Locked-in syndrome (LiS) is a rare and serious neurological disorder that happens when a part of your brainstem is damaged, usually from a stroke. People with LiS have total paralysis but still have consciousness and their normal cognitive abilities. Most people with LiS can communicate with eye movements and lead meaningful lives.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

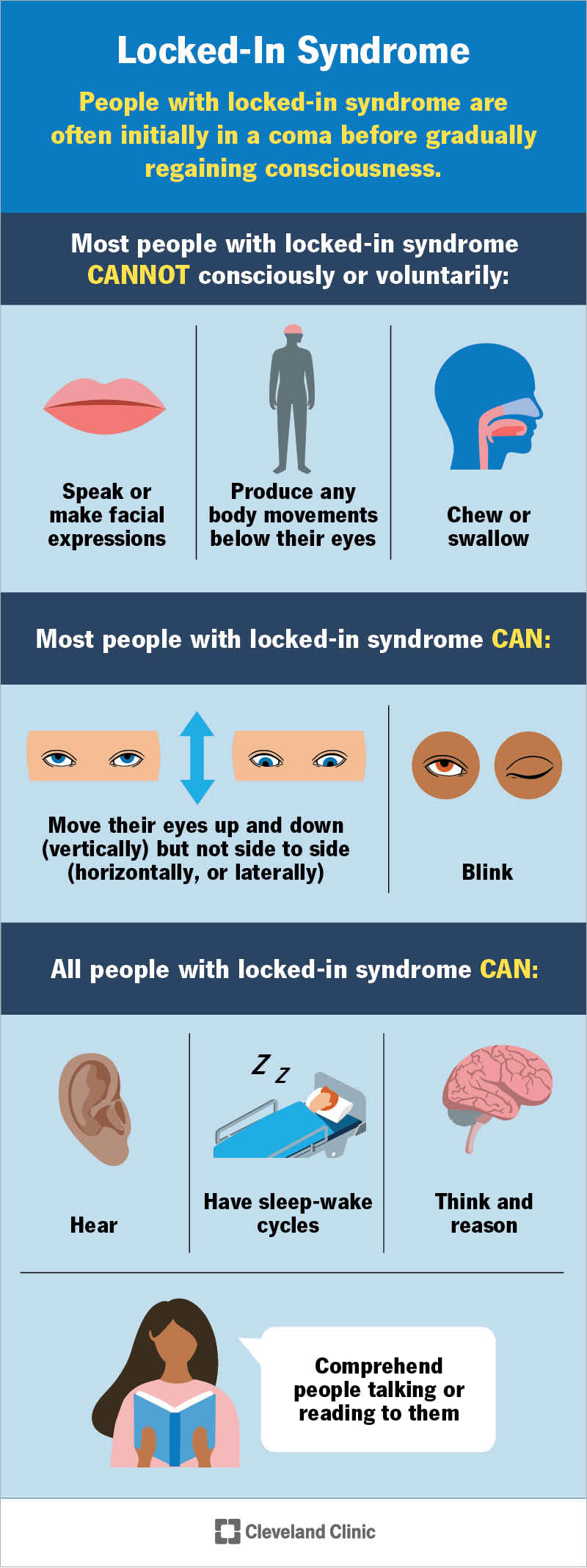

Locked-in syndrome (LiS) is a rare neurological disorder that causes paralysis of voluntary muscles, except for those that allow you to move your eyes up and down. People with locked-in syndrome are conscious, alert and have their usual thinking and reasoning abilities. But they can’t show facial expressions, talk or move.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

People with LiS can hear and typically communicate through purposeful eye movements, blinking or both. They can also use assistive technologies to communicate.

Damage to a specific part of your brainstem, known as the pons, causes this syndrome.

Anyone can develop LiS. It’s usually the result of underlying disease, such as stroke or a brain tumor. Because LiS may go unrecognized or misdiagnosed, it’s hard for researchers to know the actual number of cases each year. But they agree that it’s rare.

