“It can’t be Parkinson’s … can it?”

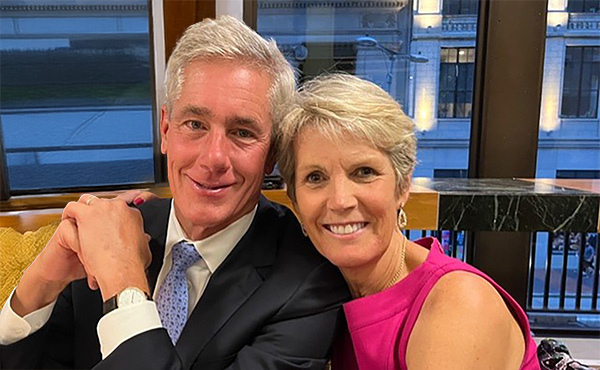

“I remember my husband and I were together in the elevator going up to the doctor's office,” says Sally Terrell. “And I remember thinking it can't be Parkinson's, but what else could it be? I was kind of in denial. But I think some part of me knew that's what it was.”

Sally was 46 years old when she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2004. Her symptoms began as a slight tremor in her right pinky finger, which she noticed one night while she was reading in bed. She called her primary care doctor, who took one look at her and recommended that she see a neurologist. At that point, Sally recalls, it was only her right hand and just a few fingers would be tremoring.

Sally and her husband, Steve, are parents to three children, the youngest of whom was a senior in high school at the time. Married now for 45 years with 11 grandchildren, back then Sally and Steve were beginning to think about life as empty nesters and how they might spend their time together.

“We told our children right away; they handled it pretty well. They were sad. They certainly have been supportive for all these 21 years,” says Sally. “I think it was hardest on my parents. My father tried to explain it away, saying, ‘Oh, well I can shake too. Everybody shakes a little bit.’ I think they wanted to be in denial for a while. That was one of the hardest things.”

Learning to Push Her Limits

The first few years following her diagnosis were spent with various doctors, who had differing opinions and treatment plans. Medication helped to control her symptoms but because disease symptoms can vary from person to person, it can take time to find the correct medication or combination of medications that is most effective.

Then in 2009, Sally’s uncle, Jim Biggar, a Trustee of Cleveland Clinic, told her about a new clinical trial at Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute, led by Jay Alberts, PhD, now the Vice Chair of Innovation at the Neurological Institute and holder of the Edward F. and Barbara A. Bell Family Endowed Chair.

Always proactive about her treatment, Sally eagerly joined Dr. Alberts’s trial, which focused on the effects of forced exercise on patients with PD. Three days a week, participants would ride a recumbent bicycle for 45 minutes at a forced pace. The concept of ‘exercise is medicine’ for PD is supported by evidence that regular exercise may delay the onset of PD symptoms and can improve motor scores, balance and quality of gait in those with the disease.

“Exercise really did help the symptoms,” says Sally, even though hers were still mild. “When the medication wore off they would get worse, but it was still manageable.”

Today, Sally is more active than ever. She learned in the clinical trial that any exercise that stretches her and pushes her limits is good for her. In addition to twice weekly workouts with a personal trainer, Sally tries to do something every day, whether it's taking a long walk or playing golf, pickleball or paddle tennis. “I have to pinch myself sometimes because I know that I could be in a wheelchair. I am so fortunate,” she says, with a catch in her voice.

Good Fortune is Her Reminder

Sally says having PD has made her very compassionate toward people who have it much worse than she does. “Whether it's Parkinson's or multiple other diseases, it's made me empathetic.”

She also feels fortunate because the external symptoms have not progressed to where strangers can tell that she has PD. “If you saw me today, you would not know that I have Parkinson's unless I told you. And that's a good thing – I am able to hide it pretty well. If my leg is shaking, I switch my legs. If my arms are, I hold my arms. For the most part I haven't had any gait problems. I'm able to play any sport I want. And so outwardly, I've been very fortunate,” she says.

However, Sally has many of the internal side effects and symptoms that occur with changes in the brain and body, such as constipation, sleep disturbances and night terrors, fatigue, restless legs and heightened emotions.

A few years ago, she had terrible back pain and needed surgery. “Before the surgery, I couldn't walk for three months,” she says. “I was crawling or bent over or in a wheelchair and it just sent my Parkinson's out the window. It was terrible. I had dyskinesia – I couldn't control that.”

Sally is grateful that she regained her strength following the surgery as severe trauma can impact the progression of PD. She says she’s accepted her diagnosis and tries not to think about it too often. “Sometimes I get a little concerned because I've had it so good for so long and I think I'm due for it to take a turn. It is always a good reminder to me that I'm not in control of my life.”

Advocating for Innovation

“I love the people who work at Cleveland Clinic because they care,” Sally says. “Those who have helped me in neurology are some of the dearest people I know. I've known them for so many years because they're still there and I'm still here.”

Since 2019, Sally has been a member of the Neurological Institute’s Advisory Committee, which serves to increase the institute’s visibility and reputation while helping to secure philanthropic sources to advance neurological innovation, discovery and patient care. While she was drawn to the committee because of the advocacy opportunities, she and Steve also provide support because, as she puts it, “I want to keep the Cleveland Clinic the best source of help that I can get.”

