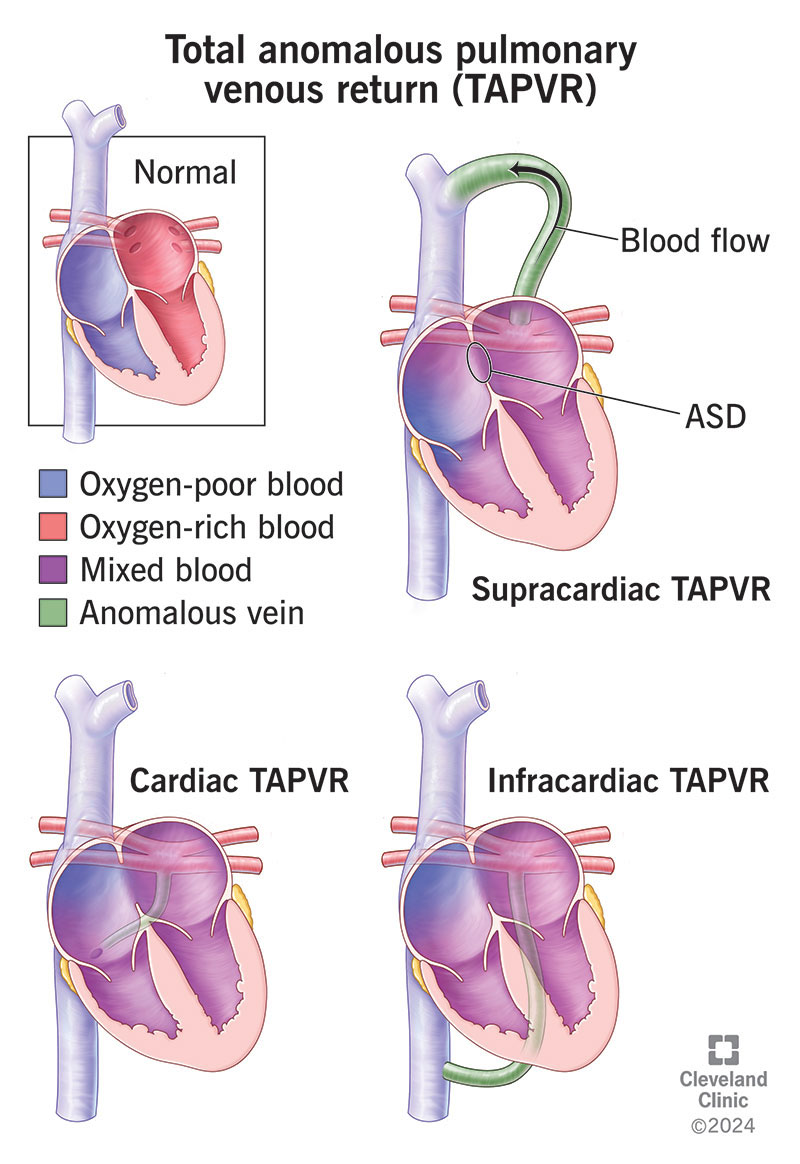

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR) is an issue where veins from your baby’s lungs connect to the right side of their heart instead of the left. Blood with and without oxygen mixes, which keeps their body from getting enough oxygen. This is a rare, life-threatening congenital heart issue that affects newborns.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/23069-total-anomalous-pulmonary-venous-return-illustration)

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR) happens when veins that bring blood from your baby’s lungs connect to the wrong place in their heart. As a result, their heart can’t put enough oxygen into the blood it sends to the rest of their body. TAPVR is a life-threatening heart condition. It’s congenital, which means it’s present at birth.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Typically, your lungs send oxygen-rich blood to your heart’s left atrium (the chamber in your heart’s upper left side). In babies with TAPVR, the oxygen-rich blood flows through pulmonary veins to their heart’s right atrium instead.

In the right atrium, the oxygen-rich blood mixes with blood that doesn’t have as much oxygen. This low-oxygen blood travels out of the heart to the rest of your baby’s body.

Babies with total anomalous pulmonary venous return may have trouble breathing soon after birth. Their skin may appear blue (or gray on darker skin).

All children with TAPVR also have an atrial septal defect. This is a hole between the heart’s right and left atria.

Total anomalous pulmonary venous return is a rare condition. It affects 1 in about 7,800 newborns in the U.S. each year. You may hear a provider call this condition total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC).