Locked-in syndrome has three main types, or forms, including:

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/22462-locked-in-syndrome)

The effects of locked-in syndrome on your body vary slightly depending on which type you have. Healthcare providers often first think people with this syndrome are in a coma before they test for consciousness.

Advertisement

Most people with locked-in syndrome cannot:

Most people with LiS can:

All people with locked-in syndrome can:

Depending on which form of LiS you have, you may or may not feel physical pain. If you have the total immobility form, you won’t feel pain due to total paralysis. If you have the incomplete form, you may feel pain and other sensations in certain areas of your body.

Damage to a specific part of your brainstem called the pons causes locked-in syndrome.

Several specific conditions and situations can damage your pons, causing locked-in syndrome. The most common cause is stroke affecting certain motor tracts in your brainstem, such as the corticospinal, corticopontine or corticobulbar tracts..

Other less common causes of damage to your pons that can lead to LiS include:

Most cases of locked-in syndrome aren’t preventable. But your risk of it may increase if you have stroke risk factors, like high blood pressure.

With LiS, you generally retain your mental abilities. But some people with LiS develop issues with:

Locked-in syndrome can lead to death. This is more likely to happen when the symptoms first appear (the acute phase). Death is also more likely when a major stroke is the underlying cause. This often also suppresses your breathing responses.

Locked-in syndrome can be difficult to diagnose or take a while to diagnose correctly. A large part of getting a diagnosis is ruling out other conditions that have similar symptoms. Providers also need to find the cause of the syndrome.

Tests providers use include:

Advertisement

There’s no cure or specific treatment for locked-in syndrome other than treating the cause and preventing further complications.

Management includes supportive therapy and communication training. Intensive rehabilitation may help you recover some movement function.

Supportive therapy for breathing and feeding is very important, especially early on. You’ll likely need an artificial aid for breathing and a tracheostomy (a tube going in your airway through a small hole in your throat).

Eating and drinking using your mouth isn’t safe with LiS. So, you may have a small tube inserted in your stomach called a gastrostomy tube to get food and water.

Other supportive therapies include:

Speech therapists can help you communicate more clearly with eye movements and blinking. The method of communication is unique to each person.

For example, looking up could mean “yes” and looking down could mean “no” or vice versa. You may also form words and sentences by signaling different letters in the alphabet as someone lists each letter.

Advertisement

Electronic communication devices, like infrared eye movement sensors and computer voice prosthetics, may also help you communicate more freely and use the internet.

New communication technologies, like brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), are constantly emerging. Keep in contact with your healthcare team to learn about what’s available.

Each case is different. A substantial recovery of movement is possible and can continue over the years. For example, you may be able to move your head or arm eventually. But it’s highly unlikely that you’ll return to how your body moved before LiS.

According to one study, the likelihood of recovery is better in those who have a nonvascular cause of LiS (like a tumor or infection) compared to vascular causes (like a stroke).

Quick diagnosis and treatment can help increase your odds of recovery. Starting rehabilitation as soon as possible is also key.

The prognosis (outlook) for people with locked-in syndrome depends on the cause and form of the condition. The level of support and care you receive also matters. Your healthcare team will be your guide throughout your recovery. You’ll likely need years of rehabilitation.

Studies show that people with LiS report having a meaningful life. Especially when they have proper access to services and technology to help them at home and in their community.

Advertisement

Many people with LiS can use a motorized wheelchair and a computer with adaptive technology.

It’s impossible to predict life expectancy because each case is different. Some people with locked-in syndrome don’t live beyond the early stage of the condition due to complications. But others may live for another 10 to 20 years.

Locked-in syndrome (LiS) is a rare but serious condition. It can be very overwhelming and isolating to receive this diagnosis. Know that your healthcare team is there to support you and your loved ones. It’s key to get continuous quality care when living with LiS and learn new ways of communicating. Due to supportive care and advancements in technology, many people with LiS live full and meaningful lives.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

After a stroke, it’s essential to get treated right away. Cleveland Clinic’s stroke care specialists can help you manage recovery and improve your quality of life.