Cervical dysplasia is a precancerous condition. An HPV infection causes it. Without treatment, cervical dysplasia can lead to cervical cancer. Early detection and treatment can prevent these abnormal cells from becoming cancerous.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/15678-cervical-intraepithelial-neoplasia-cin)

Cervical dysplasia is a precancerous condition in which abnormal cells grow on the surface of your cervix. Your cervix is attached to the top of your vagina. It’s at the opening of your uterus.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Hearing the word “precancerous” can be scary. But most women with cervical dysplasia don’t develop cervical cancer. Receiving a cervical dysplasia diagnosis means that you might — not that you will — develop cervical cancer. Careful monitoring and treatments often prevent this. That’s why it’s important to see your gynecologist regularly for screenings.

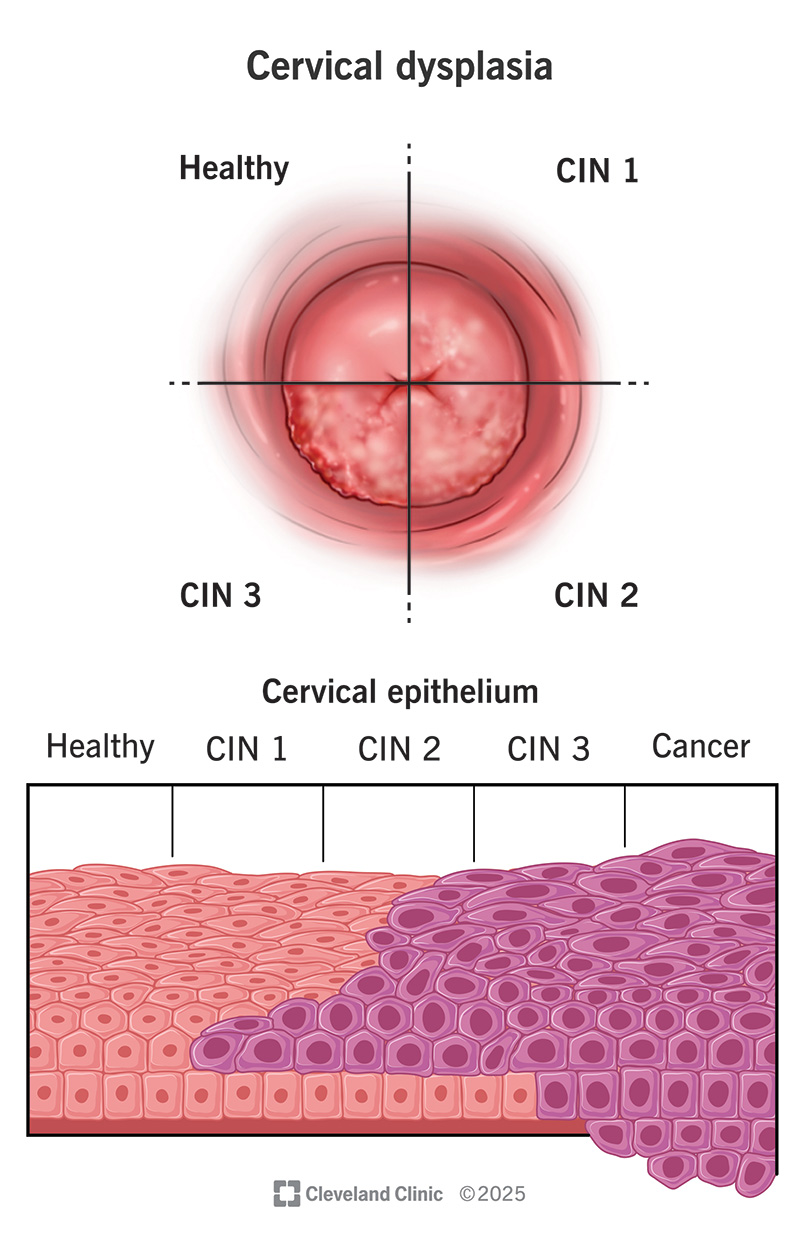

Another name for cervical dysplasia is cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). “Intraepithelial” means the abnormal cells are on the surface (epithelium) of your cervix. They haven’t grown past that surface layer. “Neoplasia” means abnormal cell growth.

Healthcare providers classify the severity of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) based on how much of the tissue looks abnormal under a microscope:

CIN 1 rarely becomes cancer and often goes away on its own. CIN 2 and 3 are more likely to require treatment to prevent cancer. About 100,000 women receive treatment for cervical dysplasia each year in the U.S.

Advertisement

Cervical dysplasia doesn’t usually cause symptoms. But some women may have irregular vaginal bleeding or spotting after intercourse.

Most women who have cervical dysplasia find out they have it after a routine Pap smear.

A virus called HPV (human papillomavirus) causes cervical dysplasia. HPV is the most common viral sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the U.S.

If you have cervical dysplasia, you have HPV. Some women have HPV but don’t develop cervical dysplasia.

Over 100 strains of HPV exist. In many cases, your immune system will get rid of the virus. But some strains, like HPV-16 and HPV-18, are more likely to cause cervical dysplasia.

Researchers don’t know why some women with HPV develop cervical dysplasia while others don’t.

Risk factors include:

The strain of HPV and how long you’ve had the untreated infection may also play roles in developing cervical dysplasia.

Your healthcare provider may notice signs of cervical dysplasia during a routine internal exam. They may do a test called a Pap smear. This is when your provider collects a sample of cervical cells that a pathologist can look at under a microscope. If the Pap smear reveals abnormal cells, you may need a:

Your healthcare provider will go over the results with you. Together, you’ll determine the next steps for treatment.

Treatment depends on various factors like:

Procedures to treat cervical dysplasia can impact pregnancy. Your healthcare provider will go over your options if you’re pregnant or plan to become pregnant.

With low-grade cervical dysplasia (CIN 1), you likely won’t need treatment. Most of these cases go away on their own. Only about 1% of CIN 1 cases eventually progress to cervical cancer.

Your healthcare provider may recommend periodic Pap smears to watch for any worsening changes in abnormal cells.

If the cervical dysplasia is more severe (CIN 2 or CIN 3), your provider may recommend removing or destroying the abnormal cells. These procedures cure cervical dysplasia in about 90% of all cases.

The procedures include:

Advertisement

Each of these procedures has risks and potential complications. You and your provider will discuss which option is best for you.

Your healthcare provider will want to check the health of your cervix over time. They’ll want to make sure abnormal cells don’t grow back or become cancerous.

Following treatment, they may recommend that you have a follow-up Pap smear every three to six months for one to two years. Afterward, you may resume having yearly Pap smears.

The outlook for cervical dysplasia with early diagnosis is excellent. Removing or destroying the abnormal cells significantly reduces your risk of cervical cancer. But these procedures come with certain side effects, like potential issues with pregnancy.

The only way to prevent cervical dysplasia is to avoid getting HPV. Prevention steps include:

Advertisement

Learning that you have precancerous cells on your cervix is stressful. But cervical dysplasia (CIN) doesn’t always lead to cancer. Early diagnosis and treatment can prevent cervical cancer from ever forming. Your healthcare provider will be by your side to answer any questions. Together, you’ll decide on a treatment plan that’s best for you.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Don’t ignore sexually transmitted infections. Cleveland Clinic experts will treat them confidentially and quickly in a judgment-free environment.