A tonic-clonic seizure causes sudden muscle stiffness, shaking and loss of consciousness. It happens when abnormal electrical activity spreads through your brain. It can affect people of any age. It may be linked to underlying conditions or different triggers. Many treatment options are available to help manage these seizures.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Tonic-clonic seizures, formerly known as grand mal seizures, cause stiff muscles, involuntary jerking movements and a loss of consciousness. Abnormal electrical activity in your brain causes them.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

It involves passing out and shaking uncontrollably. It can be scary to witness, and even more uncomfortable to experience. This is because you’re at high risk of injury when you fall. And afterward, you may feel confused or disoriented when you wake up.

These events are often unpredictable, but a healthcare provider can help you manage them and stay safe.

There are two types based on the location in your brain:

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/tonic-clonic-seizure)

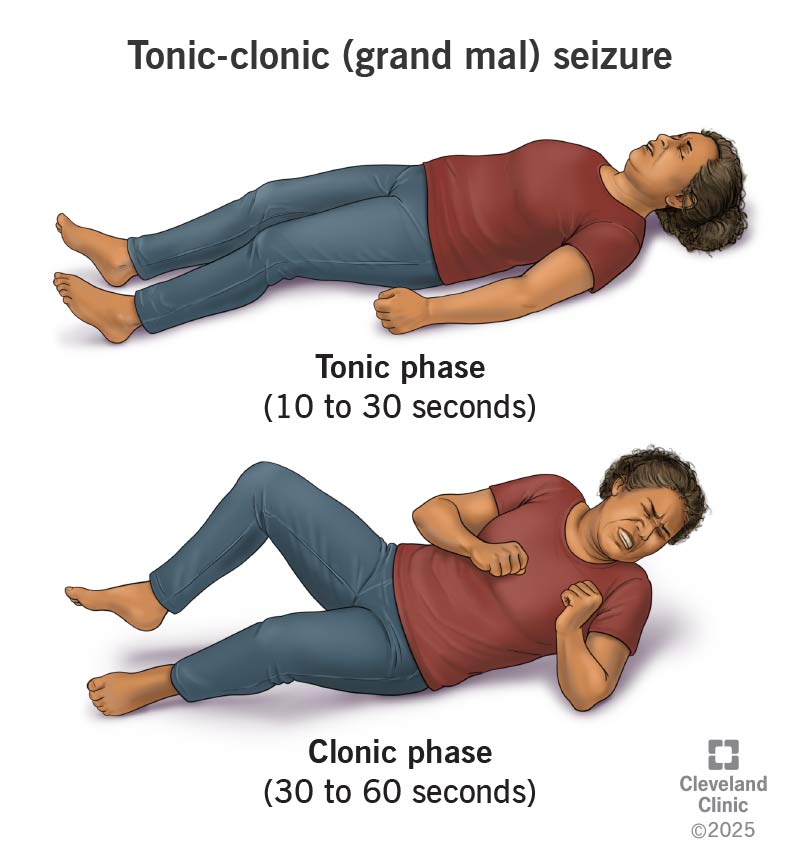

When most people picture a seizure, a tonic-clonic seizure is likely the one they think about. Symptoms are easier to spot and happen in the following phases:

You may bite your cheek or tongue during the seizure. This could cause bloody saliva. Fall injuries are also common as you lose consciousness.

Advertisement

When it’s over, you may wake up with:

A surge of electrical activity in your brain causes a tonic-clonic seizure. The reason why this happens is unknown.

Normally, brain cells (neurons) use electrical and chemical signals to send messages. But during a seizure, the signals go out of control and spread too fast. This sudden burst of activity leads to symptoms.

Tonic-clonic seizures may be a symptom of epilepsy. Epilepsy means you have unprovoked seizures often. You may have seizures with or without an epilepsy diagnosis.

Several conditions have also been known to cause tonic-clonic seizures:

Complications may include:

A seizure that lasts over five minutes (status epilepticus) is an emergency. Without quick treatment, it can cause brain damage or even death.

A healthcare provider will make a diagnosis after a physical exam and a review of your symptoms. Because you passed out, you may not remember what happened. Your provider may ask someone who was with you to describe what they saw.

Testing may confirm a diagnosis or rule out conditions with similar symptoms. These may include:

These tests can also help your provider determine the best treatment option to manage symptoms.

Most seizures stop on their own within minutes. To prevent choking, you can roll the person onto their side. This helps them keep breathing. Call emergency services if it lasts longer than five minutes.

To manage tonic-clonic seizures long term, a healthcare provider may recommend:

If seizures don’t respond to medical management, an epilepsy specialist may assess you to see if you’re a candidate for:

Advertisement

Common anti-seizure medications may include:

Each medication comes with possible side effects. Your provider will discuss these with you so you know what to expect.

If you’re undergoing treatment, you’ll have regular check-ins with your provider to see how well it’s working. They may run tests to monitor your brain activity periodically. Be sure to tell them about any side effects you experience.

If you have a seizure for the first time, contact 911 or your local emergency services number.

After the first seizure, you’re more likely to have another. But sometimes, it can be a one-off (where you only have one and no more after that). Your provider can help treat any underlying conditions that may be triggering symptoms or recommend options to manage the seizures themselves. This may reduce how often they happen or how severe they are.

Your provider can also suggest ways to make your home safer, like padding sharp corners or using non-slip rugs. You can wear a medical ID bracelet, too, to inform others if you have an unexpected seizure. Providers can connect you with support if complications arise.

Advertisement

Tonic-clonic seizures are tough on everyone involved — they’re scary, sudden and hard to predict. While they may feel chaotic, especially the first time, most only last a few minutes.

Treatment may not stop seizures completely, but for many people, it can reduce how often they happen or how disruptive they are. If you or a loved one is navigating seizures, know that there are options to help you stay safer and feel more in control. Don’t hesitate to reach out to your care team with questions.

Advertisement

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Epilepsy and seizures can impact your life in challenging ways. Cleveland Clinic experts can help you manage them and find relief.