Cleveland Clinic Brain Study

When Sally and Steve learned about the Cleveland Clinic Brain Study, they were immediately intrigued. “I think medicine in general seems to be reactive and diagnostic,” she says. “It would be better if we, as a culture, were looking out to prevent things before we get sick—if we were able to prevent and look ahead and see who will get these diseases. Can we someday preempt brain changes by watching it age in the regular population? It's a simple but brilliant idea.”

Her hopes for the 20-year study include a better understanding of the brain and diseases like PD and Alzheimer’s disease. “With the technology we have today, it seems that just looking at a large sample over time would show glaring evidence that some things change before we’re aware. In Parkinson's, for example, it’s said that you have it for eight years before you know it.”

Sally and Steve’s understanding of the need for support for brain research led them to make a $100,000 gift to the study, which is 100% funded by philanthropy. “We feel very blessed that we can hopefully help others. I can't make people well, but I can help fund brain research by giving to a place like Cleveland Clinic where it's well-used and appreciated and so many patients will benefit,” Sally shares.

When she thinks about the future, Sally’s feelings are a mix of optimism and stoicism. “I have to appreciate every day I have and every day that I'm able to help others with Parkinson's, encouraging them to get out and get exercise and see a doctor,” she says. “I always say that the three things that helped me were the medication, exercise and the power of prayer.”

3D-Printed Simulators Enhance Educational Programs

A fifth-year neurosurgery resident at Cleveland Clinic is enhancing the program experience one 3D print at a time. Robert (Bob) Winkelman, MD, saw an opportunity to create low-cost spine and cranial surgical simulators using a 3D printer. Now, with the help of a Catalyst Grant, he is able to produce enough models for monthly learning sessions with his colleagues.

“In these sessions, residents can look at the spine, rotate it and appreciate the anatomical relationships,” says Dr. Winkelman. “That would be challenging with a cadaver.” Although training in the cadaver lab is certainly essential, it has its limits when it comes to feasibility. “The cadaver program is an amazing resource, but it's not practical for us to get the quantity we would need on a regular basis,” says Dr. Winkelman.

Commercially produced surgical simulators are an option, but their high cost and long acquisition times make them difficult to use regularly in residency programs. “Once you have put the screws and instrumentation in a commercial lumbar spine simulator, you’ve expended that simulator,” says Dr. Winkelman.

The sessions with the 3D-printed models allow trainees to make mistakes and learn from them in a consequence-free environment. They are also working on these dedicated skills in an open operating room where neurosurgery faculty, like William Clifton, MD, who is Dr. Winkelman’s Catalyst Grant co-recipient, provide invaluable knowledge.

“I think it’s pretty powerful that residents are rehearsing what they will be doing in the same setting with the same tools in which they will be doing it,” says Dr. Winkelman. “But the stakes are non-existent because it's a plastic model versus a human being.”

Catalyst Grants are funded annually by thousands of gifts of all sizes from donors. The competitive grants are awarded to caregivers with ideas to improve the lives of Cleveland Clinic patients, the organization and communities around the world. Dr. Winkelman was awarded $25,000.

“Cleveland Clinic is just a special place to train,” says Dr. Winkelman. “I'm just very grateful to have received the Catalyst Grant and been selected from many ideas. I am very appreciative of people being willing to make that investment.”

Dr. Winkelman's use of 3D printing technology is transforming the neurosurgery residency program at Cleveland Clinic and setting a precedent for other specialties. This initiative is paving the way for a future where surgical simulators are readily available, affordable and tailored to the needs of trainees, ultimately better preparing surgeons to provide quality care.

Cleveland Clinic and Community Partners Celebrate Lead Safe Achievement

Lead poisoning poses a significant threat to children under six, with Cleveland's children bearing the brunt of this crisis at a rate four times the national average. The city’s aging housing stock – with nearly 90% of homes built before the 1978 lead-based paint ban – is a significant contributor to this heightened risk.

Alongside community partners, Cleveland Clinic recently participated in a ribbon-cutting ceremony in Cleveland’s Old Brooklyn neighborhood to celebrate one of the first providers to achieve lead-safe clearance through the Lead Safe Child Care pilot program. The program is an expansion of Cleveland Clinic's commitment to addressing lead poisoning in the community. This program is an organizational community priority.

Lead exposure, even in the smallest amounts, is harmful. Children often ingest lead through paint chips or dust near windows and floorboards. The neurotoxin wreaks havoc on the brain and nervous system, impeding growth and development, and causing learning and behavioral issues. The irreversible nature of lead poisoning underscores the critical need for early screening and prevention.

In 2019, the City of Cleveland joined hands with families impacted by lead and local organizations, including Cleveland Clinic, to form the Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition, a robust network of over 500 members across 150 organizations. The coalition successfully advocated for the Lead Safe ordinance, mandating all rental properties built before 1978 to be certified as lead safe. Cleveland Clinic pledged $52.5 million to support the coalition's efforts.

Building on this momentum, the City of Cleveland, Cleveland Clinic, Lead Safe Cleveland Coalition and Starting Point collaborated in 2024 to create a national model to combat lead poisoning in early childhood settings. The Lead Safe Child Care pilot program offers vital resources and construction assistance to remediate harmful lead hazards from a test group of childcare centers and home-based providers.

To date, the pilot has supported remediation efforts at four licensed childcare sites, creating healthier conditions for 144 youth. Fifteen more projects are underway, with a total of 30 set for completion by the end of 2025. Once finished, the initiative will protect 703 children from lead exposure – an important step in Cleveland’s mission to provide every child a safe place to grow and prosper.