthcare provider will monitor these strains and recommend further testing or treatment. Early detection of high-risk strains and follow-up screenings such as frequent Pap tests can prevent HPV from causing cervical cancer.

No. There isn’t a cure for HPV. Still, your immune system is incredibly efficient at getting rid of the virus for you. Most HPV infections (about 90%) are cleared within a year or two.

Not necessarily. You’re contagious for as long as you have the virus — regardless of whether or not you have symptoms. For example, even if your genital warts have disappeared, you can still spread the HPV that caused them if the virus is still in your body.

The only way to prevent HPV is to abstain from sex. For many people, more realistic goals include reducing the risk of contracting HPV and preventing cervical cancer while still enjoying a healthy sex life.

You can reduce your risk if you:

Contact your healthcare provider if you have any of the following:

You should also ask your healthcare provider about how frequently you should have tests that may indicate an HPV infection like Pap smears. Discuss any concerns you have about HPV with your healthcare provider, especially if you have a health condition that weakens your immune system. This can make it harder for your body to fight the virus.

It’s natural to have some questions about HPV. You may want to ask:

HPV is very common. Almost everyone has had or will have HPV at some point in their life. Most HPV infections clear up on their own because your body fights the virus.

It’s hard to say if your partner got HPV from you or someone else, as it can take years to show symptoms of HPV (if you show symptoms at all). The best thing you can do is be proactive about getting regular health screenings and then share your health history with your partner.

Learning you have human papillomavirus (HPV) can feel overwhelming and scary. You likely have many questions about what it indicates for your health or your sexual relationships. Before you panic, talk to your healthcare provider about the virus and what it means. Don’t assume you’ll get cancer. Not all forms of HPV are created equally. The HPV that causes genital warts may cause embarrassment, but the virus is harmless. Your body can clear most HPV infections. In those cases where your body can’t fight the infection, your provider can monitor cell changes for cancer. Talk to your healthcare provider about the HPV vaccine and get regular screenings.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Don’t ignore sexually transmitted infections. Cleveland Clinic experts will treat them confidentially and quickly in a judgment-free environment.