TAPVR types differ by how blood reaches the wrong place — your baby’s right atrium.

The TAPVR types are:

Advertisement

Symptoms of total anomalous pulmonary venous return may include:

Symptoms of TAPVR usually appear very soon after birth. Babies have symptoms at birth if they have any narrowing where their lung veins connect to their hearts. But some babies don’t have symptoms for several weeks.

Healthcare providers aren’t sure what causes total anomalous pulmonary venous return. It happens when your baby’s heart and blood vessels are forming in the uterus during fetal development.

This doesn’t seem to be an inherited condition (passed down through families). But there have been similar cases among siblings. TAPVR has an association with certain syndromes and exposure to paint removers, pesticides and lead.

A baby with TAPVR can have heart failure and pulmonary hypertension. Even after the initial repair, TAPVR can sometimes lead to abnormal heart rhythms or blockages in your child’s pulmonary veins.

Children with TAPVR may have trouble with typical development, like fine motor function. You can help your child by getting screenings for developmental milestones. If a screening shows a developmental delay, you can arrange for someone to work with them to improve their skills.

Talk to your child’s healthcare provider about their ability to take part in sports and physical activities. Your child may need to limit vigorous exercise.

Cardiologists can sometimes diagnose this condition with an echocardiogram before birth. Some babies don’t get a diagnosis until they’re several weeks or months old.

After your baby is born, their provider will do a physical exam and listen to your baby’s heart. A pulse oximeter (pulse ox) can measure the amount of oxygen in your baby’s blood. It fits over your baby’s big toe and sends information through a wire.

To diagnose total anomalous pulmonary venous return, a provider may use:

Some of these tests (MRI) may require anesthesia, but they’re all noninvasive. They allow your baby’s healthcare provider to see images of your baby’s heart and veins. They also help them evaluate blood flow and look for abnormalities.

A provider can use cardiac catheterization to make a diagnosis. But they can usually get the information they need from imaging. This spares your baby from an invasive procedure.

Healthcare providers treat TAPVR with open-heart surgery. Most often, providers perform this TAPVR repair as soon as they can after diagnosing the condition. Nearly every baby with total anomalous pulmonary venous return needs surgery to survive.

Advertisement

Though it’s extremely rare, some people don’t have surgery as babies and get a TAPVR diagnosis as adults. But they usually have high pressures within their lungs (pulmonary hypertension). This can make surgical repair very challenging.

While waiting for surgery, your child may receive extra oxygen or a ventilator to help them breathe. They may receive an inotrope, which is a medicine that helps their heart beat more forcefully.

While your baby is asleep under general anesthesia, a surgeon:

After TAPVR surgery, your baby will have checkups every six to 12 months. They’ll need regular follow-up visits through adulthood. Your child’s provider may want to order tests like an electrocardiogram, exercise stress test or echocardiogram.

Get medical help right away if your baby:

Questions to consider asking your child’s healthcare provider may include:

Advertisement

Babies who have TAPVR need an operation. With early surgery, most children with TAPVR survive into adulthood. But some will need repeat surgery or procedures to treat narrowing in their veins later in life. Because of this, people with TAPVR need to see a cardiologist (a heart expert) regularly to monitor their health following surgery.

Without surgery, some forms of total anomalous pulmonary venous return are typically fatal a few weeks after birth. With early diagnosis and surgical treatment, the outlook for babies with TAPVR is very good. The survival rate after surgery is around 97%.

Your child will need regular visits with their cardiologist as they grow into adulthood. Lifelong follow-up visits can help cardiologists find problems like an irregular heartbeat or blockages (obstructions) in their blood vessels. An obstruction requires another surgery and may be hard to treat.

Your child may need to take medicine or have a procedure like a cardiac catheterization.

There’s nothing you could’ve done to prevent this congenital heart condition. But if you’re thinking of starting a family and have TAPVR or a family history of congenital heart conditions, you might want to speak with a healthcare provider.

Advertisement

You’ve carefully followed your provider’s instructions for a healthy pregnancy. But somehow, your newborn has a heart issue. Today’s medical advances give your baby a better outlook than previous generations. Surgical treatments for TAPVR are extremely effective. The outlook for people with this condition is very good. Following surgery, be sure to take your child to see their healthcare provider for regular follow-up visits. These visits help your child’s provider treat problems and monitor their health.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

When your child is diagnosed with total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR), Cleveland Clinic Children’s can provide personalized treatment.