Pulmonic regurgitation is a condition where blood leaks back into your heart after being pumped out to your lungs. It's extremely common, and most cases involve very small leaks, which don't cause symptoms and aren't dangerous. Moderate or severe cases can damage your heart over time, causing serious or life-threatening problems.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/Images/org/health/articles/23280-pulmonic-regurgitation)

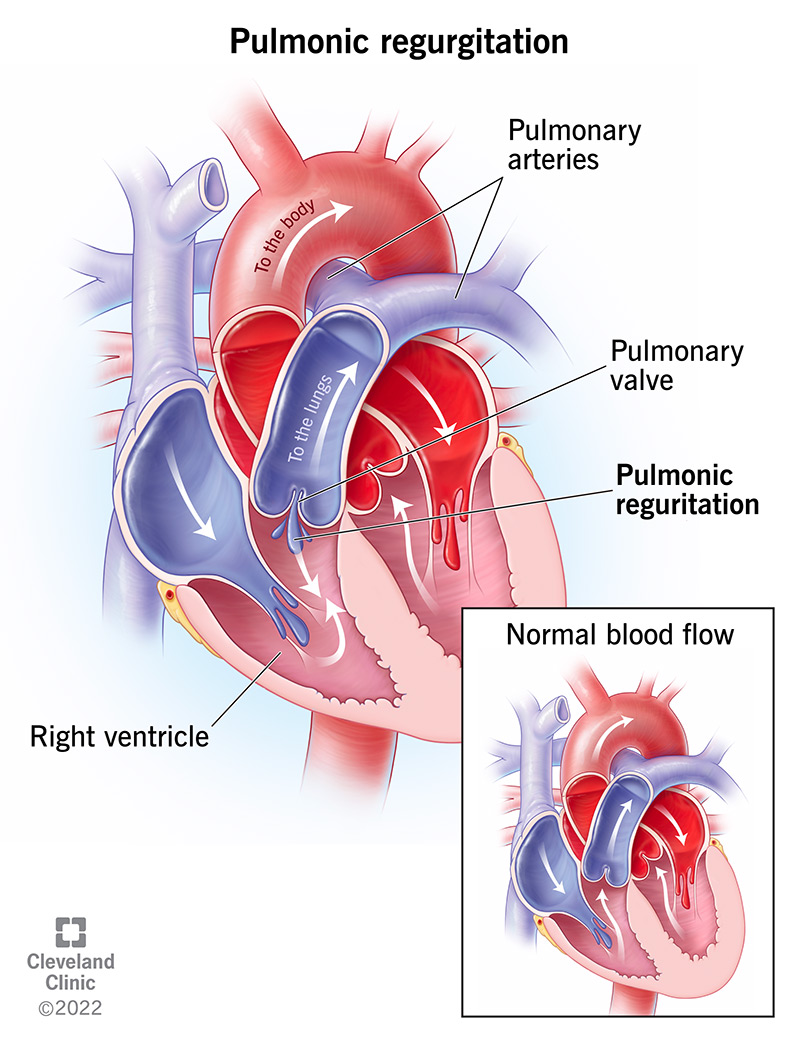

Pulmonic valve regurgitation is when the pulmonic valve in your heart doesn’t completely seal between heartbeats. That allows blood to leak the wrong way through the valve.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

When the leak is small, it usually doesn’t cause any problems. However, when pulmonic regurgitation is moderate or severe, that can damage the right ventricle and cause right-sided heart failure. Other names for this condition include pulmonic regurgitation, pulmonary valve regurgitation or pulmonary regurgitation.

Your heart has four chambers and four valves that manage blood flow through them. The pulmonic valve is the second valve that blood passes through in your heart, and it’s where blood exits the right ventricle. After passing through the pulmonic valve, blood goes through the pulmonary arteries to your lungs, where it picks up oxygen and drops off carbon dioxide.

When you have pulmonic regurgitation, not all of the blood pumped out of the right ventricle goes to your lungs. Some of it flows backward and reenters the right ventricle. That causes the right ventricle to pump harder, trying to compensate and force the extra blood out. Over time, that extra effort stretches and damages the right ventricle and causes right heart failure.

Pulmonic regurgitation is extremely common, happening to between 30% and 75% of the population (some sources suggest it’s even higher). However, the leak is almost always too small to cause any symptoms. Most people never know they have it unless they have a test that can detect it.

Advertisement

Moderate to severe pulmonic regurgitation can also happen for many reasons. Because there are so many potential causes, it’s hard to know how commonly the more severe forms of the disease happen.

The mildest forms of pulmonic regurgitation happen to people of all ages. The moderate and severe forms tend to happen at different stages of life:

Most people with pulmonic regurgitation have a leak that's too small to cause symptoms. Moderate or severe leaks are more likely to cause symptoms, many of which are similar to those seen with heart failure. These include:

When you have pulmonic regurgitation along with or because of another condition, you may also have other symptoms. Those symptoms depend on the other condition.

