Distributive shock or vasodilatory shock is the type of shock healthcare providers see most often. Septic shock from sepsis makes up the largest number of cases, but people also get distributive shock from severe allergic reactions or asthma attacks. Quick treatment is very important, as it gives you the best odds of survival.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22762-distributive-shock)

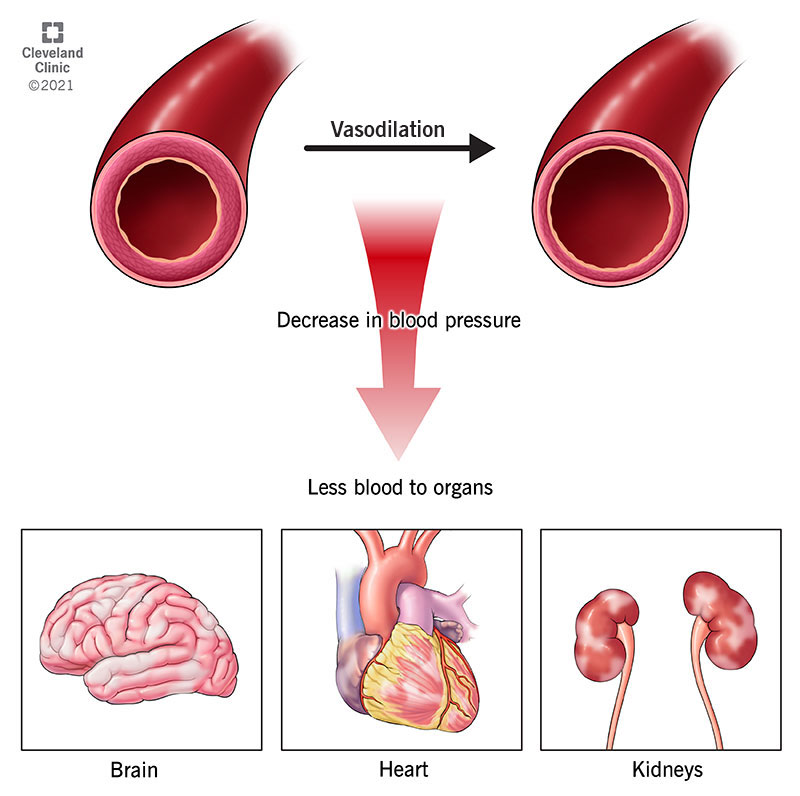

Distributive shock or vasodilatory shock is a medical emergency where your body can’t get enough blood to your heart, brain and kidneys. This happens because your blood vessels are extremely dilated (flaccid or relaxed), which brings down your blood pressure and cuts down on how much blood can get to your organs. Often the small blood vessels (capillaries) are leaky in distributive shock, resulting in some fluid loss from the circulation.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

You need to get treatment as soon as possible for vasodilatory shock.

Both of these are types of shock, which means your vital organs aren’t getting enough blood and oxygen. The difference is in what causes them. Most often, an infection complication called sepsis or a severe allergic reaction causes distributive shock. A large amount of bleeding or fluid loss from diarrhea or throwing up causes hypovolemic shock.

Septic shock is a type of distributive shock. When you have an infection called sepsis, it can get so bad that it turns into septic shock.

Distributive shock is the most common of the four types of shock, with the others being hypovolemic, cardiogenic and obstructive shock. Each year, 1 million Americans get septic shock, which is the top cause of distributive shock. It can affect anyone.

Advertisement

Because of unusually flaccid blood vessels, distributive shock lowers the pressure driving blood flow to your organs and prevents your organs from receiving enough blood to do their jobs. This lack of oxygen and nutrients can make your organs stop working correctly. When your organs fail, it can be fatal.

Distributive shock signs and symptoms may vary depending on the cause. Symptoms include:

Distributive shock causes include:

Your provider will want a physical exam and medical history. Often, someone in shock may not be able to speak for themselves. A loved one can tell your provider if you have an allergy or have had anaphylaxis in the past. Knowing what medicines or drugs you’re taking will help your provider with a diagnosis, as well.

Your healthcare provider will order the following tests, some of which may be able to be brought to your bedside:

Your healthcare provider will give you IV fluids, like saline. Next, they will give you medicines to address the cause of your vasodilatory shock. Then, they may give you some nourishment (probably through a tube feeding).

You’ll be in the intensive care unit (ICU) after most likely starting out in the emergency room. Your provider will continue to check your vital signs and watch for side effects of your treatment. You may need a ventilator to help you breathe if you’re having trouble breathing on your own.

Depending on the cause of your distributive shock, your provider will give you the following medicines:

Side effects from vasopressors include:

Advertisement

Antibiotics can cause nausea and diarrhea. Albuterol can make you feel nervous, dizzy or sick to your stomach. Antihistamines can make you sleepy or dizzy. They can also give you a headache or fast heart rate.

If sepsis caused your vasodilatory shock, you may have long-term problems, such as feeling tired, having nightmares or not wanting to eat. No matter what caused your distributive shock, you’ll need to keep going to follow-up appointments with your provider. You’ll also need to keep taking any medicines your provider prescribed for you.

Depending on how sick you are, you may be in the hospital for a few days or weeks as your body recovers from distributive shock.

Depending on the cause, the likelihood of dying from distributive shock is 20% to 80%. Without treatment, shock is often fatal. A quick diagnosis and treatment give you the best chance of survival. Older adults and those who drink alcohol have worse odds, as do people who have problems with more than one organ.

If your body responds well to fluids and your organs are able to keep working, you’ll likely have a good outlook.

Although you may not be able to avoid some causes of distributive shock, such as infections or burns, you can cut down your risk of shock from known problems in these ways:

Advertisement

After you go home from the hospital, follow your provider’s instructions for caring for yourself. You might have to rest at home for a few days or weeks to feel well enough to go back to work. Keep going to any follow-up appointments and keep taking your prescription medicines.

Contact your provider if you start feeling worse when you’re recovering at home.

Anyone with signs of distributive shock should go to the emergency department. While waiting for paramedics to arrive, you should make sure the person with shock is lying down. Put a blanket on them to keep them warm and raise their legs up about a foot from the ground to improve their circulation.

Advertisement

Distributive shock is a medical emergency that you need to be treated for right away. Getting help quickly is crucial and improves your chances of survival. Be patient with yourself; recovery takes time. While you’re recovering at home, make sure you take the medicines your provider ordered and go to any follow-up appointments.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.