Progeria is a rare genetic condition that causes rapid aging in children. A tiny genetic mutation causes the disease. Progeria causes signs of aging such as balding and wrinkled skin. The condition is always fatal. Death most often occurs as a result of heart attack or stroke. A drug called lonafarnib may slow down the progression of the disease.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

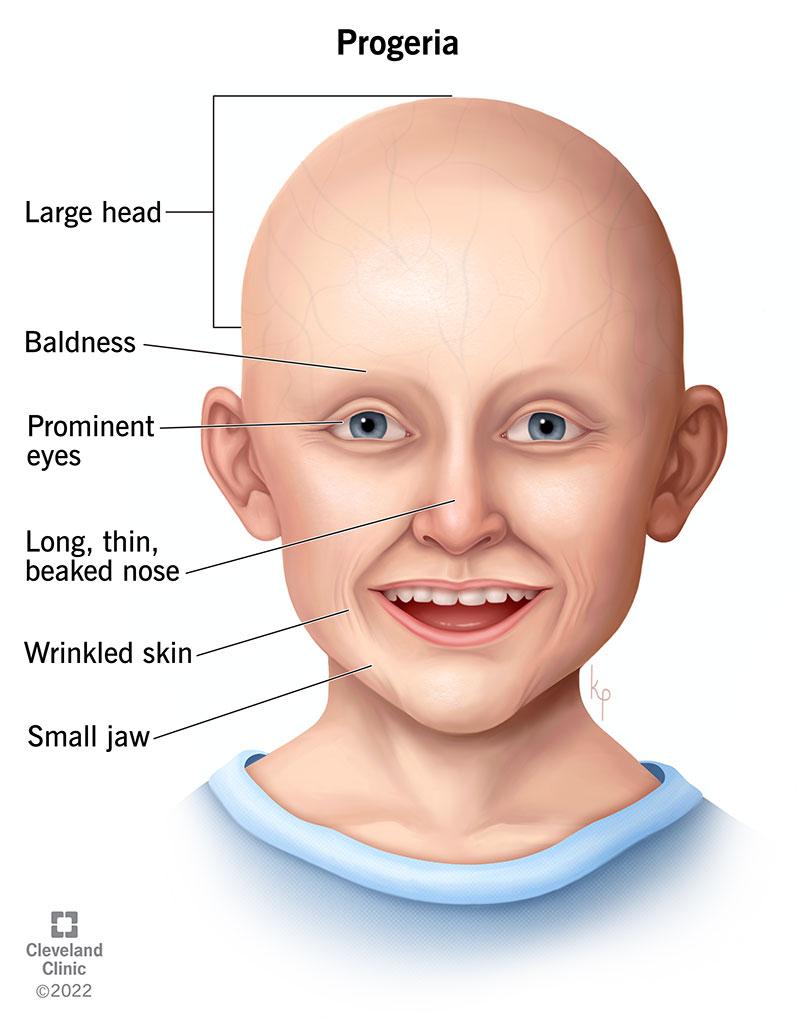

Progeria is an extremely rare genetic disease that causes rapid aging in children. Newborns with the disorder appear to be healthy at birth but usually start to show signs of premature aging during their first one to two years of life. Their growth rate slows and they don’t gain weight as expected. Children with the condition have typical intelligence. However, their rapid aging causes distinct physical characteristics, including:

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Progeria gets its name from the Greek word “geras,” which means, “old age.” The classic type of progeria is called Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, or HGPS. Dr. Jonathan Hutchinson and Dr. Hastings Gilford originally described the disease in the late 1800s.

Progeria is always fatal. The average age of death is 14.5 years, although some adults with progeria will live into their early 20s. A drug called lonafarnib has been shown to slow down the progression of the disease.

Death most often occurs as a result of complications of severe atherosclerosis. This is the same heart disease that affects millions of typically aging adults but at a much younger age. Atherosclerosis occurs when plaque builds up within the walls of your arteries. This makes them less elastic and therefore, stiffer. Complications can lead to heart attack or stroke.

Progeria is a rare genetic condition that can affect anyone. It most often occurs as a result of a new (de novo) genetic mutation. This means there’s no biological family history of the disorder.

Advertisement

Progeria is extremely rare. It occurs in 1 in every 4 million live births worldwide. About 400 children and young adults around the world currently live with progeria.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://my.clevelandclinic.org/-/scassets/images/org/health/articles/17850-progeria)

Progeria symptoms look like the signs of normal aging in human beings, but they occur at a much younger age. Starting within the first two years of life, children with progeria begin to show signs and symptoms of rapid aging that include:

Craniofacial abnormalities may include:

As the condition advances, less obvious symptoms may begin to develop. These include:

A genetic mutation in the LMNA gene causes progeria. The LMNA gene is responsible for making a protein called lamin A.

Lamin A is an important part of the structural scaffolding that holds the nucleus of each cell in your body together.