There are many potential causes of pulmonic regurgitation. Some of them include:

Advertisement

Pulmonic regurgitation isn’t contagious. However, it can happen because of contagious infections that spread to your heart or cause rheumatic heart disease.

Diagnosing pulmonic regurgitation can be tricky, depending on the severity of the problem and your symptoms. It usually involves a combination of a physical examination and diagnostic test imaging. A physical exam usually involves a healthcare provider doing the following:

Advertisement

The tests you’ll most likely have to diagnose this condition include:

In severe cases, your healthcare provider might request these tests:

Pulmonary regurgitation is usually treatable, and depending on the cause, it’s often possible to cure it. However, it usually doesn’t need treatment unless it’s severe, causes symptoms or both. When it’s severe but isn’t causing symptoms, the goal is to prevent it from getting even worse and causing permanent damage to the right side of the heart.

When pulmonary regurgitation happens because of another condition, the first step is usually treating or curing that condition. That often stops the regurgitation or at least reduces the size of the leak, so it causes fewer problems and symptoms.

If that’s not enough to stop the regurgitation, the goal changes to treating it directly. Treating and curing pulmonic regurgitation both involve replacing the valve itself. This can happen in two different ways:

Advertisement

Treating this condition also usually involves treating the symptoms causing you the most problems. These medications usually help your body get rid of excess fluid, improve circulation by relaxing blood vessels, or help control or prevent irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmias). Medications can also help your symptoms if you can’t have surgery for any reason, but they can’t cure this condition on their own.

If you have a replacement valve that isn’t biosynthetic, you might need to take blood-thinning medications for the rest of your life. These medications keep your blood from clotting around the valve. That helps prevent or reduce the risk of problems like stroke or pulmonary embolism.

Treating this condition with TPVR has a high success rate. About 94% to 98% of TPVR procedures are successful. Complications of TPVR are also rare, happening in 3% to 6% of cases (the most common complications are compression of the coronary artery or endocarditis from an infection).

Other possible side effects or complications from these treatments and procedures include:

Because this condition can look like so many other heart problems — some of which are life-threatening — you shouldn’t try to self-diagnose and treat it. If you suspect you have this problem, you should see a healthcare provider as soon as possible. They can determine if you have this condition and offer you treatment options.

The recovery time for this condition depends on the treatment method. Surgery isn’t the most common treatment, and it has the longest recovery time. People who have surgery for pulmonic regurgitation usually take weeks or months to recover. Recovery time for TPVR is much shorter, and you should start to feel better within a few days.

Most people with pulmonic regurgitation only have a mild or trace amount of leakage through the valve. For them, the outlook is good, and their lifespan should be the same as people without this condition.

Moderate leakage also usually has a good outlook with early treatment and diagnosis. This is especially true when there’s an underlying cause that’s curable or reversible.

With severe leakage, the outlook depends strongly on how long it takes for them to have it diagnosed and treated. In general, early diagnosis and treatment increase your chances of curing this condition or at least treating it so you can minimize its effects. Your healthcare provider can tell you what your outlook is and what you can do to improve that outlook.

Pulmonary regurgitation is usually a life-long condition unless cured with treatment.

Most people who have TPVR only need to stay in the hospital for four or five days, and most can return to work immediately after that. If you have surgery for TPVR, recovery and return to your routine can take weeks or even months. Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you when you can return to work, school or your regular routine.

Pulmonic regurgitation isn’t fatal on its own. Instead, it causes other conditions that become life-threatening over time. That’s why early diagnosis and treatment are so important.

Because pulmonic regurgitation happens unpredictably, preventing it is impossible. This is especially true when it happens because of conditions you had when you were born. All you can do is reduce your risk by avoiding situations or conditions that might cause you to develop it.

The only way to reduce your risk of developing pulmonic regurgitation is to avoid infections that can cause it. That means getting any infection, especially ones like strep throat, treated as soon as possible. That prevents the infection from turning into rheumatic heart disease or spreading to and damaging your heart directly.

Your healthcare provider is the best person to tell you what you can and should do to manage your symptoms and care for yourself. In general, you should do the following:

If your symptoms return or change unexpectedly, you should call your healthcare provider. This is especially true when changes happen suddenly or when symptoms start to interfere with your regular routine and activities.

You should go to the hospital if you have any of the following symptoms, which can also happen with heart failure, heart attacks or other dangerous heart problems:

Pulmonic regurgitation is a common condition, and for most people, it's not a cause for concern. It can cause symptoms that disrupt your life when it is more severe. If not treated, it can also ultimately lead to serious and even deadly complications. Fortunately, this condition is often treatable — or even curable — and the most common treatment procedures have very high success rates.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Pulmonary valve disease may come as a shock. At Cleveland Clinic, you’re in the most capable hands. We’re ready to help you journey to a healthy heart.