A tiny mutation in the LMNA gene causes it to create an irregular form of the lamin A protein called progerin. Progerin takes the place of the lamin A and makes the nuclei of your cells unstable, slowly damaging them. This leads to the early death of every cell in your body, which causes the process of premature aging.

Almost all cases of progeria occur as a new, spontaneous (de novo) mutation in the LMNA gene. This means there’s no biological family history of the disease. It isn’t inherited from a parent. The mutation nearly always occurs in the sperm cell before conception.

Progeria is an autosomal dominant disorder. This means one copy of the mutated gene in each cell is enough to cause the condition.

Your child’s healthcare provider may be able to diagnose your child’s condition based on their physical appearance. They’ll perform a physical exam and ask about your child’s symptoms. If they suspect progeria, they can use genetic testing to confirm the diagnosis. The test requires taking a blood sample from your child.

There’s currently no cure for progeria, but researchers are studying several drugs to treat the condition. Progeria treatment includes the use of a drug called lonafarnib (Zokinvy™). Originally developed to treat cancer, lonafarnib has been shown to improve many aspects of progeria. The drug has increased the average survival rate of children with the disease by two-and-a-half years. Every child on the drug has shown improvement in one or more of four areas:

Advertisement

Physical therapy may help your child achieve a good range of motion, balance and posture. In addition, it can help reduce pain in their hips and feet. Occupational therapy can help your child develop in areas such as eating, personal hygiene and handwriting.

Your child may benefit greatly from care to help them live as healthy and comfortable a life as possible. Your child’s healthcare provider will monitor and manage their condition through:

Advertisement

Your child needs adequate nutrition to grow. They may need supplemental nutrition (including a feeding tube). Keeping your child well-hydrated can help reduce the risk of sudden neurological problems. Talk to your child’s provider about healthy ways to encourage your child to get enough calories and hydration.

Progeria is a fatal condition that causes early death. The average life expectancy of a person with progeria is 14.5 years. However, some children die as young as 6 years old, and some adults with progeria live into their early 20s.

Death typically occurs as a result of complications from atherosclerosis. More than 80% of deaths are due to heart failure and/or heart attack. Treatment with the drug lonafarnib has shown promising results and has extended the life of people with progeria by two-and-a-half years.

An extremely rare genetic change causes progeria and it usually doesn’t run in families. The overall odds of having a child with progeria are about 1 in 4 million. However, once you have a child with progeria, there’s a 2% to 3% higher chance of having another child with it. That’s because of a condition called mosaicism. With mosaicism, a small proportion of a parent’s cells carry the genetic mutation for progeria, but the parent doesn’t have the disease. If your child has progeria, you may want to consider genetic testing to learn about your chances of having another child with the disease.

Advertisement

You can’t prevent progeria because it’s a very rare genetic condition. The condition happens most often due to a new genetic mutation, which means it happens randomly. The condition typically doesn’t run in families, which makes it difficult to predict. However, if you have one child with progeria, your chances of having another child with the disease increase slightly. You may want to consider genetic testing to learn about your risks.

If your child has progeria, you should try to create as normal a home life as possible. Try to include your child in as many activities as possible, but be sure not to let other children in your family feel overlooked.

Be honest but age-appropriate with the entire family when discussing the fact that your child with progeria will only live to a certain age. Counseling sessions may be helpful at various times.

Also, talk to your child about the fact that some people will be taken aback by seeing them. Discuss how your child should respond to stares and whispers.

Many children with progeria attend school. They usually need accommodations to allow them to fully participate and be comfortable and safe. You should meet regularly with your child’s school administrators, nurses, therapists and teachers. That way, everyone can work together to meet your child’s needs. This includes creating and sharing a plan for how to get your child emergency care if needed at school (such as for sudden shortness of breath or chest pain).

In addition to Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, several other conditions cause premature aging. These are called progeroid syndromes. Neonatal progeria, or neonatal progeroid syndrome, is one of these conditions. Also known as Wiedemann-Rautenstrauch syndrome, this disease causes growth delays and wrinkled skin. However, neonatal progeroid syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. This means both copies of the mutated gene in each cell need to be passed on to cause the disorder.

Finding out your child has progeria can feel overwhelming and confusing. Your child’s healthcare provider will support you and your family as you cope with their diagnosis. Your child’s provider can also help you understand possible treatment options that can slow down the progression of the disease. Many parents of children with genetic conditions such as progeria find support groups helpful. Asking questions and learning about the experiences of other families can be comforting and remind you you’re not alone.

Sign up for our Health Essentials emails for expert guidance on nutrition, fitness, sleep, skin care and more.

Learn more about the Health Library and our editorial process.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

Cleveland Clinic’s health articles are based on evidence-backed information and review by medical professionals to ensure accuracy, reliability and up-to-date clinical standards.

As your child grows, you need healthcare providers by your side to guide you through each step. Cleveland Clinic Children’s is there with care you can trust.